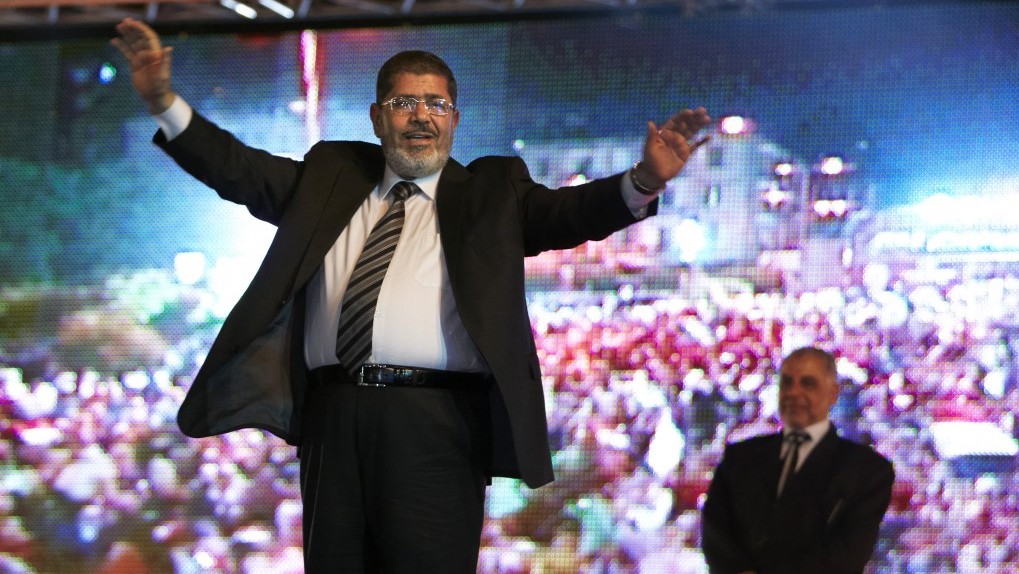

Mohamed Morsi, who died in a courtroom aged 67 on Monday, served as the fifth President of Egypt in 2012, before he was ousted following mass protests against his rule a year late in July 2013.

Morsi was born in the Sharqiya Governorate in northern Egypt on 8 August 1951, and in the late 1960s, he moved to Cairo to study at Cairo University where he earned a degree in engineering with high honors in 1975.

He fulfilled his military service in the Egyptian Army from 1975 to 1976, before earning a government scholarship to study in the United States in pursuance of a PhD in material science from the University of Southern California in 1982.

As an expert on metal surfaces, Morsi also reportedly worked with NASA in the early 1980s and helped develop Space Shuttle engines, though the extent of his work with NASA is unclear.

Life in Politics

Since the 1970s, Morsi has been a loyal member of the Muslim Brotherhood organization and he paved the way for the group to be more visible in Egypt’s government after he was independently elected to parliament in 2000.

On 28 January 2011, following the start of the January 25 protests against former President Hosni Mubarak in 2011, Morsi was arrested along with 24 other Muslim Brotherhood leaders, before escaping two days later. His escape from prison in 2011 later became one of the incidents for which Morsi would stand trial.

The Muslim Brotherhood’s political wing, the Freedom and Justice party, was founded in the wake of the 2011 revolution, and Morsi became its first president.

Elections in June 2012 brought the Muslim Brotherhood to power, when Morsi defeated former Mubarak Prime Minister Ahmed Shafiq with just 51.7 percent of the vote.

Presidential Controversies

Morsi was sworn in on 30 June 2012, and upon taking office, he mentioned that he would work to free Omar Abdel-Rahman, convicted of the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center in New York City, along with other Egyptians who were arrested during the January 25 revolution.

On 10 July 2012, Morsi reinstated the Islamist-dominated parliament that was disbanded by the Supreme Constitutional Court of Egypt on 14 June 2012, as he ordered the return of legislators elected in 2011, a majority of whom were members of Morsi’s Freedom and Justice Party and other Islamist groups.

Morsi’s later decisions took a turn against the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), which have historically held significant power and influence in Egypt.

On 12 August 2012, Morsi asked Mohamad Hussein Tantawi, head of the country’s armed forces, and Sami Hafez Anan, the Army chief of staff, to resign.

