By Rana Kamaly

Although many people donate money to support orphanages, that money does not actually help deal with the social stigmas or hardships that orphans face in the real world. Community Times speaks to orphans and orphanage managers about their experiences at and beyond the orphanage to see how society perceives them and the challenges they face – even long after they have left the orphanage.

According to Salwa, the manager at a girls’ orphanage, nobody knows who the parents of 99% of the children that come to orphanages are; officially, they are considered mag-hool el nassab, or of unknown origin. “We have no clue who their parents are. They are found on the streets, in front of mosques, hospitals or even in garbage cans. They are then taken to a police station. If the police cannot locate their parents, they give them a name and a birth certificate.”

She explains that the children are then taken to the social services’ bureau, which is responsible for assigning them to orphanages. She notes that, although most of these institutions are over-capacity, they continue to take in children and “figure it out” as they go along. “The number is huge; we get up to 20 kids a year if not more. It is a heart-breaking job,” she says.

According to Salwa, children taken in by orphanages are raised according to the religion of the orphanage, which is usually Islam unless the institution is connected to the church.

In many cases, the orphanage acts as a service provider or a link between donors and children. “Some places are better than others; some are hellholes with psychopaths controlling them. There is no clear procedure of rights and wrongs when raising these kids; each orphanage and supervisor disciplines the children and raises them in the way that they see fit,” she says. She explains that supervisors are rarely given guidelines to follow, meaning that the quality of supervision is inconsistent. “A supervisor might think it is okay to hit a child, or favor one over the other. This adds to psychological burden of the child, even after they leave the institution.”

She explains that, although it is a difficult situation for managers, employees, and the children, the lack of oversight by donors and the absence of clear guidelines does not help matters. “I know for a fact that some orphanages are just after the money. On the other hand, some people donate because they want to feel better about themselves, but they don’t check on the place regularly.”

She goes on: “I worked for one orphanage that used to hide supplies so that visitors would always feel that the place needs more. At the same time, they left the children to live in very poor conditions. They fired me when I threatened to tell the police or the donors.”

Salwa explains that the government plays a very limited role in caring for orphans, although they offer a fund of EGP 50 per month per child to very poor orphanages that do not receive regular donations. And while they send inspectors to regularly check the budgets and expenses, as well as to report on the facility, the supervisors, the food, etc., according to Salwa, “you can’t rely on these inspectors to give accurate reports.”

Up until recently, adoption provided children abandoned by their parents a chance to have a family outside of the orphanage, but according to Salwa, adoption rates have been declining in recent years. “In the past, social services would place a child with a married couple who could not conceive, but recently they stopped doing that because many of the parents mistreated the kids.”

With the thousands of abandoned children found and taken in by orphanages every year, Salwa wonders if it wouldn’t be better to legalize abortion and make it more accessible. “At the end of the day, it is the children who pay the price,” she says.

Unlike boys, Salwa explains that girls are often allowed to stay at orphanages for as long as they need to – usually until they get married; many of them help out or become supervisors at the orphanage when grow up. “None of the girls that I have worked with has ever asked to leave without having a plan for what they will do; after all, most of them have nowhere else to go.” When girls have a suitor and are preparing to get married, orphanages often contribute as much as possible to help the girl start a new life.

At the orphanage where Salwa works, most girls find it easy to find a job that is suitable to their education. Depending on their secondary GPA, they either go to university or college and some of them are able to land good jobs. Salwa explains that it is marriage that is often challenging for girls raised in an orphanage.

“People are wary of their upbringing and if there are any unknown genetic problems, so the girls mostly marry from other orphanages,” she says.

Mohamed, the manager at a boys’ orphanage explains that the situation is different for boys. “According to the law, it is mandatory for boys do their military service when they turn 18. After that, they find a job, get married, or rent an apartment. We try to encourage them to rely on themselves when we think they are ready. Some boys stay in touch, but others cut their ties with the institution to get a fresh start. For those who still need help, we give them EGP 50 a month and a bag of food. If they cannot survive in the outside world on their own, we allow them to come back.”

Mohamed explains that it is easier for boys to find jobs because people are more sympathetic to their situations – although certain careers are off-limits to them, including the police, the military, and justice-related jobs. “It’s ironic that military service is mandatory but that they are not admitted to the Military Academy. After all, what makes them any different from other kids?” asks Mohamed.

“In terms of marriage, it is very exceptional if a girl’s parents accepts of one of our boys, although boys with good jobs are accepted by very poor families. Others marry girls from other orphanages, but many of these marriages are disastrous and end in divorce, as any problem with the upbringing in both institutions may be doubled,” says Mohamed.

He explains that the most difficult years for most boys are their teenage years, when the children are searching for their identity and want to know who their parents are. “In the past, we used to make up stories about how they were lost or how their parents died in a car crash, but as they grew up, they wanted to look for their families and some accused us of kidnapping them. So now we try to explain the truth as gently as possible,” Mohamed says.

