Today, cheap and reliable fossil fuel defines the way we live and our energy consumption—from transportation to entertainment and even our food supply chains. It seems nearly impossible that this can change overnight, but the reality is that we must prepare to change the way we have operated for centuries.

The topics of going green and energy transition have been gaining momentum in the last couple of years, but even more critically important than exploring these subjects is to ensure that these conversations remain grounded in reality.

While the Middle East and Africa region relies mostly on traditional energy sources, there have been a number of projects and initiatives aimed at diversifying energy sources, which revolutionize how we live in the future. One of the most notable examples is the development of a hydrogen economy in the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

In February 2019, the Dubai Electricity and Water Authority launched the first solar-driven hydrogen electrolysis facility, the Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Solar Park, in the region in Dubai. Two years prior, in 2017, Al Futtaim Motors, in partnership with Air Liquide, also opened the first hydrogen station in the Middle East at Al Badia,

Dubai Festival City. Similarly, the Emirates National Oil Company (ENOC) is planning to unveil a ‘Service Station of the Future’ for the Expo, the world’s greatest event celebrating innovation, which will use multiple sources of energy, including solar and hydrogen fuel.

In Saudi Arabia, the kingdom is building a green hydrogen plant in its future smart city, a project described by the government as a ‘new vision of the future’. The plant will be powered by 4 GW of wind and solar power and will produce 650 tons of green hydrogen daily, enough to run approximately 20,000 hydrogen-fueled buses.

Egypt isn’t far behind. Earlier this year, President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi expressed his keenness to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) in new and renewable energy sector during a meeting with representatives from Belgian companies looking to invest in the production of green hydrogen. In addition to boosting local industry, investment in the production of green hydrogen is also expected to enhance port movement and ensure strategic access to the European energy market.

But what is a hydrogen economy? In short, it is one that replaces gasoline as a transport fuel or natural gas as a heating fuel, with water as its only byproduct. It has the potential to fuel cars, buses, airplanes, as well as heat buildings, and can also be liquefied, stored, and transported through pipelines.

