Egypt is no stranger to unrest – rather, it seems to embrace the instability with enough grace to remain standing after upwards of three revolutions in the past half-century alone. Those at the forefront of these movements, however, are not always loved; from death threats to feminism, from socialist agendas to anarchy, Egyptian revolutionaries have always pushed the envelope.

Some would argue a little too far.

That does not stand in the way of their legacy as game-changers and status-quo shakers. Here are some of Egypt’s most infamous, most love-hated, and most daring controversial figures.

Akhenaten | r. 1353 – 1336 BCE

Father of Egyptian revolutionaries was, to no one’s surprise, a Pharaoh: a king who seemingly had it all if only to gamble it on a fit of manic, religious freedom. Born circa 1353 BCE, Akhenaten was pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt’s New Kingdom. Initially named Amenhotep IV, Akhenaten changed his name after only five years of sovereignty.

Many mistakenly believe that Akhenaten disregarded the entirety of the Egyptian religious pantheon for the emergence of a new deity, the Aten; in reality, the cult of the solar-deity has been around but fully came into focus and worship with Akhenaten’s decision.

Though names are hardly what earn him his notoriety; in a world of avid paganism and love for a pantheon of gods, Akhenaten compressed Egyptian belief systems into a single, alleged ‘monotheistic’ religion – the first of its kind in the world. For his disregard of the long-established priesthood systems in the country, as well as Egypt’s deeply rooted cult centers for its multitude of deities, he was dubbed as a Heretic King who dislodged the gods and changed the capital from Thebes to Amarna- the city he founded.

His era, the Amarna Period, is considered the “the most controversial era in Egyptian history and has been studied, debated, and written about more than any other.” This was not solely due to the religious shift, but the accompanying diverging style that resulted as well, breaking the tradition of established aesthetic and artistic conventions.

Gamal Abdel Nasser | r. 1918 – 1970 CE

His is a name every Egyptian knows – but how it’s spoken and in what context tends to depend on the individual. Gamal Abdel Nasser is a divisive figure, and by far Egypt’s most well-known revolutionary. As a military leader, he staged the coup d’etat of 1952 to overthrow the corrupt Wafd Party, effectively ending British colonialism in Egypt.

He became the second-ever President of Egypt following Mohamed Naguib, and proceeded to enlarge the bureaucratization of the state; unfortunately, this came with military mindsets which worked for the “empowerment of state security forces to limit speech, assembly, and other constitutional rights granted to Egyptians.”

Despite this, he was much-loved during the era of blind pan-Arabism in the mid-20th century. After shattered optimism during the Six Day War of 1967, Abdel Nasser’s judgement was brought into question. From proceeding economic deterioration and mis-applied socialism, to the exodus of Jewish-Egyptian populations and the displacement of Upper Egypt’s Nubian populace.

Moreover, many still harbor ill-feelings towards the charismatic figures for the sudden destitution families, and companies found themselves in: overnight, houses were confiscated and businesses snatched.

On the other hand, it was Nasser’s ambitious project to ensure that education and healthcare would be available for all that revolutionized and democratized opportunities for Egypt’s population.

It seems that, for Gamal Abdel Nasser, some ends justified their means.

Naguib Mahfouz | r. 1911 – 2006 CE

Novelist, Nobel Prize laureate, and lover of literary faux-pas: Naguib Mahfouz is a force to be reckoned with. Growing up in Cairo’s al-Jamaliya district, he attended Cairo University for a degree in Philosophy. Soon after, he would move on to write some of Egypt’s most important, albeit notorious, masterworks – some of which have earned him esteem and hatred among the locals.

Mahfouz offered cynical views on contemporary Egypt, colonialism, and the unseated monarchy. He earned the Nobel Prize for Literature for his Cairo trilogy: a deeply-critical, openly tragic set of novels delineating patriarchal hypocrisy, violent politics, and the dovetailing of love, religion, and social taboo.

His most controversial piece, however, comes in the form of Awlad Haretna, or rather Children of the Alley (1996). After personifying elements of Islam, including God and prophets, the book was banned in Egypt for having based characters off of key figures and spiritual elements.

Islamic militants have, on countless occasions, called for his death and in 1994, Mahfouz was stabbed in the neck. Regardless of these attempts on his life, he would go on to become one of Egypt’s most notable, esteemed figures in literature.

