In light of the recent backlash Egyptian actress and comedian Shaimaa Seif faced after appearing in an episode of the Ramadan prank program ‘Shaklabaz’ wearing blackface to portray Sudanese women, Egyptian actor Maged El-Masry spat racist remarks towards African women when he appeared on the show ‘Sheikh El-Hara’ hosted by Basma Wahba resulting in the show getting suspended by Egypt’s Media Syndicate.

In an on-air interview, El-Masry recounted with the host a what he considered a “funny” story of a “prank” his friend played on him. El-Masry said that his friend told him that three female fans really wanted to meet him and decided to meet at Roxy Square. When he arrived to Roxy Square that night, three women wearing veils covering their faces hopped into his car.

The moment they exposed their faces he was horrified at the sight of their dark skin complexion revealing that they are ‘African’. Wahba was very amused by his reaction and continued to laugh while he revealed that he literally kicked them out of his car. In case him saying it was not vile enough, El-Masry gestured how he kicked them out of the car, by literally kicking his foot in the air, as Wahba’s laughter grew louder.

Since the episode aired on May 19, a massive wave of backlash hit social media criticizing both El-Masry for his racism comments and Wahba for her reaction, an ample amount of people filed complaints to the extend that the Media Syndicate banned the show from being aired effective immediately for breaching ‘professional and ethical standards’.

“The episode also violated the law of the Media Syndicate No. 93 of 2016, which prohibited the practice of media activity without registration in the syndicate’s schedules or obtaining a permit to practice a profession, as she (Basma) did not formalize her activities with the syndicate and is not bound by any registration schedules. She did not obtain a permit to practice the profession in accordance with articles 2-19 of the syndicate’s law,” Head of Media Syndicate Tarek Saada’s official statement read.

Following the backlash, El-Masry told Youm 7 news website that he was just “joking” and did not mean to offend anyone, because “I am African too.”

“I misspoke. I apologize to anyone who was offended,” the actor said.

Wahba, meanwhile, announced that she is resigning form the show in protest to stop Al-Kahera Wel Nas, the channel that airs the show, from airing reruns of another controversial episode.

In the time I am writing this article, the video of the episode has been removed from YouTube as well.

Like I mentioned earlier, this is not the first incident that takes place this month, and certainly not the first racist debut in Egyptian television and media for the portrayal of Sudanese and other African cultures during the month of Ramadan under the cloak of “comedy”.

I say “Sudanese” because in my experience, Egyptians categorize any person who is “dark-skinned” as Sudanese regardless of their true nationality.

With that being said, some depictions have been intended to in fact depict Sudanese people such as Seif’s character in ‘Shaklabaz’. And while Seif was wearing blackface in multiple episodes on the show, which was airing in MBC Masr, this particular episode drew so much controversy and angered so many Sudanese people calling to boycott the network to the extent that MBC had to issue a statement saying they had nothing to do with the production of the show.

In the episode, Seif attempts to speak in a Sudanese Arabic while trying to translate what seems as gibberish form of Sudanese “language”. Both characters where represented as “loud” and “uncivilized”, a common stereotype Arabs and Westerners associate with Africans.

Meanwhile, Seif said “I am a comedian doing comedy. I wished that you would view the matter in the comedic context that was intended. Of course I did not mean to upset you,” before suspending her social media accounts because she was receiving hate from both the Sudanese and Egyptian audience. The promo of the episode has since been removed from Twitter and Facebook.

In recent years, this seems to be a common theme in Ramadan.