Morsi fired two more high-rank security officials on 16 August 2012, including intelligence chief Murad Muwafi, the Director of the Intelligence Directorate and the commander of his presidential guard.

Morsi also named Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who was then serving as chief of military intelligence, as Egypt’s new defense minister.

Regarding his relations with the liberals and minorities in the country, Morsi was not able to secure their support due to the persistent battle between Islamists and liberals.

The new culture minister, Alaa Abdelaziz, fired the head of the Egyptian General Book Authority and the head of the Fine Arts Council. He also he turned on Ines Abdel-Dayem, the director of Cairo Opera, by dismissing her and replacing her with the opera’s artistic director.

At the time, Nayer Nagui, a prominent Egyptian composer and musical director, accused the government of having a “detailed plan to destroy culture and fine arts in Egypt.”

Morsi also did not attend the enthronement of Coptic Pope Tawadros II on 18 November 2012 at Abbasiya Cathedral, while then-Prime Minister Hesham Qandil did.

As a supporter of the opposition forces in the Syrian conflict, Morsi attended an Islamist rally on 15 June 2013, where Salafi clerics called for jihad in Syria and denounced supporters of Bashar al-Assad as “infidels.”

Morsi announced at the rally that his government had expelled Syria’s ambassador and closed the Syrian embassy in Cairo, and called for international intervention on behalf of the opposition forces in the effect of an establishment of a no-fly zone.

The Fall of Morsi

On 22 November 2012, Morsi issued a controversial declaration, which stated that the “president may take the necessary actions and measures to protect the country and the goals of the revolution” and placed the president as the sovereign of the state, as he can “claim exception against all rules.”

Egypt’s highest body of judges decried the ruling as an “unprecedented assault on the independence of the judiciary and its rulings.”

Protests against Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood kicked off on a large scale on 27 November 2012, with clashes reported outside the presidential palace in Heliopolis as tear gas was fired at protesters who called for the ouster of Morsi and his government.

The protests, which continued into December, saw Morsi accusing opposition parties of inciting violence. A curfew was temporarily put in place as protests spread, and on 6 December 2012 at least seven people were killed and more than 600 injured in clashes between Muslim Brotherhood supporters and demonstrators.

