Across time, Tahrir square has been at the heart of all the political transformations that Cairo has witnessed in its modern history – from colonialism, to nationalism and independence. Since the 25 January protests in particular, Tahrir, which means liberation in Arabic, became a symbol of freedom and rebellion of the Egyptian people, and also a controversial site that could spark a lot of unrest in the region.

From west to east, the square is surrounded with one of the most historical buildings in modern Cairo. The Cairo tower, representing the nationalist period of former president Gamal Abdel Nasser in the 50s, the Arab League and the Egyptian Museum of the colonial/Ismail Pasha era and the headquarters for President Hosni Mubarak’s National Democratic Party (NDP) – all which cover the entirety of modern Egyptian history.

However, the status of this public square has changed dramatically since it was first constructed during the colonial era. It was also not intended to become historical or used for political and gathering purposes, but was originally built as a high-class residential neighborhood inspired by European urban planning and Isma‘il Pasha’s hopes of modernizing the capital after his visit to Paris in 1867.

Memories of Colonization

During Khedive Ismail’s reign, European influence was at its strongest point, and urban planning was largely constructed to reflect and mirror Western cities. After living in Paris for a while, Ismail embarked on a project to build a district later named after him – Ismailia Square – as part of his plan to modernize the city and strengthen his political legitimacy.

The square later become associated with colonization, as Gehan Selim notes in ‘Between Order and Modernity: Resurgence Planning in Revolutionary Egypt’, since British troops took over the Qasr al-Nil barracks as part of their conquest of the country in 1882.

In the early twentieth century, the Ismailia square began to have a more defined form after the roundabout was built to facilitate the new vehicular traffic in Cairo, followed by the Arab League headquarters which were built during King Farouk’s time.

Nevertheless, rebellion was still very much tied to the square’s identity, as Nezar El Sayyed, author of ‘Cairo: Histories of a City’, notes, for it witnessed the first protest against the British presence in Egypt and the colonial architecture in the country, leading to police killing two dozen Egyptians by Feb. 11, 1946.

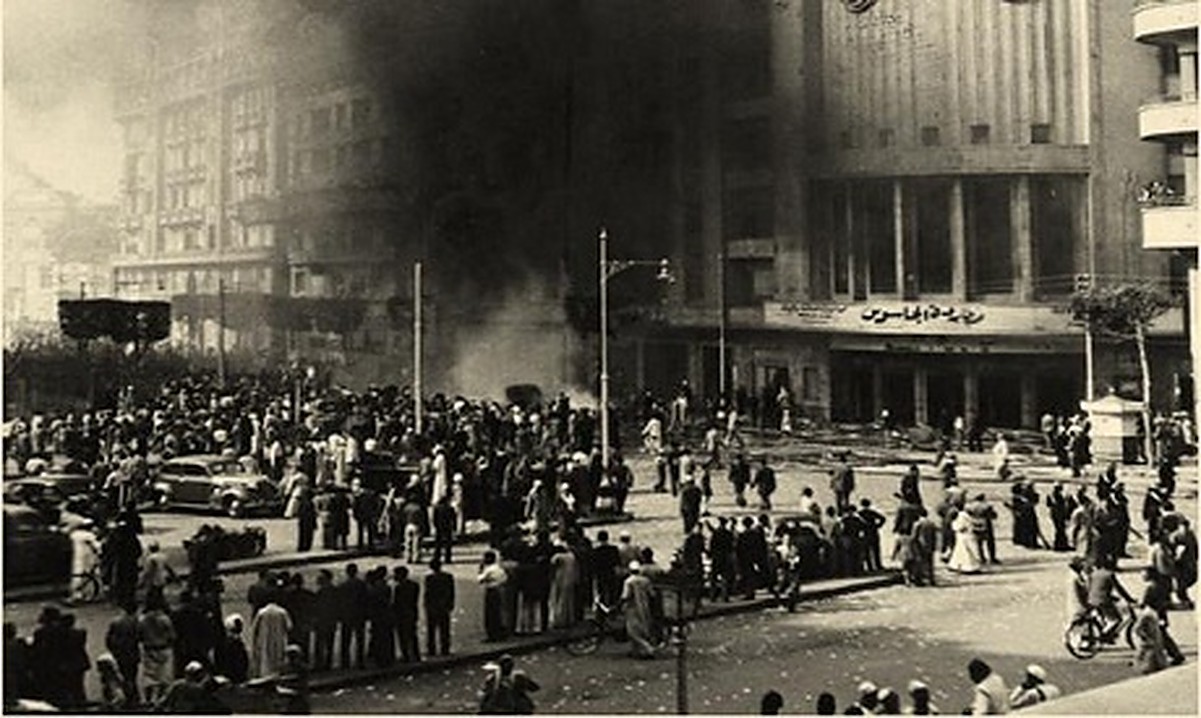

Another set of protests also broke out that resulted in the Great Fire of Cairo on Jan. 26, 1952, which affected a couple of buildings on the square. Coincidentally, the same incident occurred later in 2011 when the Egyptian people protested at Tahrir Square against Hosni Mubarak’s government.

Mohammad al-Shahed, a specialist in modern architecture, pointed out in ‘Cairo Since 1900’ that this fire marked the end of an era, and the beginning of a revolt against colonial architecture with a commercial and leisure purpose.

From Ismailia Square to Tahrir Square

Following the rise of Gamal Abdel Nasser, the new government issued a decree changing the name of the square from Ismailia to Tahrir to mark the departure of the British from Egypt.

According to Nasser Rabbat, the square “evolved to reflect the changing political ideology of the government after the revolution,” and became a symbol of the liberation of Egypt.

Gehan Selim adds that this change of ideology also reflected a change in the architecture, with the construction of the Cairo tower that carried styles of the pharaonic antiquity as well as nationalist symbols like the eagle at the entrance, all pointing to the new era of the new republic.

Later, the Hilton Hotel was built on the site of the former English Barracks, and was renovated to now become the Ritz-Carlton. Next to it was the headquarters of Nasser’s Arab Socialist Union, which was inherited by Mubarak’s National Democratic Party.

With the era of infitah (open-door economic policy) during Sadat and Mubarak’s time, the square reflected the signs of globalization and consumer culture advertising billboards and fast food chains, before it became another famous site for rebellion.

Several other protests and gatherings followed, such as the marches at the funerals of ‘Abdel Nasser and Um Qulthum, the Iraq war protest in 2003 against the American invasion, as well as early protests connected to the Egyptian Movement for Change – Kifaya.

Following 2011 and 2013, the Tahrir Square became the center of change and of renewals of political ideology, reflecting very well the era of each regime Egypt had witnessed. It represents the heart of a vibrant city, the voices of a people, and the hands of the government it is operating under.

Comments (0)