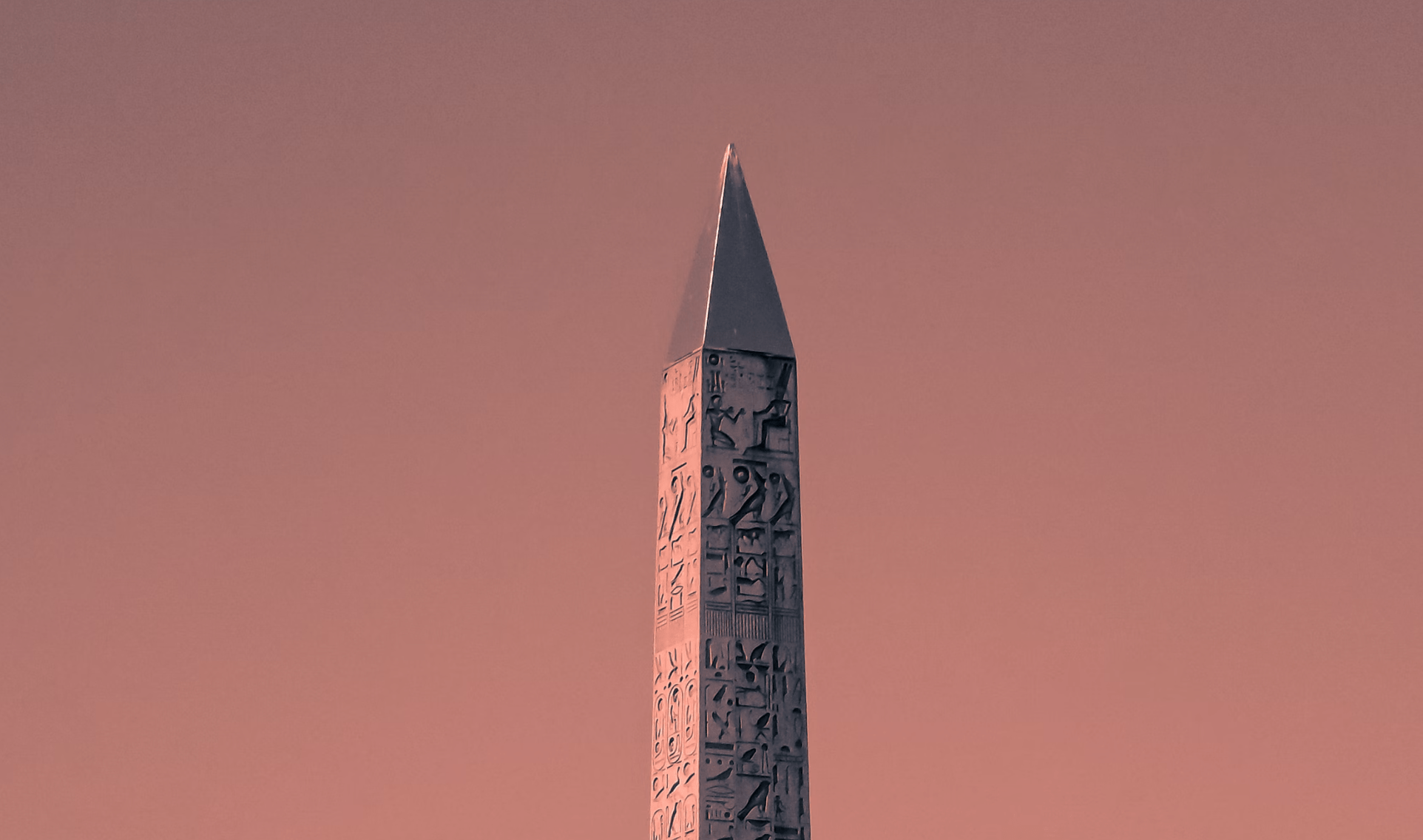

Looming over Paris is the oldest monument in France: one of two Luxor obelisks meant to stand in Karnak. Across the channel, in England, another obelisk needles a cloud-heavy skyline. In Washington DC, an obelisk sits right across from the country’s political epicenter—the White House. It seems that, of all Egypt’s enduring symbols, the obelisk has found a seat in many countries over the centuries.