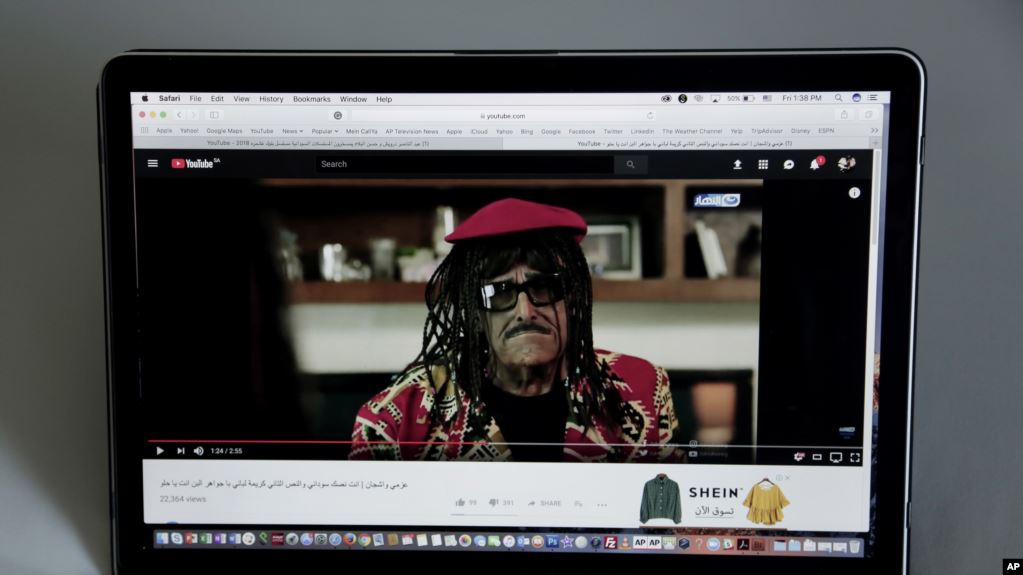

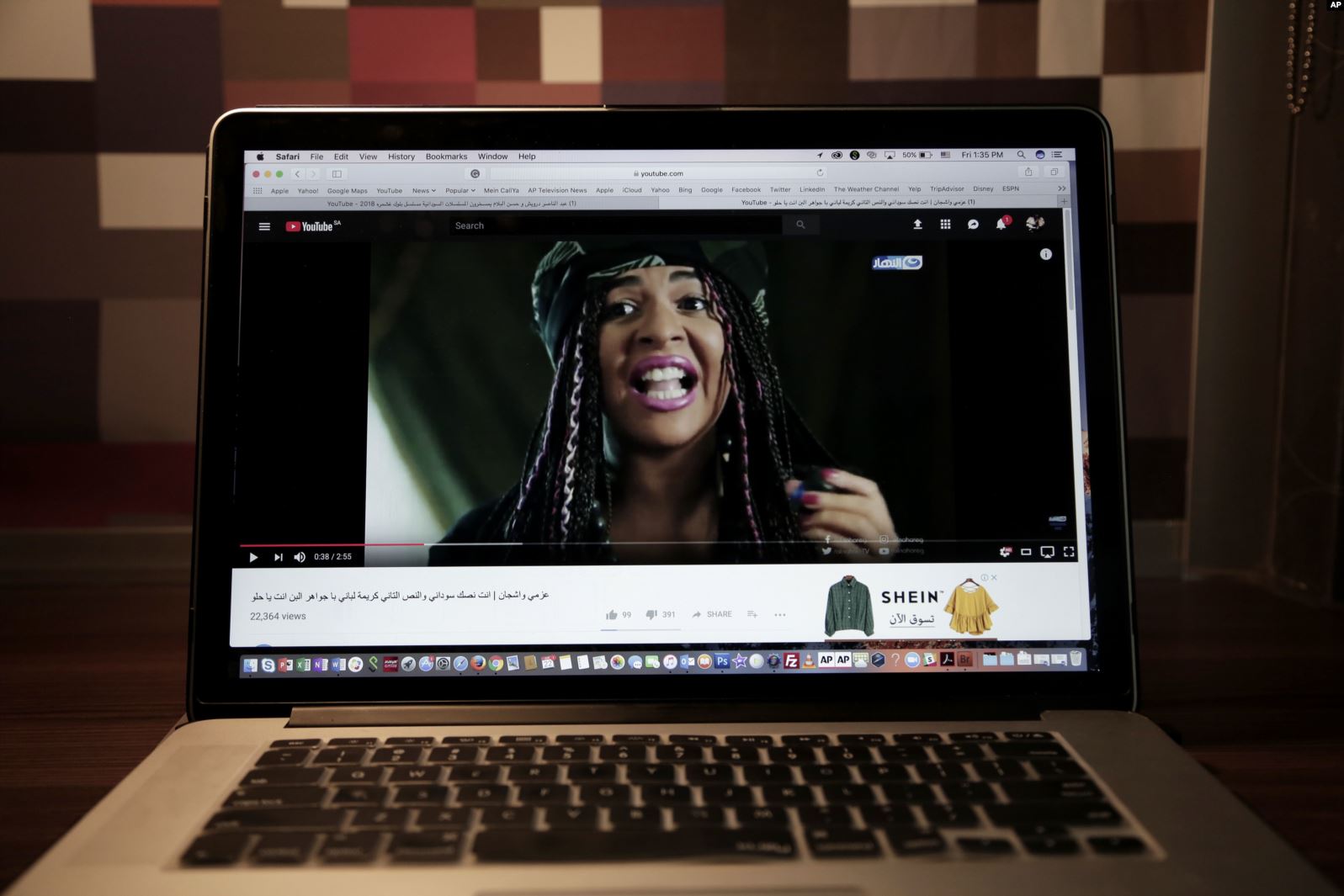

Last year, a show starring Egyptian comedian Samir Ghanem and his daughter Emy Samir Ghanem called ‘Azmi We Ashgan’ aired in Al-Nahar TV channel. Both Ghanems wore blackface and dreadlocks to mimic African culture. ‘Ashgan’ , played by Emy, was Sudanese Malawian housemaid working for an older Egyptian man.

