‘‘My father always told me: in Sohag, the moment you open the door, nature greets you,’’ says Gehad Abdalla, an Egyptian artist originally from Sohag. ‘‘Everything we create comes from nature. It’s in our craft, in our hands, and pieces of it now sit in places like the British Museum and the Met in New York.’’

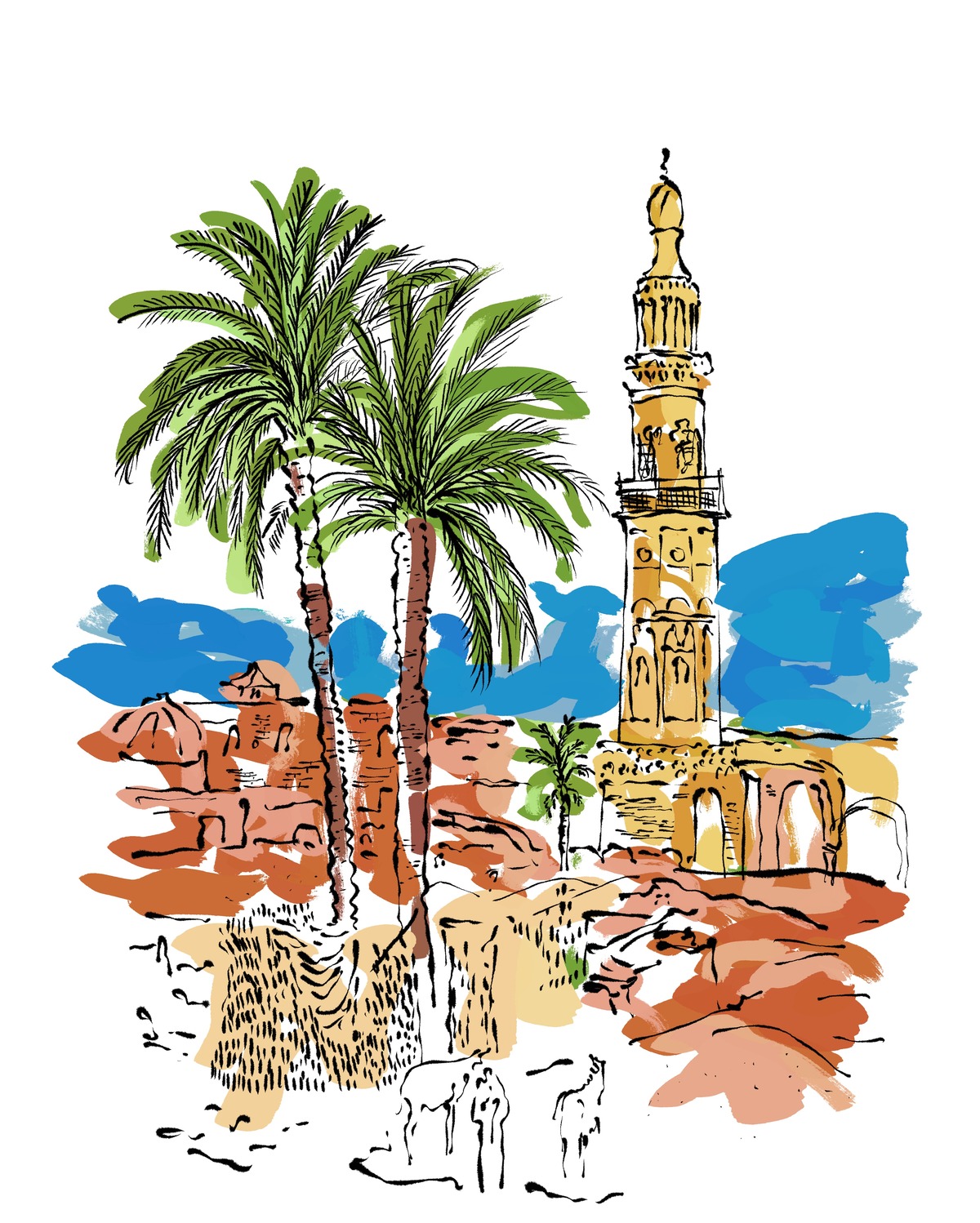

In Sohag, nature is not the neatly trimmed trees that city dwellers know. It is not organized into tidy lines or curated like an exhibition. It is raw, real, and authentic, like clouds drifting across the sky, forming shapes one could try to recognize but never fully can. Nature, in Sohag, resists being tamed, refuses to be forced into human order, and instead compels one to wrestle with it, to try and understand it on its own terms.