To better understand the lives of the boys and girls after they leave these orphanages, we spoke to three of them. Here are their stories.

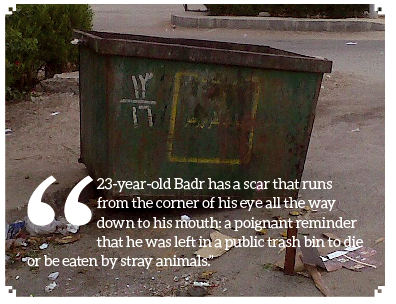

THE BOY WITH A SCAR

23-year-old Badr has a scar that runs from the corner of his eye all the way down to his mouth: a poignant reminder that he was left in a public trash bin to die or be eaten by stray animals.

After the garbage man found him, Badr ended up in an orphanage when he was just three days old, where he lived until he was 18. By then, he had finished studying mechanical services and it was time for him to leave the orphanage – not because he was forced out, but because he wanted to make space for a new kid. “I knew that at some point I would have to leave, and it was time for me to step outside and see the world as it is,” says Badr.

“Since I left the orphanage five years ago, I have met so many different people – it is like I have seen every shade of every color. While growing up, life teaches us in a very aggressive way that our past is

not something to be shared because people might look down on you, and usually, there is no reason to share it. The least that they do is whisper behind your back – if not to your face – that you are ebn haram (born of sin),” says Badr with a broken smile as he avoids eye contact.

At the public school that Badr attended, everyone was poor and they never visited each others homes, so he decided there was no point in sharing his story. “I thought I could just make up a story about my parents and live it. I knew it was going to backfire sometime because it was a series of lies,” he explains. “When I got to secondary school, another kid who had a grudge against me realized that we came and went in big groups, so he followed us and learned where we lived. The next day, people treated me like I was a different person. Some pitied me while others looked down on me, and I realized then that I had no real friends. Even the teachers didn’t try to say anything, everyone just stared while that boy laughed at me and repeated those words [that I was born of sin] in my face, over and over,” says Badr. He explains that he is sharing his story to make people realize how much words can hurt people who are unjustly judged for things that they have no control over.

Badr explains that finding a job was not that difficult, especially since most employers do not require him to share his personal history. “Believe it or not, you come to realize that everyone has something in their past to be ashamed of. The thing is, most of the opportunities that I find are at low-paying jobs. I wanted to be a policeman, but when they did a background check, they said I wasn’t suitable, even though my medical exams were fine,” says Badr, who, against the advice of his supervisor, applied to the Police Academy.

Today, Badr works at a mechanic shop and has his own apartment. He visits the orphanage to teach the children mathematics from time to time. He explains that he only shared his story with his current boss after working with him for three years. “I trust him and I don’t want to be living a lie that I really had no hand in,” he says.

And while Badr has had it rough, he knows that others have had to endure much worse. “I am not the only one with a scar; some have had it worse than me. There are kids who have lost hands or legs, and sometimes I wonder what could make a human being throw away a child. In my lifetime, I have never met anyone evil enough to do that. In the big house [the orphanage], they tried to protect us from the ugly truth by telling us different stories, how we were lost, how our family had died in a car accident, etc. After some time, we realized that we all had some version of the same story, and when we put the pieces together we thought: how many accidents can there be?” says Badr.

Badr says that he is not planning to get married at all, as he doesn’t want his children to share his social stigma; for now, he just wants to live the time he has peacefully, with no roots or branches.

THE DOUBLE CURSE

“Some kids are blessed to be in good orphanages, but others like me were cursed twice: once when their parents threw them away, and again when they grew up in an orphanage that abused them. I might have blended in with everyone else if it wasn’t for the bruises that I had from the regular beatings that I got,” says Lamsa, who spent most of her life at an orphanage.

“I am not trying to gain sympathy. The supervisors at the orphanage where I grew up saw beating as the normal way to discipline a child, and I am sure they did the same to their own children. Now I am old enough to know that all humans are corrupt in one way or another,” she says sarcastically.

Lamsa’s cynical worldview comes from the many misfortunes she endured while growing up. When she was 16 years old, Lamsa fell in love with Thabet, the son of a porter at one of the buildings near her orphanage.

“We used to walk to school at the same time on different sides of the street. I was with the other girls and he with his brother, but from time to time, we would steal glances at each other. He bought me sweets and left them at the door of the orphanage when he saw my bruises. And from time to time we would steal a talk or a walk even though it was forbidden by my supervisors,” recalls Lamsa.

She goes to explain how her dreams of love collided with the harsh reality of being an orphan when she was just 19. “One day, he wrote me a note asking me to marry him. For a moment, I forgot who I was: I was just a girl in love. But when he told his parents, they said I was bent haram (born of sin) and they refused to marry me to their son, even though they didn’t have much to offer either. When he came to ask me to elope with him, they somehow found out and told the orphanage supervisor that they saw me kissing their son and that I was trying to seduce him or something.”