The man attempted to make sexual advances towards her prior to her father’s arrival. Her father then asks the man if he can live with them in his house to which the man responded saying “Did I get this house for fun or did I buy it to set free some slaves?”

What is different this year is that the media channels received criticism from a Sudanese and an Egyptian audience, when usually it was only Sudanese people who would voice their disappointment. However, Egyptians started opening their eyes to discrimination.

For the first time, the Media Syndicate took a stance against discrimination based on race by banning a show for racist comments. Although, I am not sure why this particular incident was triggered a reaction for the Media Syndicate, this is an astounding step, because blackface and racist slurs in Egyptian media are nothing new.

In fact, I am almost certain that anyone who watched or was a fan of old Egyptian cinema, is familiar with the character “Osman” who is often a dark-skinned man working as a servant for a “beh”, a “basha” or an “afandy”, all of which are titles of pride.

In other occasions the “Osman” character would be the laughing stock of the scene for the sake of “comedy”. Sometimes, he is not played by a dark-skinned character and instead the actor has to paint his face literally black and speak in an exaggerated perception of a “Sudanese” accent, an Arabic version of blackface, which is considered racist. In other occasions, “Osman” is a Nubian actor who takes the role of a house guard, servant or cook, a depiction many Nubians consider “a black spot in Egyptian cinema.”

All of these derisive portrayals in the media over decades have normalized racism in the country specifically against dark-skinned people even if they are Egyptian such as the case with Nubians residing in Upper Egypt. And these comments have smeared on to the day-to-day life of a dark-skinned person in Egypt.

Racism can no longer hide behind the facade of “comedy,” because mocking and shaming someone for their skin color, features and accent is obnoxious and now, at the very least, is less acceptable than it used to be with potential repercussions.

In an interview with Al-Jazeera new channel, Middle-East History professor at University of Pennsylvania, Eve Troutt-Powell said that blackface has “been a trope in Egyptian entertainment for over a century”.

“There is a larger history at play behind the racist caricatures of black people in Egypt and other parts of the Middle East as well, and that is the history of slavery,” the professor said.

A part of Arab history that is often concealed is the Arab Islamic slave trade that lasted for over a thousand years and continues to create tension between the racial dynamics in the region to this day. Surprisingly, Arabs have a much longer history with slavery than Westerns do.

While discussing the subject of his book Islam’s Black Slaves: The Other Black Diaspora, South African writer and activist Ronald Segal explains “Arab or Islamic slave trade began in the middle of the seventh century and survives today in Mauritania… With the Islamic slave trade, we’re talking of 14 centuries,” as opposed to the duration of the European or Atlantic slave trade which lasted four centuries. “The gender ratio of slaves in the Atlantic trade was two males to every female, in the Islamic trade, it was two females to every male.”

And although there is no racial or ethnic signifier to slavery in the context of Islam, most Arabs imported slaves from Africa and South Asia most of which were non-Muslims.

However, the Arabic word for slave, abed, is now used as a racial sobriquet for people with dark complexion to this day. According to Mona Kareem, a research fellow at the Forum Transregionale Studien in Berlin, the slur indicates that “blackness as something to fear or ridicule”.

“A fixation on skin tone is only an expression of … racial bias, and does not capture the complexity of the racial experiences that blacks have had in the Arab world,” Kareem elaborated in an interview with AFP news agency. “Many of these representations (on television) give voice to already-existent racial images and myths.”

Blackface has been deemed as a racist act in the Western World where, if practiced, results in an extreme form of outrage. However, this same energy is not carried out throughout the Middle East, as people are still questioning whether or not it is really racist. Some people’s justifications for blackface in the Egypt and the Middle East has been: we are trying to connect to your culture, we are all Muslims, we are Africans too, we too are a minority who are subjected to racism by the West, therefore it is almost impossible to be racist and so on and so forth.

On the other hand, these perpetuating images make it difficult for black people living in the Middle East to integrate within the society, because they continue to be marginalized for their skin color.

“It seems, particularly in comedy, that a clear-eyed and heartfelt discussion of political and racial history still needs to take place in Egyptian society,” said Troutt-Powell. “And it must also continue in other societies.”

Any opinions or thoughts expressed in this article do not reflect the views of Egyptian Streets’ editorial team. To submit an opinion piece, please email [email protected]

Comments (3)

[…] actor Maged El-Masry also spat racist remarks towards African women when he appeared on the show ‘Sheikh El-Hara’ hosted by Basma Wahba, […]

[…] Read more at Egyptian Streets. […]