The mountains in Sohag never shy away from their rough edges or their untamed lines. The Nile continues to carry ancient stories, told from one generation to the next. History in Sohag is bound together in the same way the river flows, without pause and without end. In Sohag, history preserves inscriptions, songs, dances, tales of the hunt, and the daily life of agriculture, all rooted in the ancient city of Akhmim in the northeast of Sohag.

These traditions are passed from one person to the next kept alive and guarded, which is why they run through the work of artists like Gehad. Now the owner of her own design studio in Australia and a design graduate at the University of Western Australia (UWA), she carries these traditions and the soul of Sohag within her practice.

From tracing the flowing lines of trees, rivers, flowers, palm trees, animals, and birds in all their forms, to capturing the traditions of dance and song, Gehad’s work strives to authentically portray the lives of her family and ancestors, even though she did not grow up in Sohag. Raised in Alexandria, she still carries Sai’di culture deeply within her, so deeply that where one grows up becomes secondary. The culture endures, passed down from one generation to the next.

Trained as an architect, Gehad’s path into art and design unfolded almost by chance rather than by intention. Though she had always sketched, it was only last year that she began to treat it as a career, sharing her work publicly through Instagram.

“My passion has always been for mystery, for stories, for heritage,” she explains. “When I sketch, it isn’t only about recreating a scene, it’s about feeling the memories and emotions behind it.”

Seeing Egypt beyond Tutankhamun

Egypt has long leaned on Tutankhamun to tell its story; the world has come to know Egypt through the pharaohs and the ancient Egyptian civilization. Yet they are not the only voices carrying its history. Across time, it has also been modern Egyptians living in humble villages, who have held the weight of their own traditions, preserving and passing them forward on their shoulders.

For Gehad, being from Sohag meant living inside a culture that most outsiders, and even many Egyptians, rarely see. Living abroad has only sharpened her sense of identity, recognizing that many foreigners carry assumptions and misconceptions around what it means to be Egyptian, often reducing it to a connection with ancient Egypt while overlooking the realities of modern Egypt.

“When you live outside your country, especially in a non-Arab culture, you think about your identity much more. It’s very easy to face subtle exclusion. So it’s important to embrace your identity fully, like, ‘this is me, this is my whole package, I’m not going to hide it,’” she says.

Embracing the whole package of her identity, however, is rarely simple. In Australia, for instance, she often finds herself boxed into stereotypes. “Here, they love putting you in a category: ‘Oh, you’re Egyptian, so you must draw the Pharaohs.’ Even in art school, a lot of assignments were like: draw something about ancient Egypt.”

At the heart of her practice lies the process of reclaiming her identity: stepping outside Western narratives, resisting Orientalist tropes, and distinguishing between the monumental Egypt of pyramids and pharaohs and the lived Egypt of villages, traditions, and Sa‘idi culture.

“When I lived in Alexandria, I wasn’t aware of the cultural differences. But when I think about it now, my grandfather wore Sa‘idi clothes his whole life. I thought that was normal. I ate Sa‘idi food every day,” she says.

“My grandfather spoke in Sa‘idi accent, my uncles still use proverbs and expressions from Upper Egypt. Even in cooking, we have our own recipes, such as the bamya weka, which is okra cut up and cooked in broth until it’s like molokhia with meat.”

She also became aware of how cultural understanding is shaped by the disconnect between media representation and everyday life, with mainstream narratives frequently casting Sa‘idi culture as backward or traditional, while erasing its nuances and individuality.

“I grew up watching Sa‘idi TV series, like Al Do’ El Shared (The Stray Light, 1998). My grandfather would watch and comment, ‘that’s not accurate. In Upper Egypt, we dress like this, we eat like this.’ The media often shows Upper Egypt as a place where women are oppressed, or where it’s only violent,” she adds.

“But that’s not the full picture. My grandmother had her own shop, worked in trade. There are always these other narratives that don’t make it to the mainstream.”

