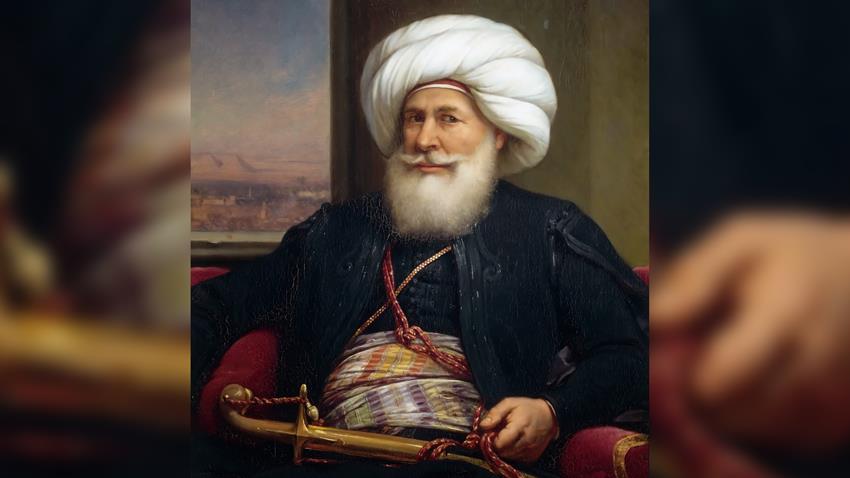

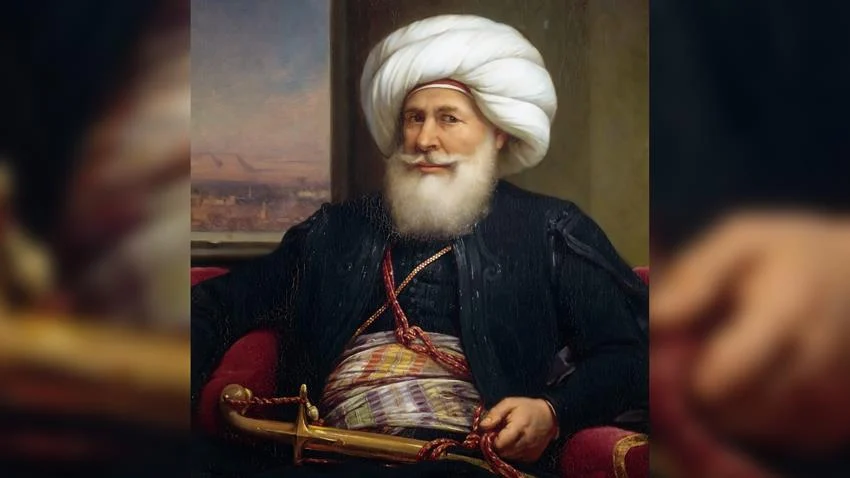

The engineer of Egyptian modernity was not Egyptian – he was Ottoman. Muhammed Ali is a prolific name, one potent in political and scholarly circles. Some would argue for good reason: here was a man who attempted ripping Egypt from the fabric of an oppressive Ottoman Empire in a move for the throne. Muhammed Ali was not only the father of Egyptian modernity, but became a central artery of its history to this day.

He granted the state its first illusion of autonomy after several millennia, and strove to redevelop Egypt through newfound, localized modernity. From a dilapidated intellectualism and rampant poverty, the Ottoman and Mamluk reigns had done little but ensure stagnation; the mission at hand was labor intensive, but through exhaustive – arguably absolutist – means, Muhammed Ali brought Egypt to the forefront of the 19th century and “put an end to Egypt’s traditional society.”

Birth of A Viceroy

Not much is known about Muhammed Ali’s youth, and it is this elusive, obscure youth that has helped his history interweave well with Egyptian idolization. What is certain, however, is that Muhammed Ali was born in Kavala, Macedonia to a Muslim Ottoman father in 1769. Some sources argue that he might have possessed Albanian roots, although there is little supporting evidence to say so with any degree of certainty.

His father, Ibrahim Agha, was the chief commander of a minute military force maintained by the governor of Kavala. The governor is credited with Muhammed Ali’s upbringing despite passing shortly after Ali’s boyhood. In honor of his placement in the family, and perhaps his father’s service, Ali was wed into the governor’s family at the age of 18 and involved himself in commercial endeavors – largely that of the blossoming tobacco network that’d seen a peak during the era.

