Very few have not heard of them, for the Mamlūks are a daunting, elusive non-elite that demarcated Egypt’s medieval years, defining the era with prolific intent. Their story is one of cultural dysphoria and blood, of how men once delegated to the battlefield overthrew their Ayyubid masters, the Mongols, and European Crusaders in a fell swoop that birthed a three-century reign over Egypt.

As a term, mamlūk bears a simple linguistic meaning: ‘one who is owned.’ Granted context, it’s an expression that connotes “subordinance, obedience, and servitude.” The Mamlūks were not native to Egypt or Syria; they were brought in from Qipchak Turkey, Central Asia, and Eastern Europe by caliphs. Bahri Mamlūks were southern Russian in origin, while the Burgi were Circassians from the Caucasus.

At their most elemental, Mamlūks started off slave-soldiers as per a 1977 JSTOR article by academic Stephen Humphreys; yet they became indispensable to Muslim armies and Islamic civilization at the time. The practice itself surfaced in Baghdad, Iraq, under the command of Abbasid Caliph al-Mu’tasim around the ninth century AD, and spread rapidly across the region soon after. Boys as young as 13 were taken from areas north of the Persian empire to be employed as ghulams (bodyguards) for men of high standing. Additionally, they would be tasked with enforcing the rule of their given caliph or sultan as far afield as Andalusia (Spain).

Under new masters, they were “manumitted [from traditional slavery], converted to Islam, and underwent intensive military training,” according to a History Today article by James Waterson.

Inevitably, and some scholars argue invariably, the Mamlūks exploited the military power invested in them to usurp power and seize control over legitimate political authorities. In a poetic swing of fate, the Muslim world fell face-forward into the arms of Mamlūk generals directly after al-Mu’tasim’s reign; as military men, they were able to murder amirs (princes) and caliphs with impunity, and by the early 13th century, they succeeded in establishing dynasties of their own.

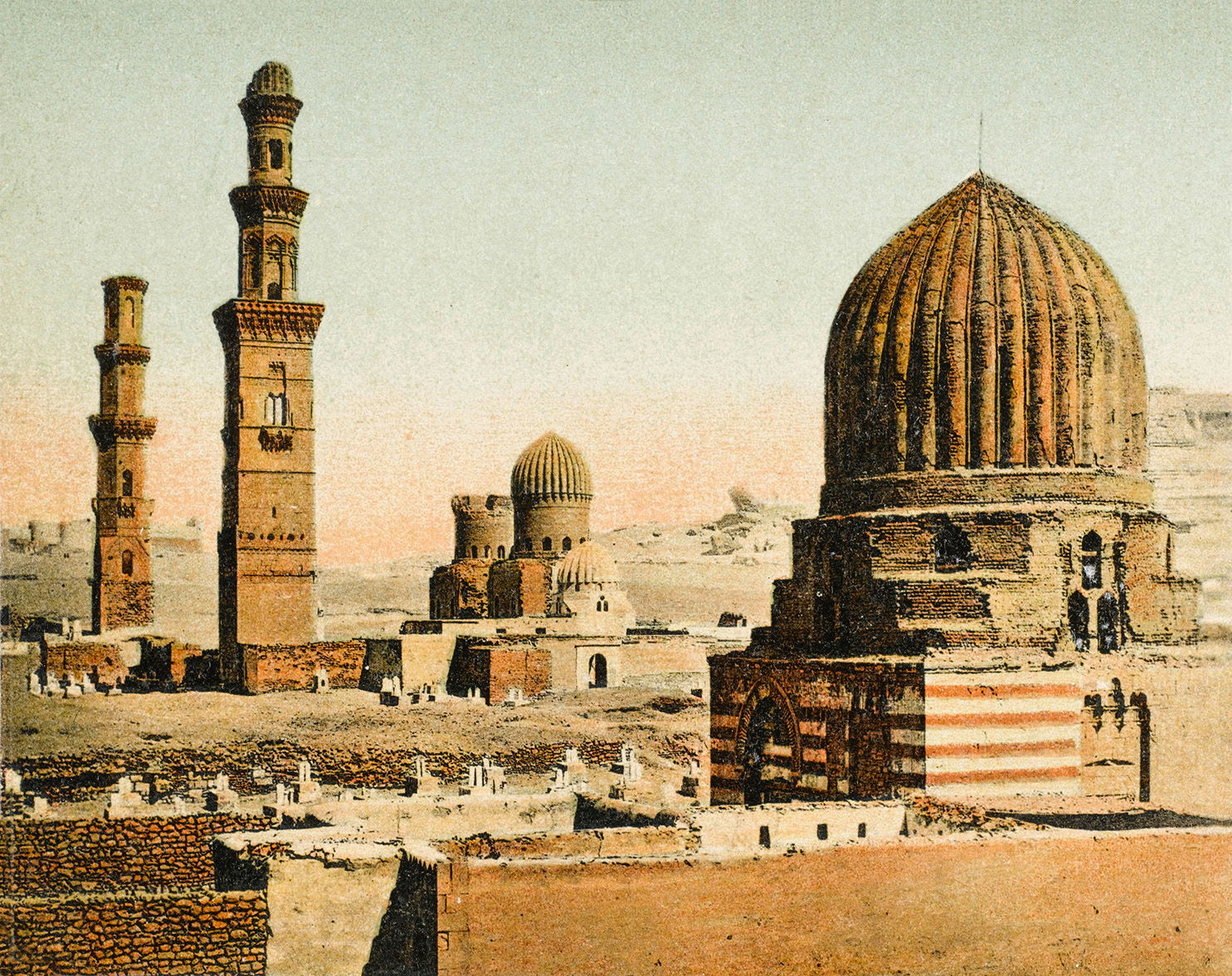

From a nameless army to amirs, the Mamlūks ruled over Egypt and Syria for three centuries, taking seat in 1250 and later overthrown by Ottoman ruler Muhammed Ali in 1517 AD. Many Mamlūk sultans went to great lengths to rid themselves of their histories as slaves, often associating with established dynasties or claiming exalted origins. However, the era was deeply documented by both Muslim and non-Muslim scribes and archivists, leaving little room for reasonable doubt as to who they were.

