Anyone who grew up in the ’90s knows that it was a time of its own, almost as if it stepped outside the usual flow of human history, caught between the simplicity of the past and the restless drive toward the future. Technology was still finding its feet, which meant people had more room to be present and hear each other’s voices echo across a bus or a metro, instead of scrolling through their phone screens.

And with that presence came thoughtfulness; people would often bring back gifts for cousins and grandparents after time spent abroad, simply because it mattered. In almost every North African or Arab family, there was always that one uncle or aunt who could bring everyone together in a single room, and when they started handing out gifts, it felt as momentous as a national holiday.

But maybe what was mostly significant about this time was that a new generation of North Africans and Arabs finally had the space to pause, reflect and sit with their stories of migration and identity. While older generations were focused on building something solid abroad, laying down roots and chasing stability, a new wave began to look around and look inward, noticing how the world sees them, and how they should respond.

Around that time, a wave of North African artists were starting to gain international recognition. French-Algerian singer Rachid Taha released Ya Rayah (1993), followed by Cheb Khaled’s Aicha (1996). Many songs about immigration during that period carried a somber tone, often expressing feelings of longing, displacement, or the pain of not belonging.

What was still missing, though, was a piece of music or art that approached immigration from a lighter angle, not to downplay its hardships, but to push back against racism with some humor; to use comedy and wit as a form of resistance, a way to uphold the dignity of immigrants and help them feel more rooted in their culture.