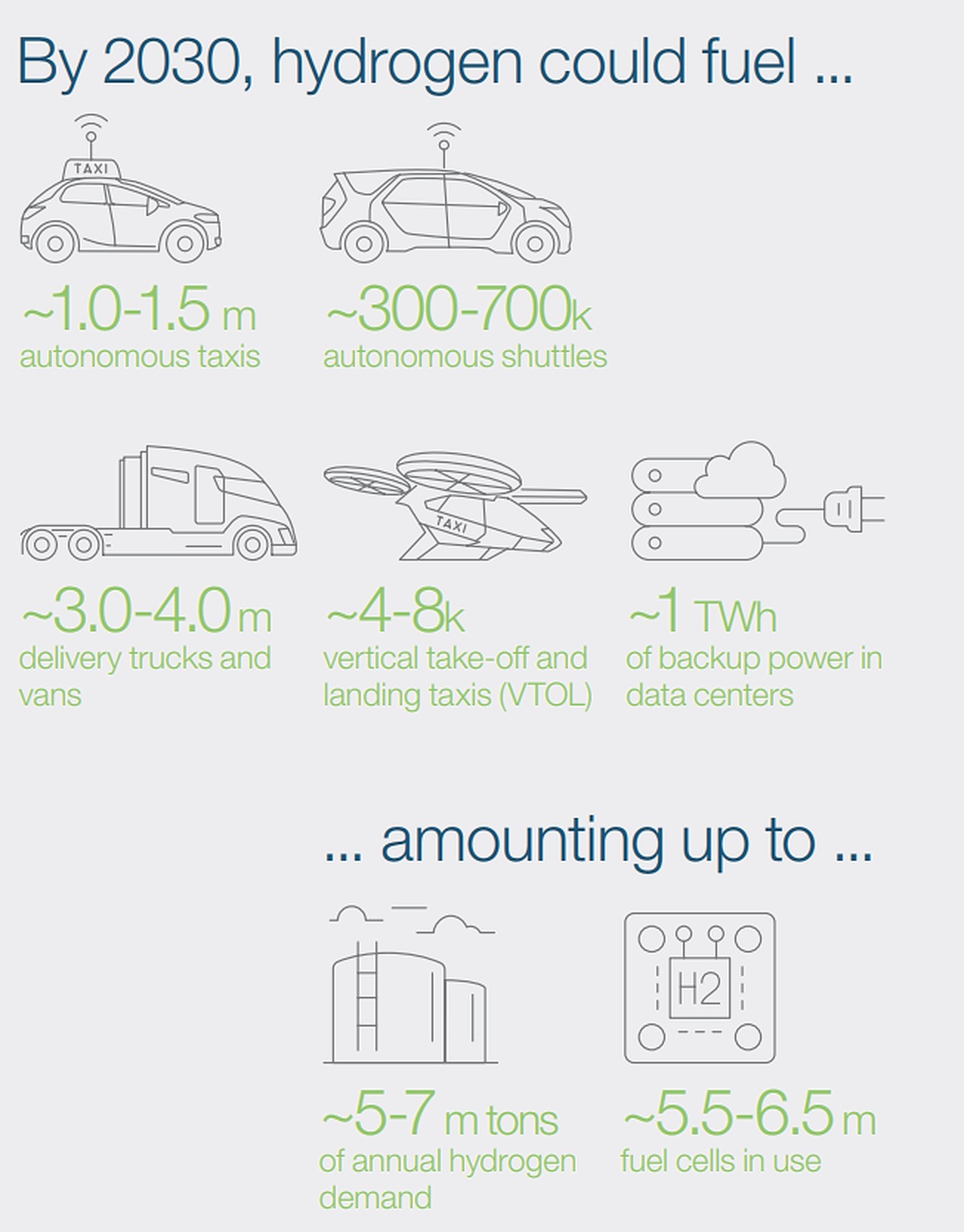

The Hydrogen Council, a global initiative of 92 leading energy companies dedicated to developing the hydrogen economy, estimates that by 2050 hydrogen may power more than 400 million passenger cars worldwide and up to 20 million trucks and 5 million buses.

A new report by entitled Path to Hydrogen Competitiveness: A Cost Perspective also shows that by increasing hydrogen production and distribution, the cost of hydrogen solutions can decrease by up to 50 percent by 2030, which can become a viable alternative compared to other options.

However, despite evidence there’s a future in hydrogen power, it is still not widely used as a clean-energy solution due to the lack of clear policies, investment, and international cooperation. Policymakers, researchers, industry leaders and other stakeholders in society must work together to design rules and the right policy environment for the harmonizations of regulations and for energy markets to coincide.

Heinz J. Sturm, founder of the Bonn Climate Project, which is implemented by the Germany-based International Clean Energy Partnership (ICEPS) and Climate Technology Center (CTC), is an advisor for governments and organizations on hydrogen economy and a main advocate for the energy transition. The Bonn Climate Project currently offers joint research with governments and environmental organizations, as well as on-ground concepts and solutions that were implemented in the German city of Bonn, such as fuel cell boats.

Sturm’s interest in developing clean energy sources piqued when he traveled to other countries and recognized the essential value of energy supply. “I recognized the connection between poverty, simple farming and livestock breeding, energy shortages and lack of infrastructure. It struck me that lack of energy supply is the main cause of poverty and that without energy, no infrastructure development can take place and people will remain poor,” he says.

Sturm also realized very early on the importance of understanding the threats of climate change and clean energy resources, which he acknowledges are not easily available to people in other parts of the world. “In 1997, for example, the UN Climate Secretariat was opened in Bonn in Germany, which is only a few kilometres away from my home. I was always informed through the press about climate protection, climate change and the problems of many countries that suffer from climate change,” he notes.

In 1999, based on his technical training and work in the field of clean energy, the importance of hydrogen in climate protection was embedded in his vision for the future of energy projects in rural areas. “I realized back in 2000 that steam reforming of biomass and waste-derived products provide an opportunity for producing hydrogen from renewable and sustainable sources and would solve the energy problems of many developing countries,” Sturm explains.

Egypt produces around 50k-60k tonnes of solid waste per day, totaling 22 million tonnes annually, according to the Waste Management Regulatory Authority (WMRA). Addressing this waste management problem can result in turning environmental hazards into clean and renewable power instead, which includes generating hydrogen through a biomass gasification process involving heat, steam, and oxygen.

“Ultimately, steam reforming and thus the decentralized production of cheap hydrogen gas from biomass waste is the only affordable and sustainable [and technically feasible] solution for producing energy in remote areas. In this respect, it will also prevail and become more and more popular, because people do not have the money for expensive high technologies,” he adds.

Many African nations remain dependent on exporting fossil fuel and consider it as a main economic strategy. NJ Ayuk, chairman of the African Energy Chamber, notes that “natural gas is by far the most economically sustainable way of producing power in enough quantities to fuel economic development,” and that demonizing energy companies undermines African countries’ best opportunities for economic development.

As such, the debate on how we can move forward and set a global climate policy through international cooperation becomes extremely critical. And while there is extensive research on emerging technologies that can be used as alternatives for pollution, ensuring that all countries have equal access to knowledge and application is also vital.

In cooperation with the German government, Sturm’s strategy to promote a hydrogen economy for Arab as well as African countries in the region is currently being used and researched by the UN Climate Secretariat to be widely applied and popularized. “As a participant in the UN climate conferences, I have known for many years that German technologies are not accepted abroad. In addition, their technology is still geared towards electric renewable power, which makes the introduction of new technologies in most countries of the world more difficult, more expensive and thus practically unfeasible,” he says.

However, Sturm highlights that the production of “green hydrogen exclusively via electrolysis” and “cheap electrolysis plants” will be available in the market by 2040, which can only lead to a further delay in climate action. A more realistic alternative is to shift from an electricity-led energy transition to a gas-fueled model. This is because gas, as an energy source, can best be produced cheaply and affordably through the thermochemical gasification of biomass (waste), which also includes organic waste of all kinds, including household waste.

The next decade will be caught between opposing scenarios; from surviving to thriving, scarcity to abundance, recession to growth. Yet for international climate protection to succeed, however, international cooperation must take a holistic view of politics, climate policy, geopolitics, development policy, and social policy. It is also essential to realize that it is not just about meeting climate targets policies, laws or reducing emissions, but also about putting people, and particularly marginalized areas, first.

Comment (1)

[…] Source link […]