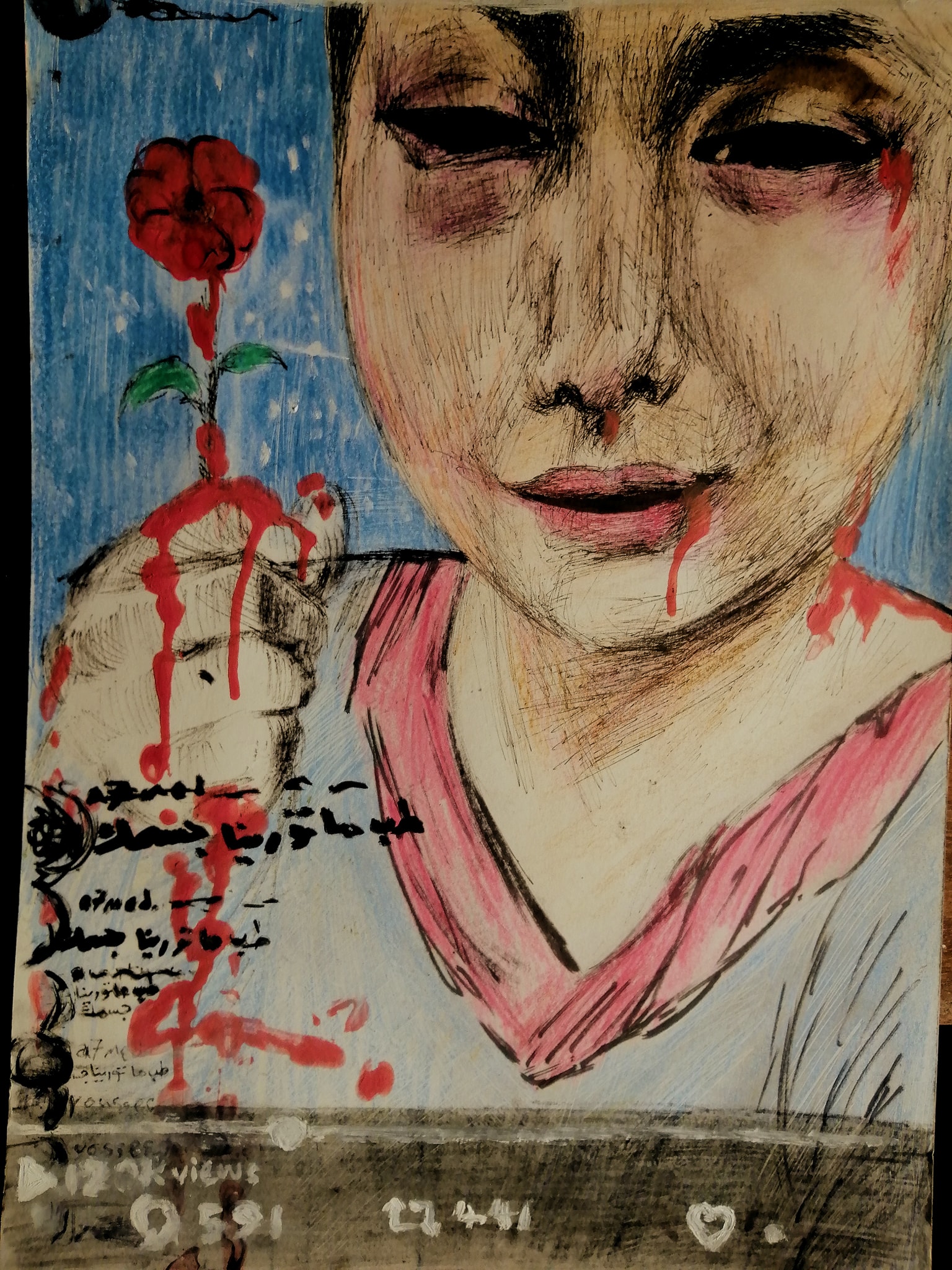

Few cases have captured Egypt’s public imagination in recent months like the Menna Abdel Aziz affair. Once an obscure figure on social media, the 17-year-old burst into the country’s mainstream consciousness when she publicly accused 25-year-old Mazen Ibrahem of raping her in May, while his accomplices beat her and filmed the assault.

Following social media uproar, where reactions ranged from solidarity to victim blaming, Abdel Aziz issued a fearful retraction in a social media video post where a man could be heard giving her directions.

A few days later, the culprits were arrested and a forensic exam would later confirm Abdel Aziz’s initial rape and assault allegations, but by then, this assertion of wrongdoing was devoid of any vindication for the victim who now faces charges of “misusing social media, inciting debauchery and violating Egyptian family values,” according to Al Masry Al Youm.