A famous, and “strikingly original” historian still cited today is Ibn Khaldūn, who was considered the “greatest Arab historian,” developing one of the earliest nonreligious philosophies in history.

Modern-day scholars divide the Mamlūk reign into two stretches: the Bahri period (1250-1382) and the Burgi period (1382-1517); it is universally agreed that the dynasty peaked during the Bahri reign, and proceeded to deteriorate during the Burgi sultanate. Still, both boasted general, if not shared, achievements, including the expulsion of remaining crusaders from the Levant, and triumph over the Mongols in Palestine and Syria.

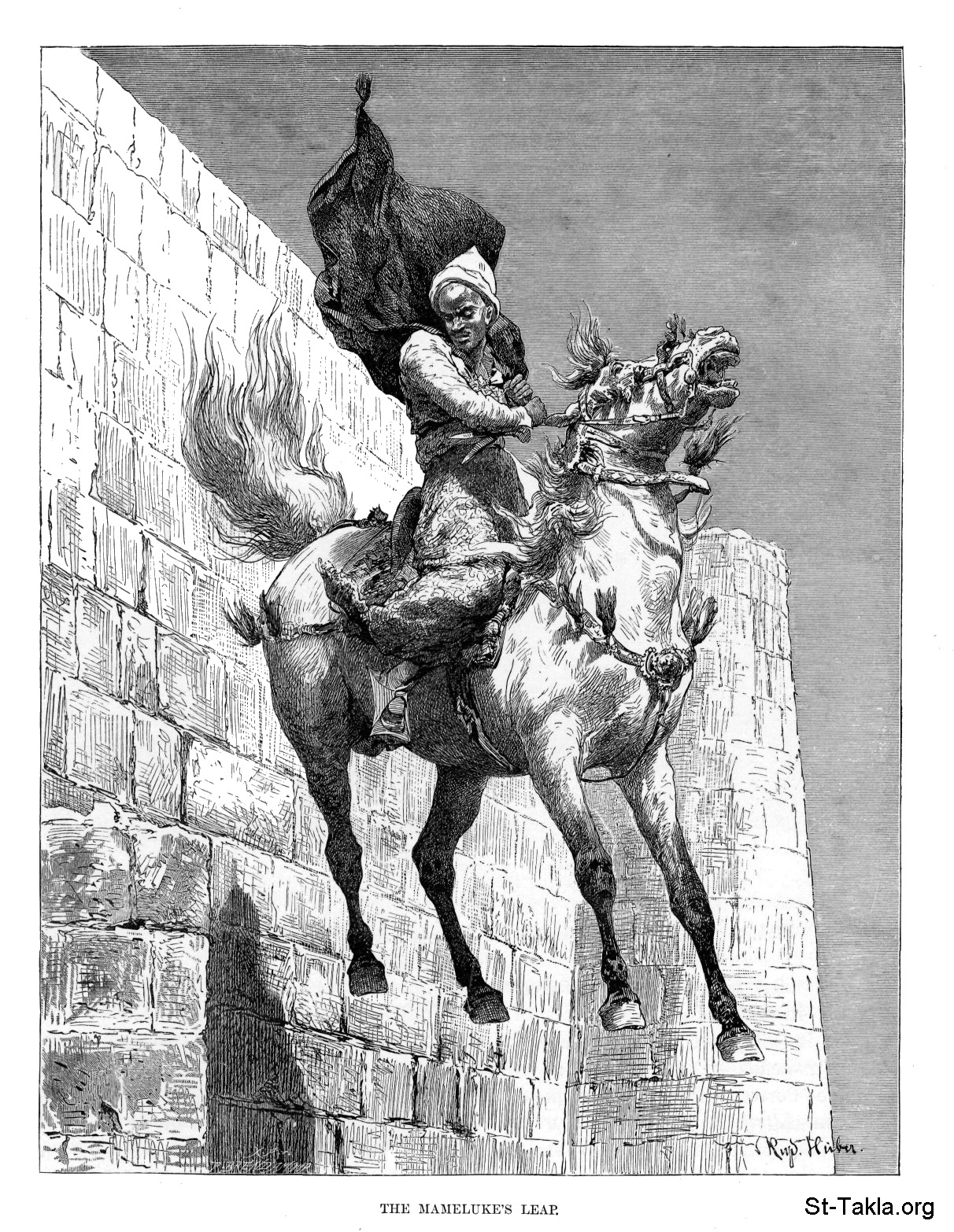

Though their successes came to a gradual, gory halt. After continuous losses to the Ottomans towards the end of their reign, and a violent massacre led by Muhammed Ali, the Mamlūks’ sultanate was effectively destroyed. Still, the Mamlūk class remained intact in Egypt for some time after, and managed to establish autonomy as a military faction within the Ottoman empire.

Their complete fall came with Napoleon’s grand, and often glorified short-stay in Egypt. By the late 18th century, the Mamlūks were no more. Though it is safe to say, by sword and sultanate, the Mamlūks have helped create the image of modern Egypt—for better or worse, for glory or for greed.

Comments (3)

[…] والرحمة. الرافعات لتقبيل يده. على تلك الإشارة ، فإن المماليك […]

[…] detailed in smile and courtesy, and with grace, cranes to kiss his hand. On that signal, the Mamlūks […]