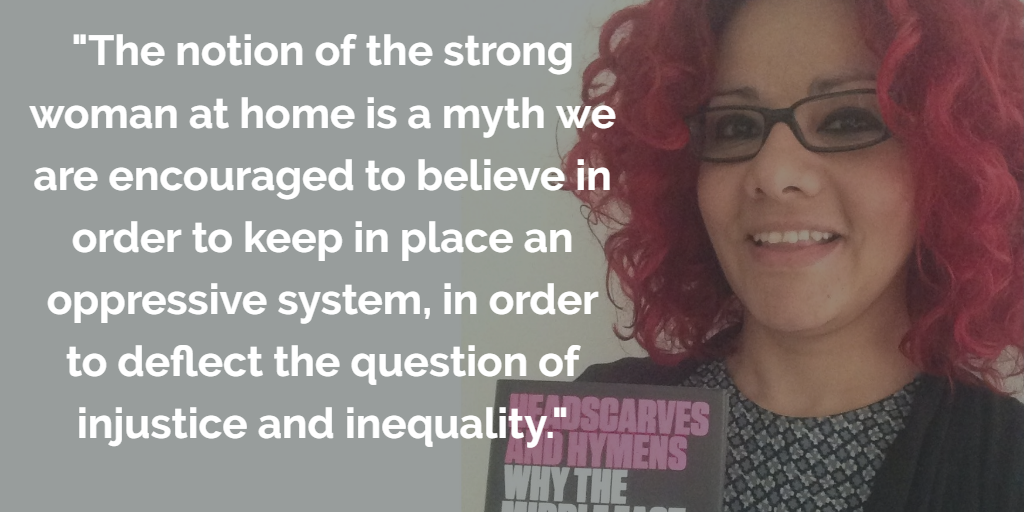

The last five words of Mona Eltahawy’s Headscarves and Hymens are “words say we are here”. Sure enough, her courageous words shout, from every page, raging against the oppression and subjugation of women of the Middle East.

Eltahawy broke with numerous societal taboos; she drew on the experiences of Latino and African-American women and their struggle for equality to bring into the open the full scale of the suffering endured by women in the Middle East. Eltahawy walks the talk and painfully recounts her own experiences at the receiving end of sexual molestation and violence by random men in Saudi Arabia, and Egypt, as well as by Egyptian authorities.

The book moves back and forth between Eltahawy’s rich personal experiences, the accounts of the many women she came into direct contact with, the various patriarchal religious teachings, and the legal and political realities of the region. Contrasting the personal narratives with the public must have been painful to write, yet it makes the writing more accessible. Certainly the words easy to read are completely out of order in a book of this sort; easy to follow and appreciate the extent of the suffering would be more appropriate.

The chapter titled ‘The God of Virginity’ dealt with the abhorrent practice of Female Genital Mutilation, or FGM. The chapter discussed the various forms of mutilation used across several countries, shedding light on the many countries where this practice is still carried out and tolerated with little knowledge or public debate. I was shocked to read that FGM had been practiced in Europe and the USA many years ago and, like Eltahawy observed, this does indeed offer hope that one day it will be possible for all young girls and women in the rest of the world to be spared from this destructive and cruel act.

Eltahawy also focused, appropriately, on what is known as Personal Status or Family Laws. In a systematic manner she showed that women in the entire Arab world suffer under unjust patriarchal laws that essentially reduce a woman to a mere child or even property. A highly accomplished and educated woman of 50 years in the UAE can not marry without the approval of her 19 year old son, and a husband in Lebanon can murder his wife with police and rescue workers unable to stop him to save her life so as not to violate the man’s right to private family matters.

Eltahawy debunked the various arguments that are used to defend the use of religious laws to govern family matters by demonstrating how the various legislation chose misogynist interpretation of religions over other possible interpretations; ultimately religion is co-opted to advance patriarchy and misogyny at the expense of women.

Eltahawy took on the arguments of those who continue to defend the current laws: “I often hear fellow Muslims: ‘But this isn’t the fault of Islam. It is the fault of Muslims who abuse religion.’ Then they usually launch into how perfect everything would be if we practiced ‘the proper Islam.’ Never mind that the clerics in Lebanon who opposed the anti domestic violence bill fully believed they were advocating for the ‘proper Islam’ ….. Our best chance for pushing back against such idealized notions is to offer examples from the lived realities of girls and women. Those who hold on to the ideal will remind us over and over again that the Prophet’s’ last sermon emphasized love and respect for women. But has the teaching made its way into personal status laws”.

Needless to say, as we look at ISIS we can see them too claiming the mantle of “proper Islam”.

As an Egyptian American Muslim, like Eltahawy, I have repeated statements that women run the homes and while doing so, I often questioned if that was indeed the case. This was such a common saying that I now assume it was used to show that Egypt was not such a backward place after all; the kind of statement we use to improve our own self image in the west. I loved the head on challenge to this very fallacy from Eltahawy: “The notion of the strong woman at home is a myth we are encouraged to believe in order to keep in place an oppressive system, in order to deflect the question of injustice and inequality.”

Eltahawy highlighted the role of women in the Arab Spring and she explored in great detail how the successive governments in Egypt and elsewhere fought against women coming out on the streets to demand freedom. The sad reality, Eltahawy painstakingly demonstrated, is that while women were demonstrating against various tyrannical regimes, many of the men standing beside them were not ready for the women to be free. Many used the excuse of priority: bring down the regime first; issues like women’s freedom and equality would come later.

Eltahway claims that a revolution against oppressive regimes cannot be successful without a revolution for women’s rights. Sadly, I can find no historical examples that would support her assertion that political revolutions are not possible without women’s equality revolution. Indeed, the Western experience would suggest that freedoms for women often lag that of the society and the delay of women suffrage laws offer examples of such. Perhaps one can make a very different argument which is that a revolution to liberate women from the suffering at the hands of their of their families and societies is more pressing than political liberation and perhaps a more urgent and worthy cause.

Headscarves and Hymens is an important book. It challenges head on those in the West who failed to speak out on abuse of women in the Arab World, and it speaks against Western governments, particularly the USA, for staying silent on basic rights for women in Saudi Arabia. It also challenges those Western self-proclaiming liberals who patronizingly defend blatantly misogynist practices under the pretense of being tolerant and understanding of other cultures; Eltahawy doesn’t mince her words in pointing out their neo-orientalist attitudes and cultural relativism.

I hope that this book will be published in Arabic for this work is nothing but a mirror held close up to the Arab and Muslim societies of the Middle East, it contains a lot of ugliness stripped of its traditional defenses, the lived ugliness of many women whose words say they are here and they say no, enough is enough!

Comments (0)