The prosecution ordered the detention of Mazen Ibrahem, Bassam Hanna, Shaimaa Shaker, Fatma Shaker, and Mohamed Hamdy, as well as the receptionist at the hotel where the assault took place who face charges of rape, conspiracy to commit kidnapping, robbery, assault, using drugs, invasion of privacy and blackmail, and violating Egyptian family values, among other things, according to the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR), the organization that represents Abdel Aziz in both cases.

A Dangerous Precedent

“The fact that she is charged is a dangerous enough precedent … Why would a person who hasn’t done anything, find themself all of a sudden a defendant? They were going on about their life and someone directed violence against them. It may be read as a message to women not to speak up when they are victims,” says Lobna Darwish, EIPR’s gender and human rights officer.

Prosecutors haven’t disclosed the details of their investigation into Abdel Aziz, but her arrest and the charges against her were initially prompted by her appearance, choice of dress and social media content, which authorities have deemed sexually suggestive and socially subversive, according to local media.

At first glance, Abdel Aziz falls at the cross-section of victimhood and criminality the likes of which the world hasn’t seen since the Patty Hearst trial, but even the American Heiress’ saga pales in comparison to the complexity and layered legalese of Abdel Aziz’s case.

According to Darwish, the charges against Abdel Aziz were brought under provisions of Egypt’s anti-cyber crime law, which was ratified by President Sisi in August 2018. Aimed at preventing the dissemination of extremist ideology and protecting state secrets and classified information, the controversial law authorizes blanket surveillance of Egyptian data subjects, censorship and internet filtering, among other things.

“When the cyber crime law was written, it included [a] very, very, very vague sentence regarding ‘family values’ … the law has to be precise about what constitutes a crime, this is a general legal principle, [it shouldn’t be] subject to anyone’s interpretation, not even a judge’s,” Darwish tells Egyptian Streets. “What are the perimeters of these family values? What should the length of my skirt be? It is a bit random and all over the place because families differ from one another, so one’s personal reference of what is wrong and what is right cannot be the standard, the reference should be the law and it should be very clear on what the crime is.”

Vague Legislation

This is not uncommon in Egyptian legal tradition. Under civil law, the legal system adopted in Egypt, judges rely primarily on statutes and legal codes when rendering a judgment, as opposed to legal precedents in the common law tradition, which allows for greater judicial creativity. Legal codes often lack specificity and are usually more pliant to address and offer legal remedies to a wide range of issues and scenarios.

However, using ambiguous and vague language in legal texts is generally considered an obfuscationist practice tantamount to entrapment because accessible and readily understandable laws are an inalienable, natural human right. “A citizen, when being tried, should know what they are being judged for. But also, as a citizen who doesn’t want to be criminalized, I should know what to avoid doing. Now, when we go on Instagram, we don’t know what to share and what not to share,” Darwish remarks. “[The law] should be very clear on what the crime is so I can avoid doing it if I want to protect myself from being pursued.”

Prosecutorial Misconduct

Additionally, the authorities’ handling of the case was marred by procedural irregularities and gross prosecutorial misconduct. In addition to basing the charges against her on the culprits’ statements, prosecutors infringed on Abdel Aziz’s right against self-incrimination in order to collect additional evidence against her.

“The charges against Menna were partly based on an [eight-hour] interview with her as a victim …She said everything about her life, recounted details about the attack against her and the circumstances in which it happened in the hope of getting restitution,” Darwish explains. “If I am being questioned as a defendant, however, I have the right to remain silent and not volunteer incriminating statements. It is like she has been dragged into giving evidence against herself—assuming these are even crimes to begin with.”

The mishandling of investigational procedures may have also given Abdel Aziz’s rapist and his accomplices an unfair advantage in the state’s criminal case against them precisely because, as defendants, they can assert their right against self-incrimination.

Did The Prosecution Abuse Its Discretionary Powers?

This legal double bind that Abdel Aziz now finds herself in should be avoided at all cost, according to Darwish. And while redressing the flaws in Egypt’s legal framework, which fails to uphold constitutionally-protected civil rights, such as freedom of expression and personal liberty, remains one of the biggest issues underlying Abdel Aziz’s case, immediate legal remedies can go a long way in righting the wrongs done to her.

“It is within the prosecutor general’s powers to issue [internal guidelines and policies], instructing prosecutors that in sexual violence cases, the victim cannot be charged,” she argues.

Instead of dropping charges against Abdel Aziz altogether, prosecutor general Hamada El Sawy gave the Ministry of Social Solidarity physical custody of Abdel Aziz for the remainder of her detention pending investigation and trial, confining the victim to a rehabilitation shelter for women victims of violence.

The move was hailed as a step in the right direction by the National Council for Women (NCW), but according to Darwish and Abdel Aziz’s defense team, these measures are still lacking.