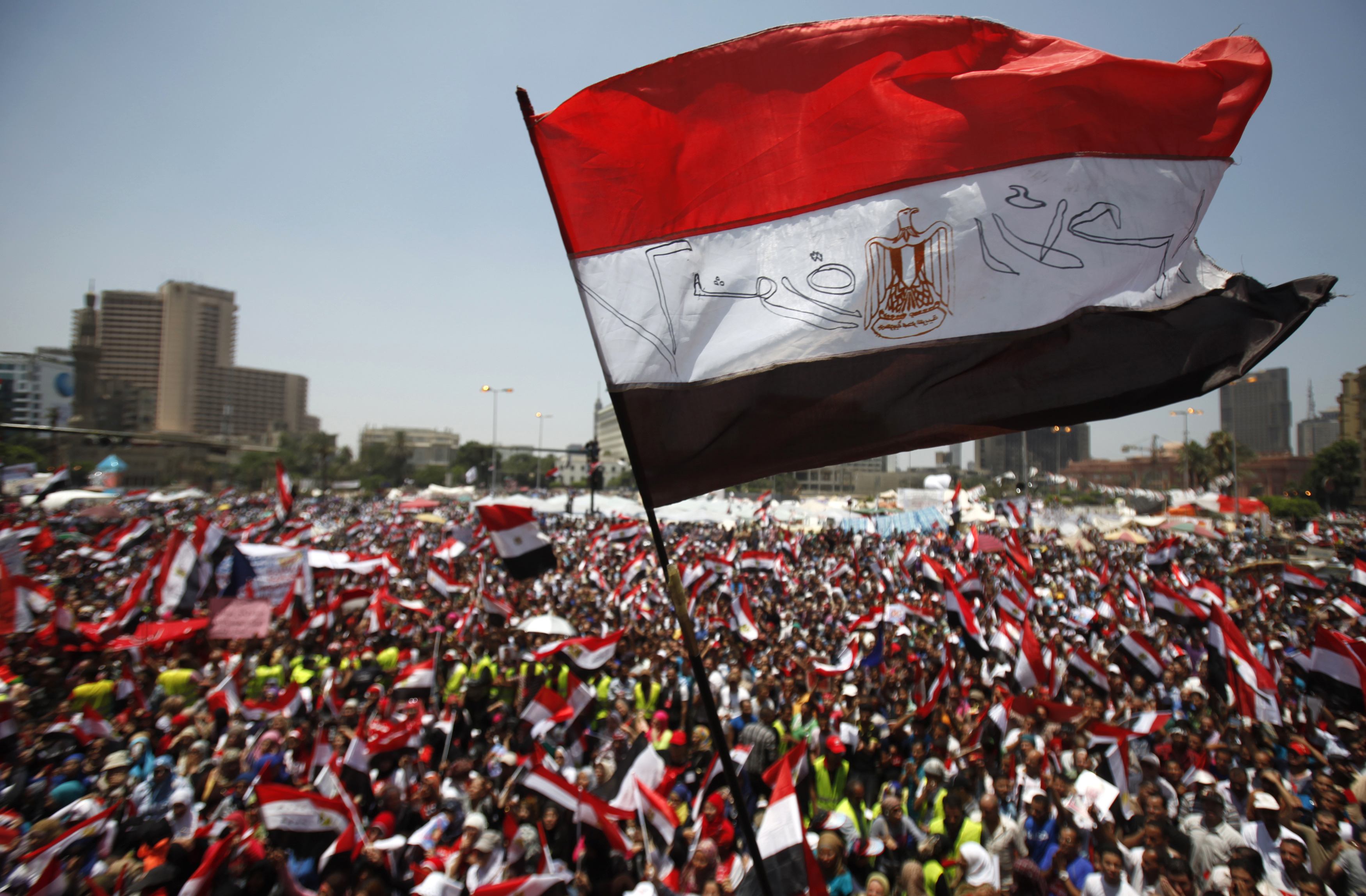

Demonstrations of varying size continued in the first six months of 2013 and a petition was started by a movement called ‘Tamarod’. Tamarod claimed to have collected more than 20 million signatures calling for the resignation of Morsi. The movement later called for mass protests in June.

A speech was held by Morsi on 26 June targeted at alleviating concerns against his rule. Aimed at reconciliation with the opposition, the speech instead caused anger and Morsi was accused of dismissing the opposition’s concerns.

On 30 June 2013, millions of people protested across Egypt calling for President Morsi’s resignation from office.

On 1 July, the Egyptian Armed Forces issued a 48-hour ultimatum that gave the country’s political parties until 3 July to meet the demands of the Egyptian people, before General Abdel Fatah al-Sisi removed Morsi from office and appointed Adly Mansour, the head of the Constitutional Court, as the Interim President of Egypt

Life After Politics

Following his overthrow, Morsi faced several charges, including for inciting the killing of opponents protesting outside his palace, espionage for foreign militant groups such as Hamas, Hezbollah and Iran’s Revolutionary Guards, and for leaking classified documents to Qatar.

Morsi first appeared in court in November 2013, where he told the judge “I am the legitimate President of Egypt” and said the court and its processes were “illegitimate.” Morsi also made reference to the Rabaa Al-Adaweya and Al-Nahda square demonstrations that were held following his ouster – and which were later forcibly dispersed – by flashing the ‘Rabaa’ hand sign as he appeared in court.

On 18 December 2013, then-Prosecutor General Hisham Barakat ordered the referral of Morsi to criminal court on charges of espionage, in a report headed “The Biggest Case of Espionage in the History of Egypt”, which stated that the international organisation of the Muslim Brotherhood was the reason behind violence and terrorism inside Egypt.

In April 2015, the death penalty was imposed on Morsi and 105 others for their role in the Wadi el-Natrun prison break of January 2011.

In November 2016, the court of cessation overturned Morsi’s death penalty on the spying charges, before imposing on him a life sentence in June of the same year for passing state secrets to Qatar.

On 17 June 2019, Morsi collapsed during a court hearing on espionage charges and later died of a heart attack.

Despite reports by human rights organisations that Morsi had been poorly treated in prison and not provided with appropriate medical support, Egypt’s Prosecutor General said that Morsi had been treated in accordance with the law while in detention and was regularly examined by doctors and provided with medical support.

Morsi was reportedly buried several hours later in Cairo in the presence of his lawyer, sons and wife.

Comments (0)