Ten million Egyptians work abroad – half of that number work in the Gulf, bringing their home country more than EGP 460 billion (USD 20 billion) in remittances each year. Yet the Egypt-to-Gulf migration experience is far more than a statistic.

Behind every Egyptian migrant in the Gulf is an affected family, and a story with a societal impact that is often overlooked and understated.

Kharag W Al Mafrood Yaood (Being Borrowed), a creative, collaborative, self-funded exhibition by Anthropology Bel 3araby, an educational initiative founded by Egyptian anthropologist Farah Hallaba, documents the Egyptian experience migrating to the Gulf – from financial prosperity to discrimination and disassociation. In addition to the exhibition, the initiative also offered public discussions and an anthological publication.

SHOWING HOW THE GULF REALLY IS A “GULF”

“The project started with a collaborative three-month workshop earlier this year,” explains Farah Hallaba. “Some of the themes that were encountered included aspiration, social class, temporality, family dynamics, memories, home, death, and belonging – all seen through both collective and personal narratives.”

Egyptian Streets had the opportunity to enjoy the exhibition’s installations, which highlighted the distortion of time and space felt during the experiences of the migrants, many of whom felt trapped between making a living, wishing to return home, and coping with crises of identity.

Hallaba took inspiration from her own personal experiences being an Egyptian migrant in the Gulf, having spent the first 18 years of her life in Saudi Arabia.

“I reckon that this project ‘Being Borrowed; On Egyptian Migration to the Gulf’ started out of a feeling of empathy and helplessness towards my father who, until today, is still in the Gulf,” shares Hallaba.

Despite Hallaba’s personal sentiments, the exhibition itself is far from personal. Curated by art critic and academic, Farida Youssef, brings fifteen imaginative artists, all with their own personal Gulf migration story.

Through their installations, a shared and tangible experience is communicated to those of the audience who have had similar experiences, as well as those being introduced to this narrative for the first time.

One interactive installation, titled ‘Mapping Absent Memory’, allows users to drop location pins on a digital map of the Gulf, followed by typing what this location represents to their migration experience.

“I was depressed going to school every day. I had a lot of bad memories there. I kept imagining being with my Egyptian friends,” reads one anonymous user’s input. The location was Bahrain.

The map was not always negative. Another anonymous user, raised in the United Arab Emirates, pinned their old school, describing it with great joy.

“This [school] was the first place I really felt that I’m accepted and acknowledged. It was also the first time I ate fish,” reads the anonymous post.