Lamsa explains that, after telling the orphanage supervisor that they would never approve of the relationship, Thabet’s brother took him away and she was given a beating. “They left and took with them any dream that I had of being with him. Afterward, the supervisor asked me to leave so I wouldn’t ruin the reputation of the other girls – as if it mattered. After I left, the streets became my home. But I am determined to live as best as I can no matter what it takes. Yes, no matter what it takes. At the end of the day I will always be bent haram,” says Lamsa angrily.

When Lamsa left the orphanage, she decided to try to find any living relatives. After two years of searching, she found a family with the same name in Assiut; the family denied that she was in any way related to them, which made her realize that the story that she had been found with her name had probably been made up to make the children feel better about having no family.

“The story about them finding me with my name on my hand turned out to be a fake. It was just a nice story that a kind-hearted supervisor at the orphanage told me to make me feel better.

My name was probably given to me by a police officer,” she says bitterly. “Either way, I am glad that I left. Some of the other girls became supervisors at the orphanage and they mostly treat young girls the same way that we were treated or worse; others got married to men from other orphanages and just doubled their misery,” says Lamsa triumphantly.

THE FATHERLESS FATHER

A kindly 30-year-old who grew up in an orphanage in Nasr City, Fawzy was conscious of how difficult it would be for him to get married due to his background. “We all know that not having parents is a big issue with families when it comes to marriage, so I married someone from another orphanage. I thought someone with the same background as mine would be more understanding; I thought that we would be partners and that we would build our lives together,” he says.

Fawzy, who works as a construction worker at a company that donates regularly to the orphanage where he grew up, started his new life with a meager salary. Contrary to his expectations, however, he found that his wife Safaa was not as willing to cooperate, refusing to work and asking for things that he could not give her. “I wanted to give her everything she dreamed of, but I couldn’t afford it. We could have lived happily with my salary if she had been content,” Fawzy explains.

According to him, when Safaa left the orphanage and moved to her husband’s rented apartment, she was lured by the riches that she saw around her, and began to demand more of him.

“Two years into marriage, she gave birth to Malak, my beautiful angel, and when motherhood got too tough, she left me with a 9-month-old baby that was still breast-feeding. I don’t know where she went, she said she wanted a divorce and before I could even do that, she packed her stuff and left with all the valuables in the house. I left her divorce papers at her orphanage – I just wanted to leave all this behind me,” Fawzy says.

“Being a single parent was tough and leaving my daughter with the neighbors while I went to work was a huge burden on them, even if they didn’t say it. But people in poor places help out as much as they can, and I did all their maintenance for free as a way to repay them,” Fawzy adds with a smile.

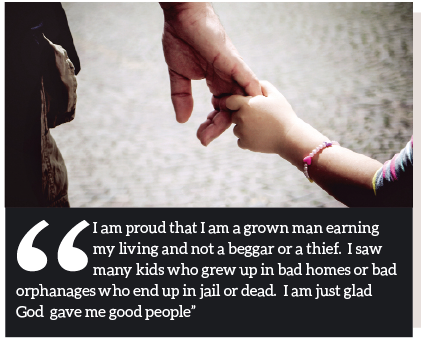

Fawzy still visits the orphanage where grew up regularly, and he speaks highly of his supervisors. He says they were better than real parents and that they have raised him in the best way possible, “I am proud that I am a grown man earning a living now, and not a beggar or a thief. I saw many kids who grew up in bad homes or bad orphanages who ended up in jail or dead. I am just glad God gave me good people,” he says.

When Malak was two years old, Fawzy married Hana, who also grew up in an orphanage. She helps with his daughter and works on and off to help out.

“I was a bit hesitant to retry the marriage experience – especially with someone else like me, but to be honest, I needed help with my daughter and Hana seemed different,” he says.

“Hana turned out to be the best thing that happened to me and I fell in love with her. She has taught me the true meaning of companionship and love, and she never made me feel like my past meant anything. She has truly saved our lives. Now we have a three year old son as well and I have never felt that she loves him more or that she treats him differently than Malak. I think she has a special bond with Malak because they are girls. Hana made our life complete and made us a real family. Now, I feel normal, like everyone else, if not even better than others,” says Fawzy contentedly.

“Family is a huge responsibility. I was always scared that I might have it in my genes to leave my kids and run, but I now know that family is God’s greatest gift to a person, and growing up without a blood bond made me cherish what I have now even more.

I wouldn’t leave my kids for the world,” Fawzy adds.

All names have been changed at the request of the interviewees..

Comment (1)

[…] Born of Sin: The Ugly Truth Beyond the Orphanage – “According to the law, it is mandatory for boys do their military … In my lifetime, I have never met anyone evil enough to do that. In the big house [the orphanage], they tried to protect us from the ugly truth by telling us … […]