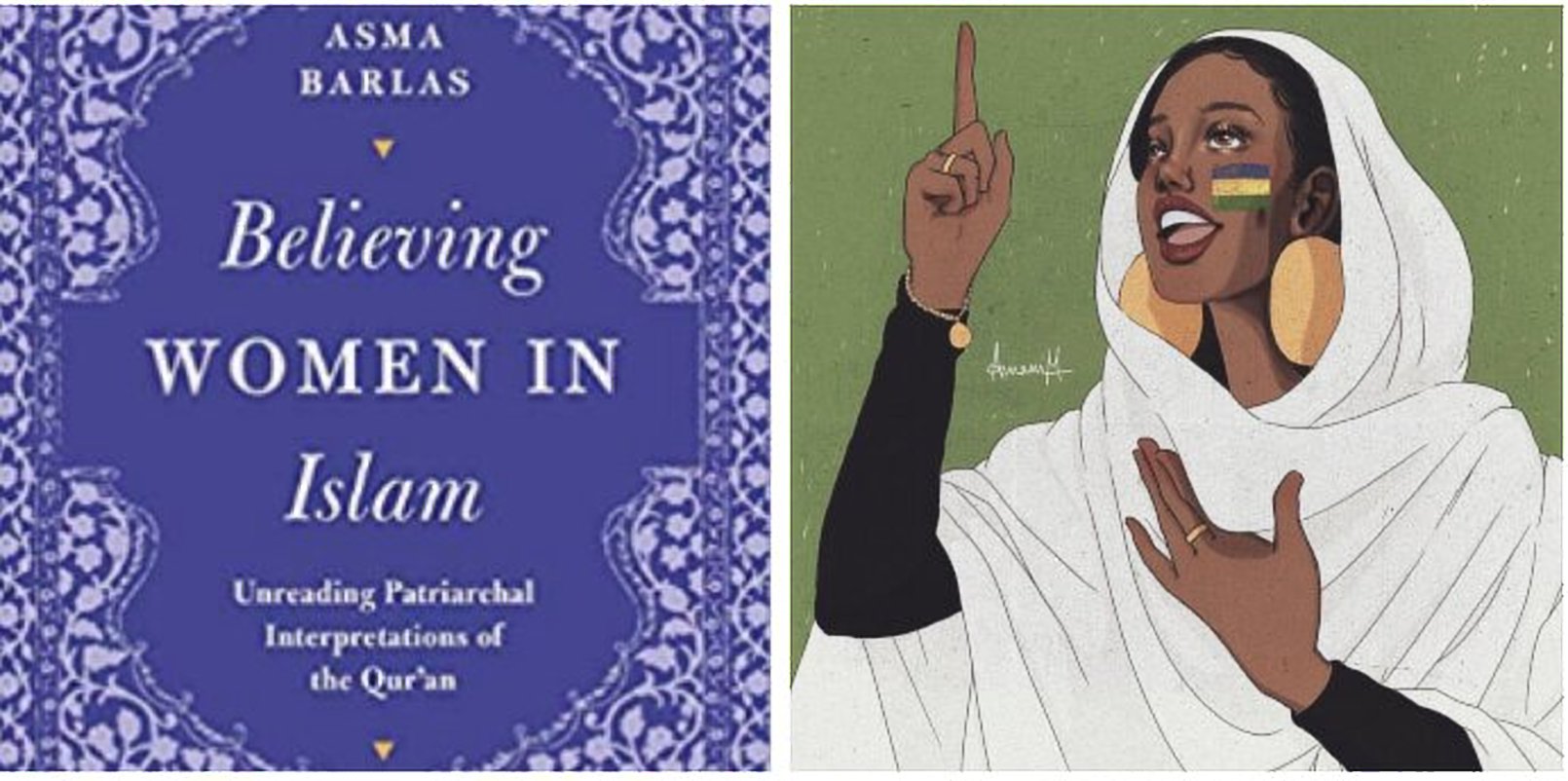

Muslim feminists have two tedious battles to fight: one against those who hold on to patriarchal notions within their own community, and the other against feminists who refuse any reconciliation between feminism and any ‘Abrahamic’ religion, including Islam. From both sides, they are belittled, misjudged and dismissed. In ‘Believing Women in Islam’ by Saqi Books, Asma Barlas takes on these two battles with precision, clarity and a clear purpose: first, to ask whether Islam’s scripture condones sexual inequality and oppression, and second, whether Islam permits or encourages liberation for women.

Barlas begins tackling the former by critiquing patriarchal interpretations of the Quran. First, she starts by clearly defining ‘patriarchy’, and what it means for scripture to be patriarchal. Narrowly defined, patriarchy is a ‘mode of rule by fathers’, that is, it assumes a real relationship between the ‘father’ as a male figure and God, and extends this to the husband’s claim to rule over his wife and children. Barlas also adds on to this definition by including the politics of sexual differentiation that privileges males and transforms biological sex into a politicized gender, and thus, it is an ideology that produces social and sexual inequalities by ascribing it to biology.

With this understanding of patriarchy, the mission is now set clear – to explore whether the Quran is a patriarchal text. This approach is quite significant as it clearly sets the boundaries on how Barlas will examine the Quran, rather than approaching it with a very general and hazy understanding of patriarchy. With this approach, Barlas moves down a ladder in her book by examining each aspect of the Quran.

To start with, the idea of viewing God as a male figure is critiqued. Barlas highlights that there is a contradiction between the theories that assert male authority over wife and children and that men are intermediaries between God and women and the principle of God’s unity (Tawhid). The idea of Tawhid implies indivisibility and indivisibility of God’s sovereignty, and hence, the theory of male sovereignty partaking in God’s rule is in fact incompatible with the doctrine itself.

