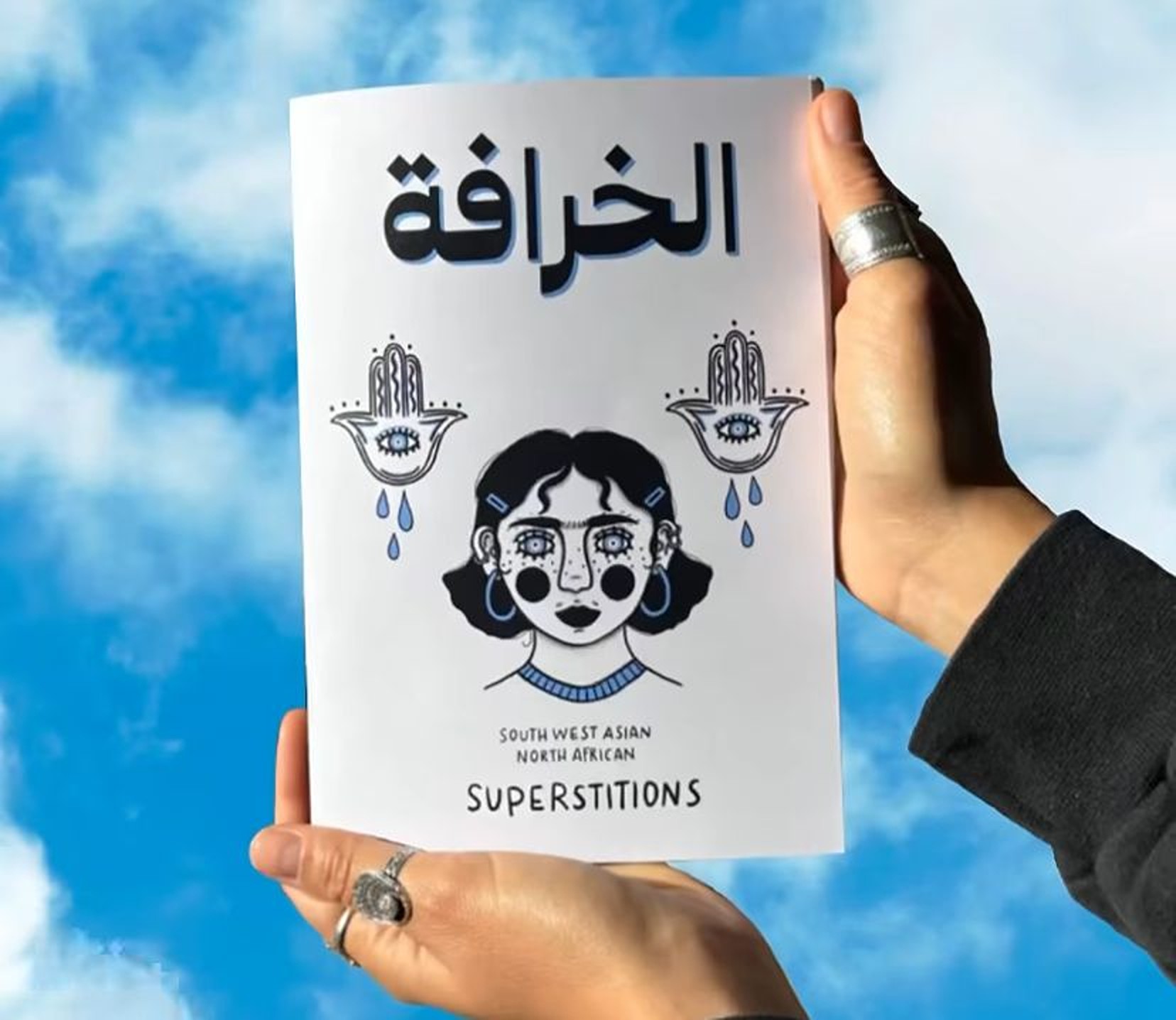

Teta, which means grandmother in Arabic, is often every Egyptian child’s first storyteller; the one who opens the door to a world where the past slips easily into the present, stretching time as if it were something she could hold. In her wrinkled hands, the same hands that once wrapped around ours as the gold bangles on her wrists chimed softly, she curated her own museum of Egypt. Through her words and vivid imagery, she preserved pieces of heritage that never make it into digital archives, and stories held not in galleries, but in a grandmother’s heart. Over the years, countless attempts have been made to preserve our heritage, from digital platforms and online museums to lectures, exhibitions, and fleeting physical installations that showcase Egypt’s or the Arab world’s past for a moment in time. But as soon as someone leaves the room or scrolls past the screen, that fragment of memory slips away again, disappearing just as quickly as it appeared. Yet a new generation of Egyptian creatives, like Dutch-Egyptian illustrator and storyteller Naomi Attia, is rethinking how heritage can endure. Through her illustrated zine, Al Khorafa (Superstitions),…