In late January 2011, Cairo sounded different. Chants rolled through Tahrir Square, repeated until their rhythms stuck in our heads. Cardboard signs were written, crossed out, and rewritten as events unfolded. Mobile phones were held high, recording fragments of history as they happened. Along nearby streets, walls filled quickly, names, faces, slogans, and drawings layered over one another, turning public space into a running record of the moment.

This was the early days of the uprising that began on 25 January 2011, when mass protests spread across Egypt and eventually led to the removal of former president Hosni Mubarak.

As political uncertainty grew, creative expression expanded alongside it. Songs, graffiti, satire, and videos moved with the demonstrations, helping people communicate, document, and make sense of what was happening around them.

More than a decade later, these moments still shape how the uprising is remembered, not only as a political rupture, but as a cultural one. Yet, this was not the first time culture filled the gaps left by political uncertainty.

When Culture Helped Egyptians Find a Voice in 1919

Nearly a century earlier, a similar dynamic unfolded during the 1919 Revolution against British occupation.

As formal political activity was tightly restricted, streets, cafés, theatres, and newspapers became spaces where political ideas could circulate more freely. Nationalist songs were performed publicly, theatrical productions embedded satire and critique of colonial rule, and popular publications helped carry these messages beyond elite circles.

A 2020 book published by Cambridge University Press notes that colloquial music, vaudeville-style theatre, and the popular press were among the most effective tools for mobilization during the uprising, allowing nationalist ideas to reach ordinary Egyptians at a time when direct political organizing faced severe limits.

Composer Sayed Darwish emerged as a defining cultural figure of the period. Writing in colloquial Arabic, his songs reflected a shared mood and circulated widely through live performances and gramophones. Works such as Bilady, Bilady, Bilady (My Country, My Country, My Country), composed in the early 1920s and later adopted as Egypt’s national anthem, became closely associated with the nationalist movement surrounding independence and mass mobilization.

According to the 2011 book ‘Ordinary Egyptians: Creating the Modern Nation Through Popular Culture’ by Ziad Fahmy, pop music played a key role in shaping a collective sense of national identity during the period, a legacy that continues to be examined by scholars today.

Culture, in moments like these, did not replace politics. It moved alongside it, a pattern that would resurface again in later periods of national crisis.

Echoes of Crisis in Music After 1967

That pattern re-emerged decades later, after the defeat of Arab forces in the Six-Day War of 1967 marked a deep rupture in Egypt’s modern history.

The loss reshaped political discourse and left a lasting emotional imprint on public life. In the months that followed, music became one of the ways Egyptians processed that shock, not as spectacle, but as a shared public language.

One of the Arab world’s most influential cultural figures, Umm Kulthum began a series of fundraising concerts across the Middle East and Europe in late 1967, directing proceeds toward Egypt’s war effort and military recovery.

These performances drew large audiences and raised significant sums, placing music at the centre of a broader national response to defeat. At a time when official rhetoric struggled to address public morale, her concerts offered spaces for collective gathering and continuity.

Alongside these state-sanctioned efforts, a different musical current took shape outside official channels.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, poet Ahmed Fouad Negm and composer-singer Sheikh Imam turned their collaboration toward sharply political themes. Setting Negm’s colloquial poetry, often critical of regime failures, corruption, and social inequality, to music, their songs circulated widely among students, workers, and leftist circles, despite being banned from state media.

A 2025 study published on dissenting voices of Cairo notes that, after the 1967 defeat, Ahmed Fouad Negm and Sheikh Imam’s collaborations became explicitly political, reworking popular poetry into songs that circulated widely outside state media and resonated with audiences seeking alternatives to official narratives.

As political space narrowed during these years and the years that followed, informal cultural channels increasingly became sites of expression rather than exceptions.

The Rise of Cassette Culture and Everyday Expression

By the 1970s and 1980s, the pressures that followed the 1967 defeat had become embedded in everyday life.

Economic strain, rapid urban growth, and limited access to formal cultural platforms shaped how many Egyptians encountered music and media.