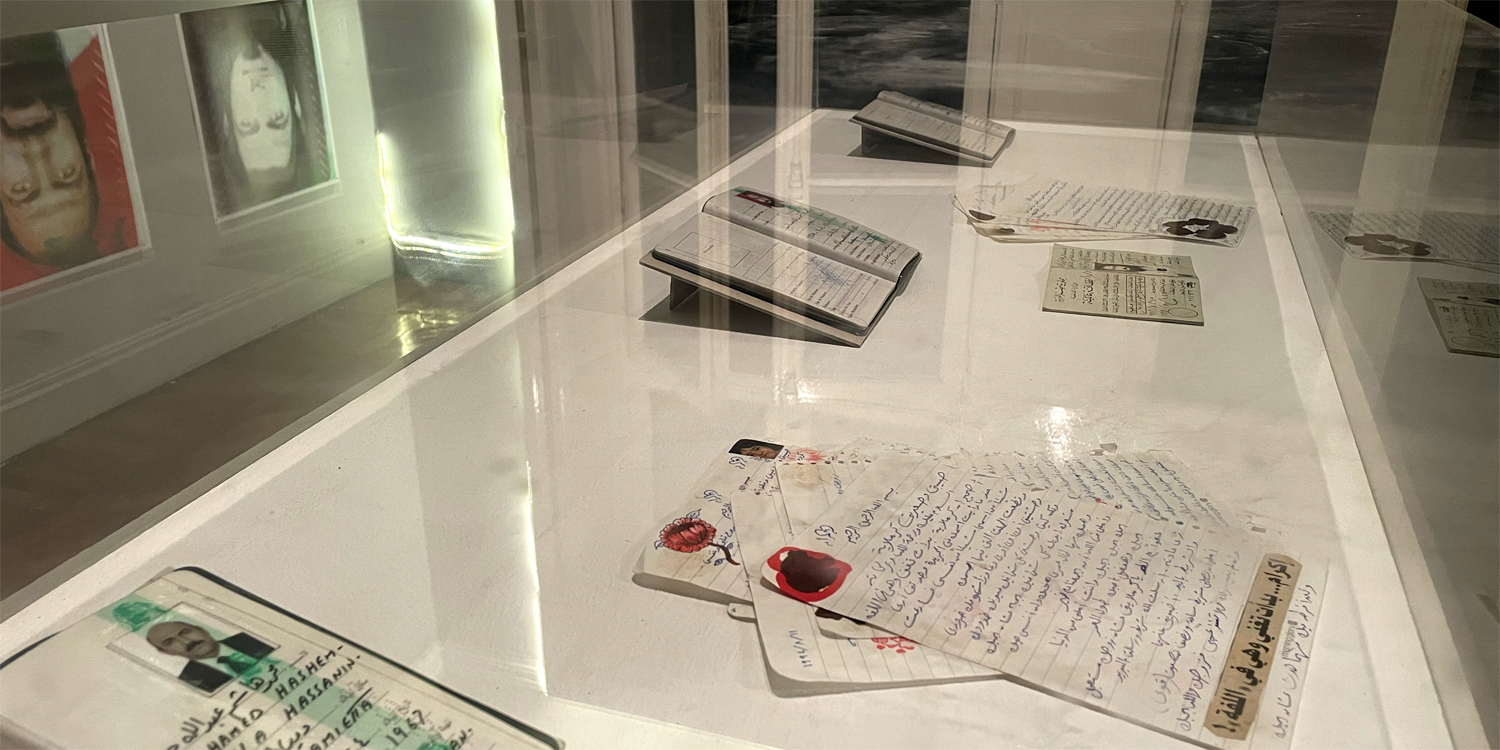

Another installation, in the form of old passports and written letters, documents the artist’s father’s experience in Saudi Arabia. It chronicles the visual transformation of the father’s identity with each new passport photo.

In the first passport photo, he dons a long, Islamic beard, and in the last photo, he embraces a mustache and a suit – documenting his transition into being a businessman in the Gulf.

Love letters to his wife, written in eloquent Arabic, are placed in an organized scatter below all three passports, allowing audiences to feel the sense of longing and love experienced through distance.

“A lot of people cried, actually, even a few the visitors that hadn’t experienced migrating to the Gulf” Hallaba points out, a sign that the exhibition brought the shared sentiments of the Gulf migration experience to life – an experience that continues to exist for many families to this day.

EGYPT’S GROWING DEPENDENCE ON THE GULF

Egypt has a “special relationship” with its neighboring Gulf countries – one that dates back to the era of eighteenth-century ruler Muhammad Ali Pasha.

As several Arab countries began gaining independence in the mid-twentieth century, Egypt was the dominant force in the region – spearheaded by President Gamal Abdel Nasser and his pan-Arab movement.

“The Arabs without Egypt are zero,” boasted succeeding Egyptian President Anwar Sadat during an interview. It was, however, during Sadat’s era that the power balance began to shift to the Gulf, as countries such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates began to reap the rewards of being oil hubs.

Amending Sadat’s tense relations with the Gulf, President Hosni Mubarak would spend his three decades of rule bolstering bilateral relations between Egypt and neighbors to the east of the Red Sea. This was also the period that witnessed droves of Egyptians seeking work opportunities in the Gulf.

Under the rule of President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi, and after having experienced popular uprisings, political turmoil, and economic hits, Egypt is becoming increasingly reliant on Gulf money – receiving around EGP 2.3 trillion (USD 100 billion) from its neighbors since 2011.

The economic boom that occurred in the Gulf during the 1970s inspired millions of Egyptians to seek opportunities with their neighbors rather than a war-torn Egypt.

With time, the dynamic between Egyptian migrants and Gulf hosts transformed into one of ‘borrowing’. Today, we see that financial dependence, and the act of borrowing, occur at a state level.

During her last visit to Saudi Arabia, Hallaba’s father informed her of his intentions to be buried in Egypt.

“This was striking to me, thinking about the trajectory of aspiration he and my mother had in the 1990s. It went from “We will go to Saudi Arabia for a few years and come back to attain a better future” to “I don’t want to be buried there,” says Hallaba.

She hopes to bring the exhibition to the Gulf itself in hopes of reaching those still moving through the migrant experience and, in turn, showing them their stories are heard.

Subscribe to the Egyptian Streets’ weekly newsletter! Catch up on the latest news, arts & culture headlines, exclusive features and more stories that matter, delivered straight to your inbox by clicking here.

Comments (6)

[…] septembre, l’anthropologue égyptienne Farah Hallaba lançait «être emprunté‘, un projet collaboratif créatif traitant de la migration égyptienne vers le Golfe. Sur la […]

[…] September, Egyptian anthropologist Farah Hallaba launched “Being Borrowed”, a collaborative creative project that addresses Egyptian migration to the Gulf. Stemming from […]