Second, another principle of God’s self-disclosure in Islam is that though “severe, strict and unrelenting in justice,” God never does zulm or injustice to anybody. If God means justice, then ultimately, any reading of the Quran that justifies injustice against another human and attributes it to God contradicts that principle. The third principle is that of incomparability, as the Quran rejects God’s sexualization/engenderment as Father or male, and thereby, there should be no reason to hold any connection between God and males.

Before diving into the Quran’s teachings, Barlas starts by taking the Quran as a whole and looks at the bigger picture. She mentions that the Quran provides a specific methodological criteria for reading it, which includes searching for the best meanings and using analytical reasoning, as well as the importance of textual unity.

“Those who break the Qur’ān into parts. Them, by thy Lord, We shall question, every one, Of what they used to do” (15:91–93).”

The Quran also warns against reading it in a decontextualized manner, as it refers to the Israelites who broke their covenant with God and used the scripture for wrong reasons and objectives.

“They change the words From their (right) places And forget a good part Of the Message that was Sent them” (5:14).”

And “they change the words From their (right) times And places” (5:44).”

It is also important to note that Barlas uses four translations of the Qur’an for analysis and interpretation in her book: Abdullah Yusuf Ali’s translation, Muhammad Asad, A. J. Arberry, and M. M. Pickthall. This reflects her aim in addressing both Arab and non-Arab/non-Muslim audiences, and throughout her analysis, she clearly shows how certain translations of one word can change the entire meaning of a text, proving her point that cultures and customs play a role in interpreting the Quran’s message.

In the first part of the book, Barlas analyzes all of the texts in Islam, from the primary texts (Qur’an, Tafsir, Ahadith) to the secondary sources (the Sunnah, Shari’ah, and the state). She delves into the historical contexts of these sources and then analyzes how certain methodologies developed over time, such as the growing interest in rhetoric over rationalism, and how in certain schools, there was an attempt by the ulema or scholars to define a religious canon and institute their own interpretive authority. The conservative nature of Muslim methodology also resulted from the alliance between political and sexual power, as during certain periods of time, the state was privileged over civil society, and men over women, and any dissenting voices within Islam were suppressed and flogged for “political dissent”.

However, Barlas does not just focus on the crisis of reading the Quran in the past, but also in the present, as she points to ongoing attempts by the United States to “reform and reshape Islam” in the aftermath of 9/11 and global terrorism. What this leads to is the “hollowing out Islam from the inside”, which she argues as destructive as it puts Muslims in a position to choose between binaries of Islam and democracy or Islam and women’s rights, in the hope that Muslims will eventually opt for secularism even if it means completely neglecting Islam.

Instead, Barlas chooses to examine the Qur’ānic narratives of the prophets Abraham and Muhammad and looks at Islam’s relationship with feminism from within. To emphasize her point that God did not allow fathers/males rule, Barlas presents the story of Abraham and the sacrifice of his son, rejecting the interpretations that argue that it proves one must abide by the rules of a father figure, putting faith over ethics.

Instead, Barlas looks at other interpretations that include a comprehensive view of Quran’s teachings, which rejects blind obedience to parents if they “strive To make thee join In worship with Me Things of which thou hast No knowledge (3:14–15)”, as well as that each soul is answerable only for “herself” and no one can “Bear another’s burden . . . [e]ven though he be nearly Related” (35:18).

Barlas points that in the story mentioned in the Quran, Abraham does not ask for his son’s obedience, but asks him for what he makes of his dream. What we see is not a test of Abraham’s faith, but instead, of his knowledge, as the question was now whether to interpret the dream or act on it literally.

From this story, Barlas extracts an important piece of wisdom, as when Abraham finds out that he was not ordered to sacrifice his son by God, it signifies that literalism is not the essence of faith, and that God’s will is not transparent but must be interpreted.

“These are particularly compelling reminders at a time when so many Muslims are bound to textual literalism, when they see reason as an obstacle to faith, and when male hubris has reached such heights that a handful of (mostly Arab) men can claim to know the truth as it resides with God,” she states.

In the next chapters, Barlas then focuses on specific scripture that address veiling, divorce, and the rights of fathers and mothers to illustrate her position of female equality/liberation. In regards to the issue of veiling, she distinguishes between two different notions of the veil mentioned in the Quran – one specific and the other general – as the purposes of veiling in the verses differ.

“In the first set, the jilbāb is meant not to hide free Muslim women from Muslim men but to render them visible, hence recognizable, by Jāhilī men as a way to protect the women. This form of “recognition/protection” took its meaning from the social structure of a slave-owning society in which sexual abuse, especially of slaves, was rampant,” Barlas argues.

Barlas’ acknowledges the struggle of changing the reality and life of Muslim women today through her work, yet she hopes that the intention to strive for justice and knowledge and reread the Quran will encourage further work and action.

Today, we already see Muslim women striving to change their societies by their own will, such as Alaa Salah, who became an ‘icon’ of the revolution and broke the internet with a photo of her atop a car roof addressing thousands of Sudanese protesters during the uprisings.

In a tweet, managers of her account state “They burned us in the name of religion, Thawra (revolution), They killed us in the name of religion, Thawra, They jailed us in the name of religion, Thawra, But religion is not to be blamed, Thawra.”

https://twitter.com/iAlaaSalah/status/1116645732839231488

Both Barlas and Salah are symbols of a revolution that is yet growing. As Salah protests with her voice for equality, Salah protests with her scholarship, and as such, we see civil society rise over the state, and dissenting voices over authoritative voices.

Comments (0)