While his interest in the commercial would later resurface, it initially took a backseat to his ambitious political inclinations. In 1801, Ali arrived in Egypt as the commanding officer for a “300-man Albanian regiment sent by the Ottoman government.” It was a candid attempt to oust the French from the region, and with deft political savvy, tactical smarts, and British aid, Ali earned himself the title of wali – the Ottoman Sultan’s viceroy in Egypt – shortly after his successful coup in 1805.

“Nowhere in the Ottoman Empire was there greater opportunity for a total restructuring of society than in Egypt,” and Muhammed Ali had found himself at the forefront of a virgin opportunity. The French’s short stay in Egypt had confused its natural, traditional facilities and altered its economic structure; rather than returning Egypt to what was essentially glorified farmland, Muhammed Ali embraced the French initiative and eradicated what remained of Egypt’s traditionalism.

Viciously, he massacred the Mamluks, the former oligarchy, “expropriated the old landholding classes, turned the religious class into pensioners of the government, restricted the activities of the native merchant and artisan groups, neutralized the Bedouins, and crushed all movements of rebellion among the peasants.”

Muhammed Ali had left Egypt vulnerable to his vision.

By 1808, after crushing local revolt and repelling both British and Ottoman intervention, Ali seized power over all of Egypt. Thus, dreams of removing Ottoman rule entirely had begun to take shape in his mind.

A Man of Native Intelligence and Reform

Muhammed Ali’s agenda was sweeping and advantageous; reforms were dealt to every pillar of society. In order to both fortify commercial revenue and strengthen his own position as Egypt’s independent sovereign, he devoted resources to scientific and intellectual missions, and established a well-rounded and fully-equipped agricultural sector. He is credited with enhancing Egyptian cotton exportation and refining processing and manufacturing industries as a whole.

This saw the establishment of an independent divan for Egyptian trade. Not only did this mark the first local trade council in centuries, but gave Egyptians an upper hand in the negotiation of import and export goods.

Ali’s efforts were not, however, all commercial; a large subset of his agenda served Egypt’s military needs and its healthcare sectors. Under his diktat, the first military school was established in Aswan and the first Egyptian military school was, subsequently, established in Paris.

After witnessing first hand the delict facilities, Ali “established the health council, schools of medicine and pharmacy, school of obstetrics and nursing and Qasr Al-Ainy School of Medicine. He also started to apply compulsory vaccination.”

Still, it is worth noting that excessive taxation is credited as stunting many of Ali’s endeavors, alongside military conscription of the peasantry, and his monopolization of trade. It was becoming increasingly clear that what may have started off as a pseudo-philanthropic attempt at bettering Egypt was devolving into a “massive plantation [site] for [Ali’s] own benefit.”

Fractured Ideation

The notion of stealing Egypt away from the Ottoman Empire became a possessing vision of Ali’s: he wanted to break the hold the Turks had on Egypt, in a vicious leap for the throne. Although he won several wars in his quest for expansion and independence, Muhammed Ali’s dreams of regional domination were cut prematurely short by European intervention in the region. It is this very intervention, primarily freeing Syria from Egyptian rule, which ended Ali’s hopes for “greater independence from the Ottoman Empire.”

It was not all for naught, however; by 1841, Muhammed Ali’s family were granted hereditary right to the throne of Egypt and Sudan, although they were still ordered to abide by Ottoman restraints. The Ottoman Sultan’s local rights were not dissolved.

It was in the 1840s, due to deteriorating health and failing mental faculties, that Muhammed Ali finally retired from office. He would pass on only a year after his stepping-down, and although several of his reforms have faded into obscurity, others have structured present-day Egypt’s academic, medical, and judicial systems.

Today, he is known as the father of modern Egypt, clearing the path for its inevitable independence.

Comments (16)

[…] Muhammed Ali—the father of Egypt’s modern renaissance—was the one who solidified Egyptian cotton’s reputation. In short, before 1820, “one cannot speak about Egyptian cotton but rather about cotton in Egypt.” Egyptian cotton as it is known today originates with Muhammed Ali’s reign but continues for centuries after, affected closely by local and international political climates. It was during Ali’s era that Egyptian cotton “witnessed its emergence as a definite type among world cottons,” and became a coveted textile associated with wealth and quality. […]

[…] محمد علي: مهندس مصر الحديثة صراع أن تكوني أمًا بكفالة في مصر […]