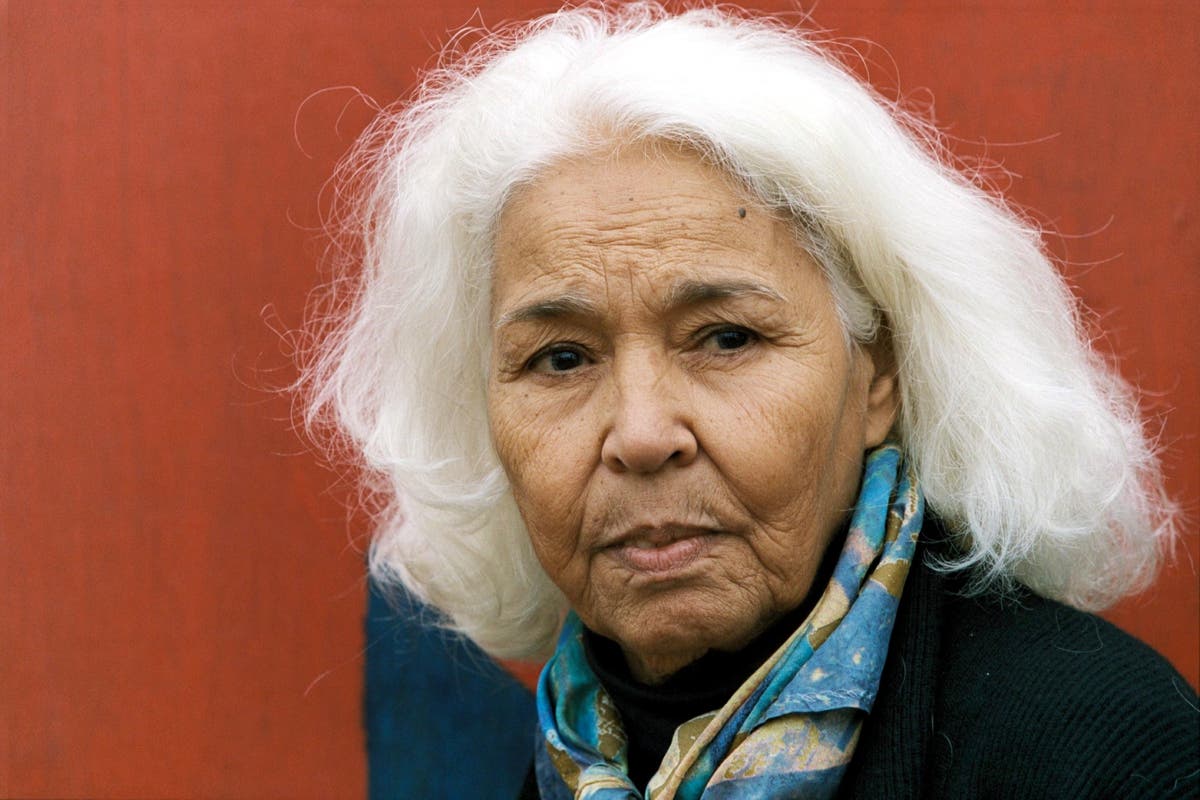

Nawal el-Saadawi | r. 1931 – 2021 CE

There are few feminist Egyptians today that have not heard the name of Nawal el-Saadawi. Not only has she defined the modern feminist movement locally, but has garnered international attention for her work. Born in 1931 in Cairo, el-Saadawi was a writer, activist, and physician that sat at the forefront of Egyptian activism for decades.

Over the years, much like Mahfouz, she has had death threats made on her life following her writings and lectures on discrimination against women. Her demand for equal rights stemmed from her personal history and experience as a doctor treating women in rural Egypt. She is cited as claiming her medical education was “invaluable” and a major influence in her life.

El-Saadawi was forced into exile in the early 1990s, after her name featured on an Islamic fundamentalist hit list. She remained at Duke in the United States until her death in 2021.

Alaa al-Aswany | r. 1957 – Present

The only one listed who remains active today, and remains widely infamous, is Alaa al-Aswany: an outspoken, vocal critic of military rule, with special attention to the autocratic, late president Hosni Mubarak. Born to Abbas al-Aswany, a lawyer credited with the revival of maqamah (anecdotes written in rhymed prose), he developed a love for both law and literature.

As an avid supporter of the Egyptian uprising of 2011 and founder of the Egyptian movement i, al-Aswany wrote several books on the matter, including On the State of Egypt (2011) and The Republic of False Truths (2018) – the latter of which was banned in Egypt for its continual and candid critique of state institutions.

In March of 2019, his column in Deutsche Welle was the source of a lawsuit; it criticized President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi and the questionable role of Egyptian armed forces in civilian government. Today, he resides in Brooklyn, New York within the United States after being banned from appearing on television, holding his literary salons, writing his weekly column in the Egyptian newspaper al-Masry al-Youm or publishing more books.

Comments (4)

[…] of the controversial. Over his nearly 50 published novels, Naguib Mahfouz has earned himself a ferocious set of adversaries. Touching on the taboo and the unsavory in his Cairo Trilogy, while dabbling with personifications […]

[…] ثوار مصر المثيرون للجدل […]