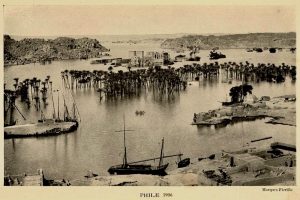

“Philae Temple,” thought to be of Nubian origin and meaning the “the temple on the island of the past,” like Abu Simbel, garnered international attention and adoration in the 1960s when a campaign was launched by UNESCO to save it from rising waters behind the newly-built Aswan High Dam.

Block by block, the temple was dismantled, moved, and rebuilt from the Philae Islands to the nearby Agilkia Island.

Its history however, extends much further beyond its rescue campaign, and serves as an example of Egyptian ingenuity and a monument to the land’s varied history to all those who visited Egypt.

Although its name’s association with the passage of time has nothing to do with its longstanding history to date, it is a well-deserved aptronym.

Before the High Dam

The first significant holy place to be built on the islands of Philae was built by Nectanebo I, one of the last native-born rulers of Egypt.

He built and dedicated the temple to the goddess Isis in the early fourth century B.C. Following him, the Ptolemies, who adopted many Egyptians deities into their pantheon, including the goddess Isis, built two-thirds of the remaining structures of Philae.

They built the Great Temple of Isis in the third century B.C., as well as the temples of Imhotep, Arsenuphis, and Hathor. Pilgrims from across the Mediterranean world would travel far to visit the Philae complex.

Following the Christianization of Egypt, two churches were built in the area between the temples of Isis and the temple of Augustus.

These churches, alongside Arab mud-brick houses from late antiquity, did not survive the rising waters and relocation of the islands’ monuments. However, Coptic inscriptions and shrines are still found around the temple complex from when the ancient Egyptian temples themselves were used as churches.

Christian crosses are often found alongside the inscriptions of the similar-looking Ankh, or the key of life, displaying how the cultural and philosophical changes of Egypt’s history are physically represented at Philae.

The Philae Temples saw the last of Egypt’s traditional cult practices. Egyptian and Christian religion had coexisted until the Byzantine emperor, Justinian I, ordered that the Temple of Isis be officially closed as part of a crackdown on pagan and polytheistic faiths.

Unlike its ‘sibling’ Abu Simbel, which was almost entirely covered by a sand dune for an estimated 2,400 years before its rediscovery by a Swiss researcher, the Philae Temple complex was not forgotten or lost to time. It saw to Byzantine, Arab, Ottoman, and Western European visitors and invaders.

It was a site of adoration and awe for the local Egyptians and Nubians for centuries, and was held as an important site throughout Egypt’s history. Famously, during the Islamic Golden Age, Philae figured as a legendary fortress in the folk-tales of One Thousand and One Nights.

The Napoleonic Invasion of Egypt began the period of Egyptomania, when Europeans became increasingly interested in ancient Egyptian history.

When visiting French soldiers saw the preceding Demotic Egyptian, Coptic, Greek, and Arabic graffitis in the area, they too carved inscriptions on the walls of the Philae Temple. More importantly, the Demotic, Coptic, and Greek inscriptions on the wall were even used during the monumentous deciphering of the legendary Rosetta Stone.

Tales of Philae Temple appearing “to rise out of the river like a mirage,” by Amelia Edwards, an English novelist and Egyptologist, brought fame to the area, and its international visitations began in full swing.

The Construction of the Dams

The completion of the first Aswan Dam, what came to be known as the Aswan Low Dam, in 1902, saw the waters of lake surrounding the Philae Islands rise significantly, and much of the temple complex was almost entirely submerged in water for ten months of the year.

Despite some alarm, the Egyptian Antiquities Service maintained and reinforced the temple in the summer months, and the waters only damaged some of the colored decorations on the walls.

The proposal of the second dam, the Aswan High Dam, however, seriously threatened the temple complex. As Philae was located in the reservoir of the first dam, but ahead of the second dam, the island would have continued to only be partially submerged. However, the new dam would have made this submersion year-round, as opposed to seasonal.

Additionally, the daily-drawing of water to power the electricity-generating turbines of the low dam would mean that the reservoir’s water level would constantly fluctuate, which, coupled with the increased water velocity in the area, would mean that the temples would gradually be completely deteriorated and destroyed.

The ongoing international campaign to save Nubian sites in the area meant that there was already much momentum to protect ancient Egyptian sites, and including Philae Temple was not a debate.

The question was how.

Research missions over the 1950s proposed building dams around nearby islands to protect the Philae islands, restore waters to pre-low dam levels, and the dismantling of the temples and raising the Philae islands themselves.

Eventually, it was agreed by the Egyptian government and UNESCO to move the temple complex to Agilkia island, 300 meters downstream. This would allow the temple to maintain its cardinal orientations, and its aesthetic would not be ruined by large waterworks projects surrounding it.

The island, however, required a substantial amount of work to prepare it for the dismantled temple. Parts of it were enlarged, and other parts were trimmed back to allow for the island to appear as if it was floating and allow the temple to reflect in the water, like the original Philae islands did.

A French institute, which specialized in photogrammetry, or the process of recording and measuring photographic data to accurately create useful models, surveyed the temple, and led the dismantling, storage, and reassembly of the temple pieces.

With the inauguration of the newly-relocated Abu Simbel in 1968, which was also threatened by the rising waters behind the Aswan dams, UNESCO and the Egyptian government were able to solicit more financial support for saving Philae Temple.

The salvaging of Philae was estimated to cost USD 14 million—around USD 100 million (EGP 3,089 million) adjusting for inflation—and a campaign to save historical sites on the Nile threatened by the dam’s rising waters “as part of the cultural heritage of the entire human race” led 23 countries to contribute to the fund. Proceeds from the exhibitions of Egyptian artifacts around the world brought the total raised to USD 15 million..

The salvaging began in 1972. First, the islands were enclosed from the surrounding waters and the water inside was pumped out. At the same time, Agilkia was being made ready. The monuments of Philae were cleaned and categorized, and the first blocks were removed from the temple complex in 1975. In 1977, the first blocks were laid on Agilkia.

Things did not go perfectly smoothly however.

Enlarging the enclosure of the islands to include the temples of Augustus and Harendotes, as well as Diocletian’s gateway, would have doubled its cost. Although the Temple of Augustus and Diocleatian’s gateway were dismantled underwater and restored on Agilkia, the Temple of Harendotes, which was already weak due after being used to provide building material for a nearby church, was found buried in silt.

Vegetation that was found on the Philae islands was planted in Agilkia, and the salvaging was announced successful.

Like Abu Simbel, Philae Temple stands as a testament to global cooperation and a love of shared history and culture. Stone by stone, for over 50,000 of them, Egypt and the world worked to save the complex. Today, as it has done for thousands of years, it draws visitors from all over the world.

Comments (2)

[…] Philae Temple: ‘The Temple of Time’ as a Marker of Egyptian History A World Court for (Some) Criminals? How the ICC Works […]

[…] Source link […]