For Gehad, Upper Egypt is far from a closed world; it has always been outward-looking, full of nuances that are too often overlooked.

“My father’s family worked hard, traveled the world, spoke other languages. Some Upper Egyptians are actually very open. Tourism in Luxor and Aswan exposed them to the world. I’d even say Upper Egyptians are more cosmopolitan than others, but they carry a strong sense of pride and hospitality.”

That pride, she adds, comes from the land itself. “In Upper Egypt, the mountains and the tough environment shape people. They’re strong, but also generous. The houses are far apart, so if someone visits, you want them to stay a whole week.”

Rooted in stories, translated into art

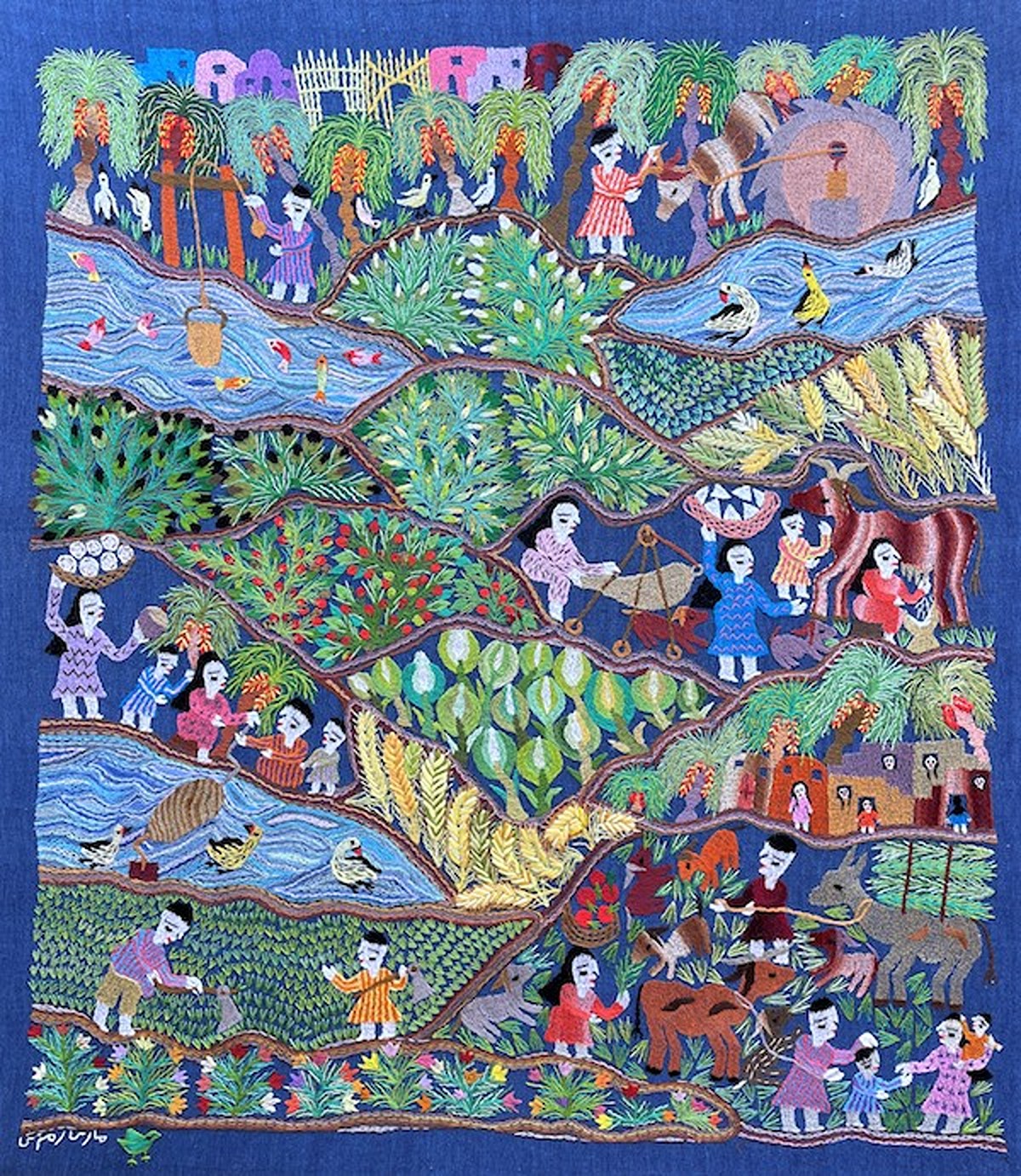

Egyptian women have long been the brain and the creative force behind many of the visual designs that shape the country’s identity. The textile industry alone employs more than 2.5 million workers, half of whom are women.

