The Suez Canal remains, in the imagination of the world, as one of the most fantastic works of engineering ever accomplished.

Who would have imagined that it was possible to unite two seas, so that large ships could cross from one to the other, shortening long distance trips circumnavigating all of Africa? It was a display of the human capacities in re-shaping the planet to meet our needs.

Frenchman Ferdinand de Lesseps, the man behind the project of the Suez Canal, was consecrated as a national hero in France, and received the Medal of the order of The Legion of Honour, the highest order of merit for military or civil accomplishments. The work on the canal was advertised as the great wonder it was, using a relatively novel technique at the time: photography.

Attesting the construction: photography

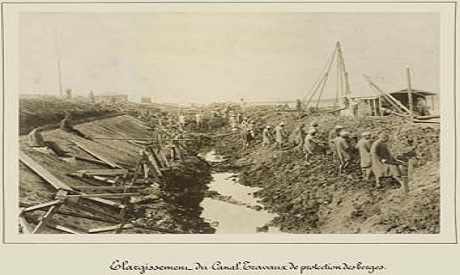

The process of the construction of both the Suez Canal and the Ismailiya Canal, much less advertised but also planned by French engineers, was documented intensely.

These photographs, however, were more than just photographs, they were charged with ideology and had a purpose. They represented, with feasible proof, the ideas of progress and technological development, as well as to publicize the project to investors and to show the monumentality of the task, and the technology that was used for it.

The Suez Canal Company, as well as independent photographers like Hippolyte Arnoux and Justin Kozlowski, produced a large quantity of such images, most of them depicting the (at the time) modern dredgers and other machines.

Some of the machines were floating, lonely while at work; it was these pictures that were also sold to travelers as souvenirs, and exhibited in World Fairs as it happened, for example, in Paris in 1889.

PhD candidate at New Jersey Institute of Technology, Mohamed Gamal El-Din, who was invited to the Annual History Seminar organized by the American University in Cairo to talk about his research, had been interested in the urban history of Suez from the perspective of the laborers.

The more he searched, the more a very significant fact became obvious: the laborers had been excluded from the photographic archives.

The pictures of the construction of the canal were made and distributed so profusely as to appear today in numerous archives, libraries and private collections all around the globe. The pattern was always repeated: machines only, no humans, except for some European expatriates. Where were the workers?

Gamal el-Din concludes that these images were the evidence of the “European Military and economic expansion” over the orient, citing scholar Leonard Koos.

The photographs were a vivid picture of colonialism, explaining, modifying and controlling the landscape of Egypt, and confirming the centrality of Europeans and their technology, over those who were less developed.

Pictures of laborers are almost non-existent, but the same peasantry was always depicted as part of an Orientalized Fantasia. Exotic, romantic, strange, and easy to tame. The public was hungry for reality, but the camera took only one frame of that reality, one can always choose what to frame, and what to leave behind. How did the workers fare?

The French-controlled Suez company was clearly in debt and would be unable to finish the works in the Canal in time, so they pressured the viceroy Sa’id Pasha, and Khedive Ismail to provide and pay for thousands and thousands of workers as an agreement with Lesseps in 1858.

The reports indicate that in 1862 there were 55,834 men and boys living in provisional shelters made of tamarisk leaves, overcrowded, with a total number of 120,933 between 1861 and 1862.

An Anglican Missionary, George Percy Badger confirmed the number of workers in the thousands and testified that they had been promised payment but now had lost hope on this happening, being forced to work and wanting to go back to their homes.

The reality of the workers in the Canal was dreadful. ‘Le Chantier du Canal de Suez’ (1859-1869) by Nathalie Montel showed that the workers didn´t even have enough to drink under the scorching sun and that there were two different kinds of life around the Canal. On one side there were banks, bakeries, and bars for the expatriates, and on the other side the misery and starvation of forced labor.

‘The Suez Canal… An Epic story of a People and the Dream of Generations,’ published by the Ministry of Education in 2014, claims that overall there were 1 million Egyptians employed in the construction, and around 100,000 died from 1859 to 1869.

The records of the Alexandrian Library show that the most common diseases were dysentery, smallpox, tuberculosis, hepatitis, and cholera, the latter being so deadly that in 1865 there were not enough men to carry the corpses. Forced Labor in the Digging of the Suez Canal, another book on the subject by the Egyptian Abdelaziz Al Shennawi showed how most of the work was done by hand.

The only evidence of these workers in the archives of the company is the plans for simple shelters to accommodate them, using structures that were easy to assemble and dissemble. But there is no trace of them, they were too primitive to be photographed, and to be part of the idea of development and progress they wanted to sell.

New times, new workers: history repeats itself

But this story is not uncommon, even recently, reports of Indian workers forced to live in unhealthy conditions in Dubai have come to light, and sometimes even compared with slavery. Many unregistered agents take these workers in obscure conditions, retaining their passports, forcing them to live in overcrowded spaces and sometimes lacking basic sanitary services. That is not the Dubai we all know for its wonderful and modern architecture, and obviously not the official image that the government tries to show the public.

When I asked about the New Suez Canal, Gamal El-Din agreed that the project was also being displayed as one in which technology championed over human labor. Coins, commercials and banners, as well as the campaigns in which people could invest with as little as one Egyptian pound also made the New Suez Canal a project “of nation building in a post-revolution era” he said, and one in which laborers were not present.

The stories of today’s Egyptian laborers might not be as terrifying as those of laborers in the first canal, but the stories of these laborers are still to be written too.

This research on the Suez Canal is only a small part of a wider effort of Gamal al-Din to show the story as it was not told. He is trying to give a voice to those who were systematically excluded from history, to form a larger picture of employees, the places where they worked and where they lived during the nineteenth century, and how they ended up shaping the modern cities we know today.

However, his views on labor are key to understanding labor today, and how, after much work of syndicates and labor rights unions, laborers are still neglected one way or another, not just in the Middle East, but everywhere in the world.

Comments (2)

[…] channel across the African continent. Running through the pictures, historian Mohamed Gamal-Eldin discovered, was a striking pattern. For the technological sublime to work its wonder on the awed spectator, […]

[…] : Egyptian Streets, 14 septembre […]