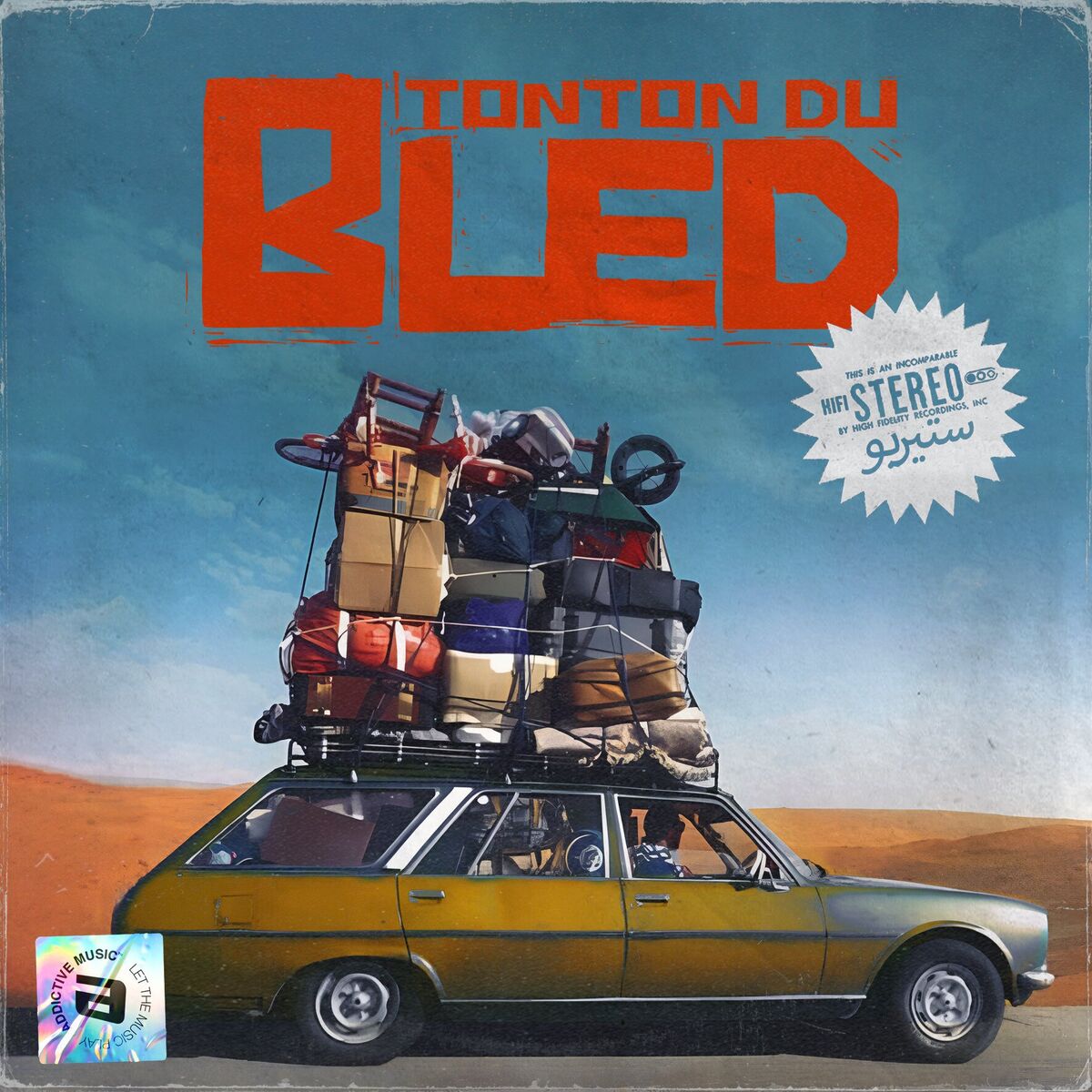

Then came Tonton Du Bled (1999) by French-Algerian rapper Rim’K and the French hip hop group 113, a track that carved out a space for North Africans and Arabs to laugh at some of their own traditions, but through that laughter, also confront the injustices they face and reclaim a sense of pride in their identity.

Comedy is not always recognized as a form of resistance, yet it often acts as a powerful counterforce, a way to challenge the world without direct confrontation. Many artists have turned to humor as a means of staring down those who have tried to marginalize them, not to mock in return, but to laugh in a way that uplifts and affirms their own strength.

It is easy to overlook comedy, as it does not quite draw attention like anger or violence, but it can be just as powerful in shifting narratives and holding onto dignity.

Using comedy as a form of resistance, the song begins with an iconic, light-hearted line: “Hey, tonton (uncle), the bags, they’re too heavy!”

Rather than beginning with a deep reflection on identity, the song starts by poking fun at a well-known North African and Arab habit: overpacking for trips; a cultural quirk so well-known that even the French recognize it. Then comes the question: why do they do that in the first place?

This is when the song moves with the beat of sharp, defiant comedy, pulling you in with humor that playfully pokes at tradition, but just as you are caught laughing at the absurdity of North Africans and Arabs, it pivots. A few lines later, the real punchline hits: the bags are heavy because Tonton is returning home with the riches of his labor abroad, giving back to his home village.

As he sings, “Since in Paris, I raided all of Tati, I’ll satisfy the whole village, even the little ones, fabric and jewelry for the newlyweds,” the music video cuts to scenes of him back in his Algerian hometown, handing out gifts to his family. Dressed in traditional attire, he sings with pride about the work he does abroad to provide for and uplift his community.

Yet, the song does not end there, because resistance is not just about bringing wealth back home or supporting your own community. It goes deeper: it is about immersing yourself in the culture, supporting local businesses, and recognizing the injustices that persist.

Later in the track, Rim’K raps lightheartedly about sipping on Selecto, a local Algerian soda, lounging by the beach, and hearing the rhythm of the darbouka, a beloved Algerian instrument. But then the tone shifts again, as he says: “I can’t close my eyes to what’s really happening, I dedicate this song to the missing, the children, and the mothers.”

It is his way of showing that migrants should not just celebrate the beautiful parts of their homeland, they should confront the painful ones too. Because being truly connected, and truly rooted in the culture, means seeing the whole story, not just the glossy postcard version.

It means recognizing that how we see ourselves is tied to how honest we are about our traditions and our reality. And the more honest we are, the more we’re able to face injustices with dignity and pride.

The song then quickly slips back into humor, especially in the chorus and the closing verses. It feels more like a back-and-forth conversation than a song with set lyrics, as the chorus mimics the way North African and Arab fathers firmly shut things down, repeating “no, no, no” as Rim’K raps about asking his dad to stay in France instead of returning to Algeria.

By the end, the migrant story takes a sudden turn and leaves us with the possibility that he might be getting married in Algeria, maybe even staying for good. It is a tongue-in-cheek twist to a song that started off focused on life abroad, hinting that maybe it is not so permanent after all, and that the return home is always just around the corner.

There is a popular saying that goes: “he who laughs last, laughs best,” often used to mean that the final laugh belongs to the real winner. Not because they have gained something grand, but because they’ve figured out how to laugh back at the world, and maybe even at themselves.

This song feels like a perfect embodiment of that idea. It reminds us not to take ourselves too seriously, to find humor in the contradictions, and in that small, fleeting moment of laughter, as the song hints, maybe we can learn to cherish our roots and our culture just a little more.

Comments (0)