“We are happy that the prosecution reached out to the Ministry of Social Solidarity, but they should enlist their help as a public service provider,” she says. “Services given to victims and survivors of gender-based violence should always remain services, they can’t be turned into something punitive. A shelter for battered women can’t be used as a detention center. This is a dangerous precedent because we are telling women to turn to the Ministry of Social Solidarity if they experience violence, they can’t be given the impression that this is a detention center. This is a place that women go in and out of voluntarily to receive services from the state that are my rightfully mine.”

The prosecution’s use of its discretionary powers to place Abdel Aziz in the custody of a shelter for women victims of violence may seem lenient considering that the alternative is pretrial detention in jail. It isn’t.

“In accordance with Egyptian law, pretrial detention is the exception, not the norm. As long as the accused hasn’t been tried yet, they should remain free, unless their freedom constitutes a danger [to society or their alleged victims] … but the law gives the prosecution and the judiciary the right to choose between pretrial detention and alternative measures, such as house arrest,” Darwish explains. “In Egypt, in the last couple of years, there has been an [abuse] of pretrial detention, especially when it comes to political cases, but also in criminal cases, as we can see. Everybody gets pretrial detention and this is not normal.”

A Pattern of Over-criminalizing Women

Abdel Aziz is just one of many women currently subjected to the state’s arbitrary power due to vaguely worded laws and an unwillingness by the prosecution to use its powers to offer immediate and much-needed legal remedies to protect victims of gender-based violence.

Her arrest came as part of a broader campaign targeting visible women on social media on similar charges for their appearance, dance moves and/or uncorroborated claims of undefined immoral acts, most notably Haneen Hossam, Mawada El Adham, Manar Samy, Renad Emad and bellydancer Sala El Masry who was recently sentenced to three years in prison for inciting debauchery.

The 2018 cyber crime law may have laid the groundwork for this ongoing morality campaign, but Egypt’s justice system’s failure to protect civil rights and liberties for women, LGBTQIA individuals and vulnerable groups predates that. The term debauchery in Egyptian law traces its origin back to the law no. 10/1961, which was intended to combat sex work.

“There is an expansion in criminalizing people and using, almost stretching, the meaning of the law … This is particularly applicable when it comes to debauchery cases. In debauchery cases, we see a clear pattern of criminalization—especially against gay men and trans women who are charged for consensual, non-commercial sex, even though Egyptian law doesn’t criminalize, theoretically, sex between men,” Darwish remarks. “When the case is presented before higher courts, the person is usually acquitted, but in the meantime, they have been incarcerated and their life has been destroyed because of the stigma.”

This overcriminalization was apparent in the prosecution’s handling of the Cairo Bathhouse case, in which 26 men suspected of being gay were accused of inciting debauchery and later acquitted. It is clear that the law and its application are divorced from reality because the women and gay men who are often arrested and detained on the suspicion of engaging in commercial sex are usually indigent or are otherwise socio-economically vulnerable.

“There is a class angle to it. We all know that there is a very powerful class system that determines what is right and what is wrong. We are not saying everyone should be criminalized over details pertaining to their intimate lives, on the contrary, we are saying that everyone has the right to privacy. It is a [constitutionally protected] right, this doesn’t concern anyone, these are individual liberties,” Darwish says.

Can Egypt’s Justice System Protect Women?

This new legal tone may reflect the rise of a new Egyptian conservatism designed to subsume or pander to any lingering Islamist or theocratic aspirations now that the Muslim Brotherhood is officially considered a terrorist organization. Regardless of the policy objectives, however, the resulting justice system is becoming increasingly socially authoritarian, paternalistic, and, judging by this recent wave of arrests against visible women, one that only holds its female and LGBTQIA subjects to these puritanical standards.

As Egyptians mobilize in solidarity with the alleged victims of Ahmed Bassam Zaki who has now been accused by upwards of 50 women and girls of sexual harassment, assault, rape, and sexual misconduct against minors, it is important to understand the existing legal framework and the extent to which Egypt’s justice system is equipped to help them attain that justice. A high-profile case like Abdel Aziz’s offers a blueprint for how the country’s justice system deals with survivors of sexual violence who brave immense social pressures to come forward, and it is sadly not a very promising one.

“What did Menna do? What started this whole thing? Why is Menna charged right now? It is because she went out in a video asking society and the state to protect her. If she had stayed silent, none of this would have happened,” Darwish says.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that Zaki’s victims will be met with the same hostility by the prosecution, but it speaks to the hefty price women must pay for justice and the legitimacy of their misgivings about our justice system.

“When the system [treats survivors] with the sensibility required in cases of sexual violence, people trust the system and come forward and we are able to offer them more protections,” Darwish explains. “It is in the public interest that victims [of gender-based violence] trust the system.”

Comments (69)

[…] Egypt, teenager Menna Abdel Aziz used social media to ask for protection after a sexual assault. She was arrested on a variety of […]

[…] Hossam, Mawada Al Adham, Menna Abdel Aziz, Sherifa Refaat and her daughter Nora Hisham (also known as Sherry Hanem and Zomorroda, […]