For Gehad, this lineage is what draws her closer to translating her own home into art. In Sohag, the village of Akhmim has stood for centuries as a center of textile craft, famous for its finely woven wool and linen.

These textiles carried with them legacies of women’s creativity, a visual language passed down from generation to generation. Their designs resist rigidity or templates, instead guided by simplicity, daily life, and tradition, with each piece a reflection of how culture breathes in the everyday.

“Living in that world, for me, was like living in a capsule,” Gehad recalls. “Eighteen years of listening to stories, songs, proverbs. My siblings taught me Sa‘idi poetry when I was just four years old. All of this was my world, without me even questioning it. Only when I left, I started asking: Why are we like this?”

Around five years ago, after moving to Australia, the differences became clearer, and she found herself paying closer attention to her identity, driven by a deeper urge to reflect her culture with authenticity and to translate it visually.

“Women, especially Sa‘idi women, shaped so much of Egypt’s visual culture. The patterns you see in museums in London or New York, many came from villages in Sohag.”

She often returns to Akhmim, a town in Sohag famous for its ancient textiles. “If you look at the textiles and you look closely at the details, you’ll see that they are drawn from palms, beans, and the everyday environment. For me, that connection between women, land, and craft is exceptional.”

Her nostalgia, she explains, is not just for places she knew, but also for those she only inherited through stories.

“I miss Egypt terribly, even the places I’ve never seen. That’s what I try to translate into my work. To show that Egypt is not just Cairo. That Upper Egypt, Sohag, the villages, all of it is Egypt too.”