For so long, “the obelisk [has] been admired and copied in various cities of Africa, Asia, and Europe” writes scholar W. R. Cooper in ‘A Short History of the Egyptian Obelisks’ (1877).

This phenomenon of “obelisks in exile” has been dated back to the era of ancient Rome, where the fascination with Egyptian symbology was key to the marriage of cultures. Numerous Egyptian obelisks were expatriated to Europe during the reigns of Augustus – a “self-styled Pharaoh” – and Theodosius, as early as 10 BC and 30 BC with Rome’s taking of Alexandria.

However, despite its ubiquitous nature, the real purpose of the obelisk has been lost to textbooks and relegated to libraries.

What is an obelisk?

An obelisk, or a tekhen, is “a monument composed of a singular quadrangular upright stone” with four faces inclined towards one another. Its peak is tapered inwards and cupped in either gold or bronze, and its height no less than ten diameters with a square base. Much like the monuments seen crowning foreign cities, Egyptian obelisks are traditionally composed of granite or hard sandstone—elements one can cut cleanly and polish. Though many took the form of red granite in particular, for the symbolic association with the sun.

Out of the forty-two obelisks known to exist, twenty-seven are carved out of the red granite of Aswan.

Obelisks were generally used as honorific gifts to sovereigns, and erected in their honor: a “direct homage of the Pharaoh to the god.”

Few obelisks were dated, and the inscriptions on them were considered monotonous; they were often detailed with official epithets and magniloquent titles. Still, the structure itself took a substantial amount of time to construct and deliver. Oftentimes, an obelisk started by one king would be completed by another, decades after.

Much like the pyramid, the obelisk is a solar emblem significant of the rising sun, and solar deities in ancient Egyptian religion. One obelisk, known as the Unfinished Obelisk, is a popular tourist stop today in Aswan.

“Obelisks in Exile”

Today, these lithe pillars of stone are inherited by the world en masse; cultures have developed obelisks independently, used them as symbols of intellect and power, and showcased them in the center of world capitals. From Italy’s Piazza Navona to Cleopatra’s Needle in England, three is no shortage of Egyptian obelisks scattered across the world.

Despite seemingly benign, however, the exportation of authentic obelisks – as well as their replication – is embedded in imperialistic narratives; be it Roman or generally Western, the practice has been placed under fire by scholars for decades. It contributes to a wider, more damaging paradigm: “Egypt of the West,” wherein Egyptian symbolism and heritage are appropriated and reimagined to fit Eurocentric ideologies.

Egyptian Egyptologist and scholar Fekri A. Hassan describes the phenomenon of erecting obelisks worldwide as a “cannibaliz[ation] of other civilizations” by colonial powers. He argues that the appropriation of obelisks is yet another way of canonizing world hegemony and legitimizing their rule and that such innate, intimate symbols must be managed differently in a globalized world.

Wanting to reassert its sovereignty over its own history, Egypt, too, erected one of its obelisks in Tahrir square in February 2020. Still, it’s pivotal to note that scholars have documented the risk of decay when obelisks are inserted into modern cityscapes, with a particular dedication to the deterioration of the Washington monument.

Though the ethics of true ancient obelisks—or obelisks of any kind— residing outside of Egypt remains highly debated, there is little doubt that the symbolism has long since graduated from the worship of a sun-god; these monoliths have become part of skylines worldwide. From the fall of Egypt to Rome, the obelisk has taken on a life of its own—for communities, kings, and cults alike.

Comments (2)

[…] المسلات في المنفى: أخلاق المسلات في الخارج […]

[…] المسلات في المنفى: أخلاق المسلات في الخارج […]