From the horrors of war, to fighting repression and imperialism of all kinds, the Arab world is still in the process of disentangling itself from all roots of destruction.

Yet it will not just be achieved by superficial peace agreements or top-down economic reforms and policies, but by looking at the problem at a much deeper level and reversing the entire process step by step.

For Iman Masmoudi, a remarkable Tunisian woman who studied social and political theory at Harvard university and co-founder of the new ambitious design label ‘TUNIQ‘, the problem essentially stems from the harmful consequences of capitalism and fast fashion on local artisans and workers.

“I studied social and political theory at Harvard, and I have a lot of radical beliefs about the economy, colonization and the community, and I began to see the project as having far larger potential to model a different way of doing business,” she says to Egyptian Streets.

When she first came across an organization in India GramShree, which sells the traditional crafts of women living in rural areas and slums and uses the profits to support them with health and education programs, she was inspired to do the same in Tunisia.

“My sister Mariem, my mom, and I were traveling in Southern Tunisia and saw all the spectacular works of art that women were making in their homes, and we began to think that their art could be the source of so much benefit to them if they had a way to connect with a community of people outside of Tunisia who would buy their products and support them,” Masmoudi notes.

Initially, it was a basic idea designed to solve the problem of unemployment in Tunisia. Yet, after exploring the issue more deeply, Masmoudi realized that the issue is really more about the main ideas the world is built on regarding labour, how the economy works and how marketing should work.

The current modern economy has several harmful features that affect the local workers in Tunisia and across the world, which is exactly what the work of TUNIQ revolves around and what Masmoudi focuses on countering.

For starters, it destroys the environment that is very much essential to the work of many local people in the region.

“Desertification is spreading in Tunisia and North Africa and many people in rural areas complained to me that their crops were struggling to grow because of pollution from the spread of factories,” Masmoudi explains.

On top of that, there is the loss of human dignity, self-sufficiency and humane working conditions that work to destruct rather than help grow their skills and individuality.

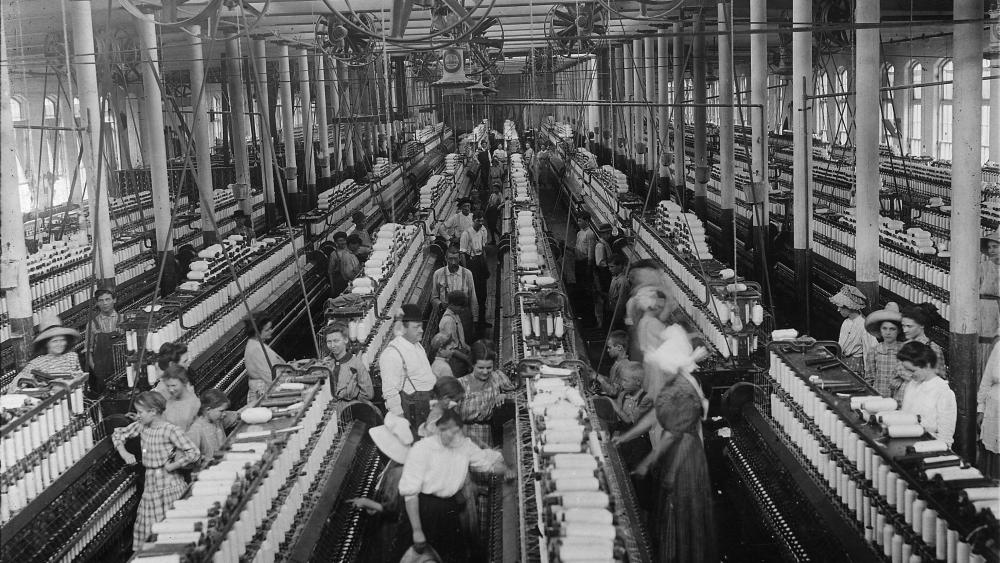

“These communities, which were self-sufficient in terms of providing their own means of income through selling their crafts and also growing their own food, are now losing all of those skills as they are forced to take factory jobs that are very low pay.”

TUNIQ is a business that introduces a new economic philosophy based on three main ethics: human dignity, labor and God’s earth.

“The pursuit of profit seemed to us, a corrupt impulse, and we wished we could help these artisans without seeking to make money off our customers,” Masmoudi says, “but, further thought and experience has taught us that of course humans traded with one another and did business long before the modern capitalist era.”

“We at TŪNIQ are inspired by the ethos of the North African merchants in the Souq. We believe that trade shouldn’t be about the relentless pursuit of profit. It should be about sharing and generating benefits for everyone.”

“Our rural craftswomen are paid high wages and are able to work from their homes and on their own schedules, as 50% of revenue goes directly into their hands, and that is before they get their share of the profits back, as well,” she adds.

The ethos of the North African merchants in the Souq is also demonstrated by how the consumers get to interact with the artisans to enrich their soul and humanity.

“Not only do we share profits, but we also share their stories with you in video features and on every TŪNIQ piece you buy. And we ask that you share photos in your pieces when you can, so the laborers can proudly see how far around the world their work has traveled.”

“Instead of the TŪNIQ logo, each of our pieces comes with a “woman’s word” on the tag such as “Munawara” (she is radiant) or “Qawiyya” (she is strong), rather than adding more TŪNIQ-specific branding, cause we’re not about that.”

The mission of TUNIQ expands even further to include the environment, which is a factor that is often excluded in the modern capitalist system.

“We must uphold the perfect God-given balance that exists within nature and not transgress the boundaries of this by taking more than what can be given and depleting natural resources which can’t be replenished,” Masmoudi explains beautifully.

“When it comes to our fabric, we are working on cutting synthetic materials completely out of our production, to reduce the growing destruction of plastic microfibers in our water systems. Our wool is local and hand-woven, and our tunics are currently a blend of organic cotton and viscose.”

“We are also trying to offer wool products that rely on natural colors produced by sheep, rather than injecting them with toxic dyes which are bad for the earth, and cut plastic completely out of our packaging and replacing it with recyclable cardboard.”

Yet Masmoudi believes that there is still a major challenge, as she realized that most people don’t really value the handmade products as she thought they would, and have become routinized and more accustomed to buy an expensive shirt from Zara or other Western brands than locally made products.

“I think this comes from a colonial legacy of undervaluing the labor of men and women of color in general and of undervaluing products that seem to have a cultural heritage outside of the West.”

“This has been a difficult challenge to overcome. How do we get people to see that these pieces are of such a higher quality and value than the fast fashion items they spend more on? It’s a deep issue.”

As the governments in the Arab world are trying to fix the local economic problems by introducing new laws and economic incentives, Masmoudi is doing it through ideas, thought and passion.

While the latter strategy may take more effort and time, tackling an issue from its roots is essentially the only way to create real progress.

“I want to be able to support every single hand-laboring artisan across all of North Africa who wants to work with us with fair and uplifting work,” Masmoudi says, with a mind full of ambition.

“Second, I would love to see TŪNIQ become a hub and an online community for anti-capitalist communitarian thought which generates new ideas for how we can build a more beautiful world together.”

‘The Oasis Journal‘, which can be found on their TUNIQ website, is open for anyone passionate about developing the world from a decolonial and communitarian perspective.

It is our role as consumers and individuals in the developing world to think deeply about how we shop and, more accurately, how we consume. Where does our money go? How will it impact the world? Why am I buying this for that price?

Acting with true conscious, and full awareness of the things around us, is what will help truly change our part of the world.

Comments (0)