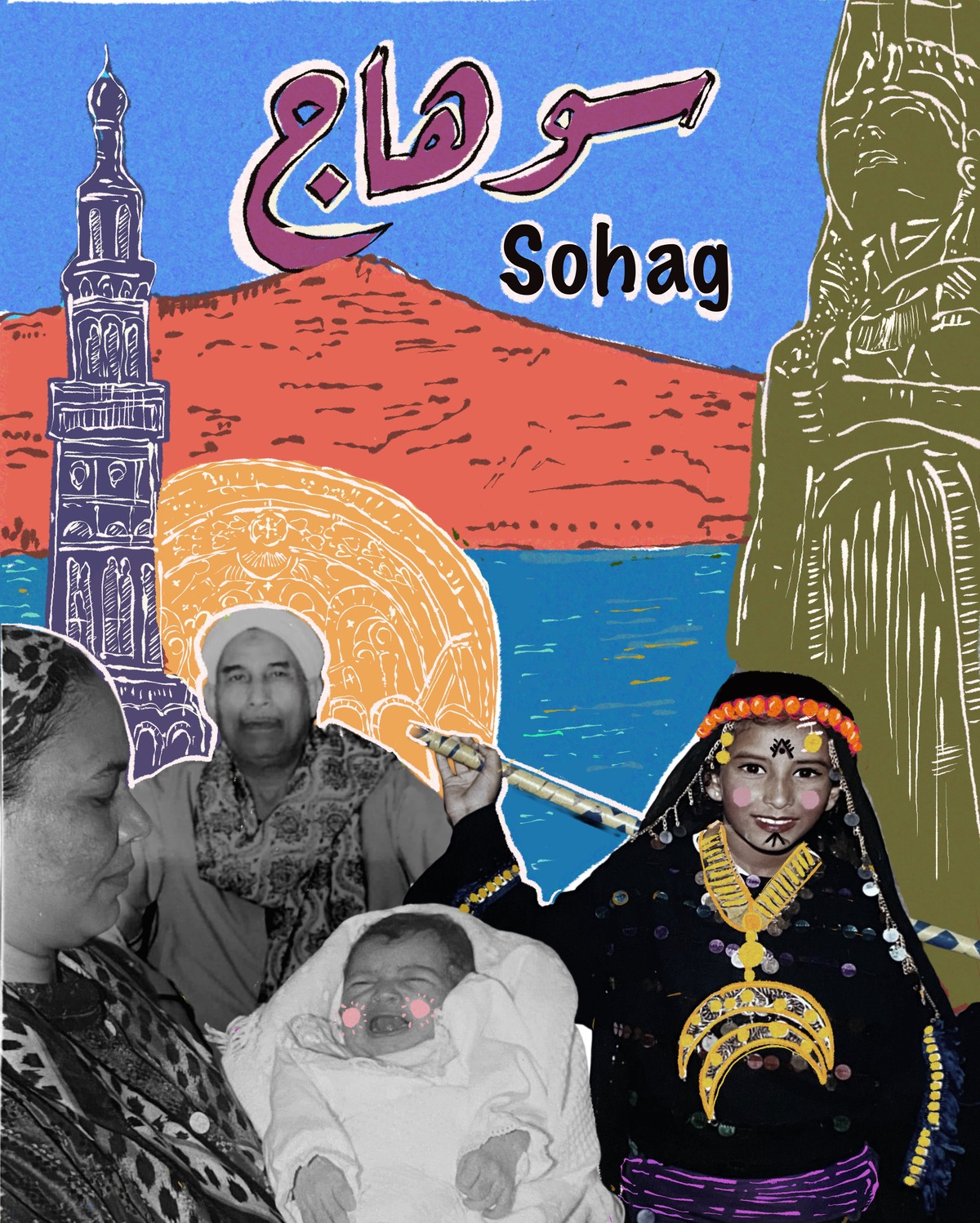

Gehad’s artistic language, over time, became a fusion of memory and reinterpretation. She has explored collage, painting, ink, mixed media, and recently shifted from traditional to digital art.

Her style has always been rooted in culture, heritage, and storytelling, and during her time at UWA’s design school, she developed more experimental techniques, such as layering textures, playing with bold compositions, and always starting with raw sketches.

“In my artworks about Sohag, I try to represent it through colors and illustrations from the stories I was told, such as blue for the Nile, green for crops, and earthy colors for mountains. Sometimes my sketches are also about feelings, such as how I see the mountains, the desert, and the everyday moments,” she adds.

One of the most valuable lessons she has gained as a design student in Australia is learning how to break down her ideas and refine them until they become a single, clear symbol, free of confusion or excess.

“When I came to Australia, one of my professors pushed me to strip things down, and to translate my idea into one line, one sentence, and one gesture,” she says.

“It completely changed me. In Egypt, we tend to overload our knowledge, our presentations, and even our sketches. Now, my journals are filled with icons instead of text. I started seeing culture in the smallest things.”

What remains constant since she first began sketching is her belief that art is a vessel for truthful representation. “It’s very hard to draw or represent a culture you don’t understand. It won’t come out authentic unless you truly see it differently. And I think that’s the role of artists everywhere, which is to translate what others overlook, to show the world in a new way.”

Her grandmother’s stories about daily life, and others were legends, have also shaped her as much as her education.

“She would always tell me the story of Isis and Osiris, the way Isis searched for Osiris’s body parts along the Nile, and from that came songs of mourning. It was told so dramatically, like a TV series. That story, and so many others, left their marks on me. I carry them into my art.”

Beyond organizing workshops within her community in Australia to raise awareness about Egyptian culture and its diversity, including one workshop titled “Draw Like an Egyptian,” Gehad now hopes to expand her design studio as a space to translate Egypt’s authentic story through artwork, carrying with it both history and storytelling.

“I carry my identity with me everywhere I go, and that shows up in my work,” she says. “I’m constantly thinking about home; the texture of Sohag homes, the rituals, the noise, the quiet. I try to capture those everyday moments that are full of emotion and meaning.”

Comment (1)

A heartfelt thank you to the Egyptian Streets team for this opportunity, for giving me the space to share this story so thoughtfully. A very special thank you to Mirna for her patience, for truly listening, and for capturing my story with such care. I really enjoyed our conversation; it felt less like an interview and more like sharing memories with a friend.