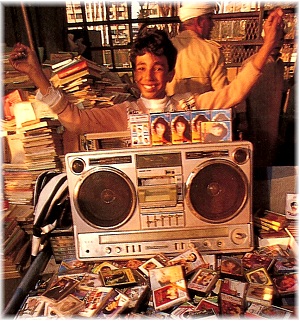

It was within this extended post-1967 context that audio cassettes quietly reshaped cultural circulation.

Cheap and easy to copy, cassettes made music faster to produce and harder to control. Songs no longer needed approval from state radio or official record labels; they could be recorded at home, sold by street vendors, and passed hand to hand, played in microbuses, cafés, and living rooms across the country.

A 2019 study published in the International Journal of Middle East Studies describes the cassette as a medium that decentralised cultural production, widening who could speak and who could be heard.

This shift helped fuel the rise of shaʿbi (popular) music, a working-class genre rooted in humour, frustration, and everyday experience, and performed in colloquial Egyptian Arabic.

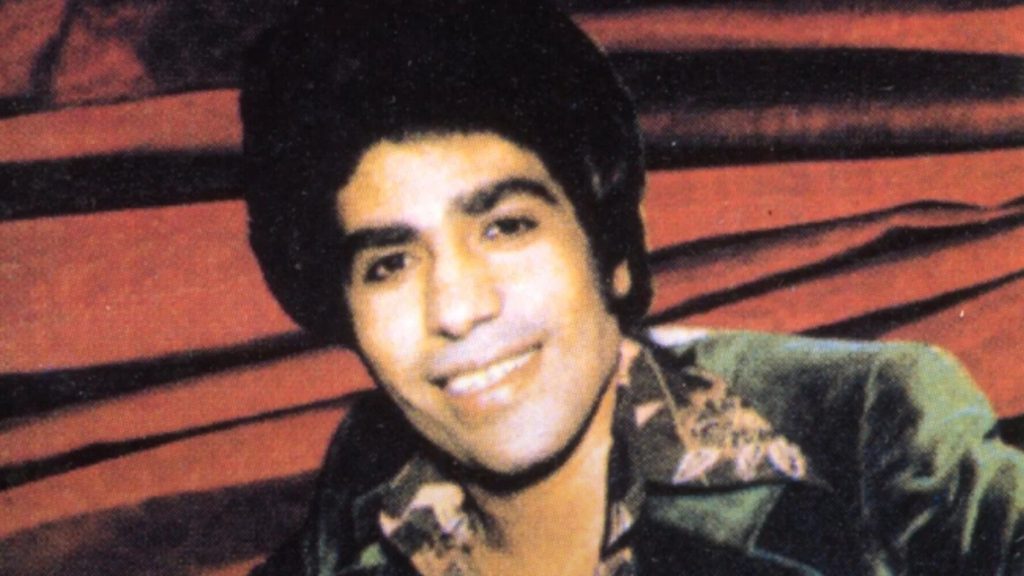

Artists such as Ahmed Adaweya gained popularity precisely because their music spoke to lived realities that were largely absent from official cultural platforms.

As with earlier moments in Egypt’s history, this expansion of expression did not emerge from abundance, but from limitation.

When access to formal channels narrowed or felt disconnected from public life, new spaces opened elsewhere. The cassette offered one such space, a pattern that would resurface decades later through digital media and the events of 2011.

Culture as Continuity, Not Exception

Across Egypt’s modern history, moments of rupture have repeatedly been accompanied by cultural expansion, not because crisis in itself is productive, but because culture offers a way to endure it.

From cafés and theatres in 1919, to songs after 1967, to cassette tapes circulating outside official media, and later to the streets and screens of 2011, cultural expression has functioned as a parallel language, one that documents, critiques, and carries emotional weight when official channels fall short.

These moments are often remembered as exceptional. In reality, they form a pattern. When political or economic systems narrow, culture widens. When official narratives harden, everyday expression multiplies.

This is not resilience as a slogan. It is practice, and it helps explain why, in Egypt, culture so often grows alongside crisis, not in spite of it.

Comments (0)