Decked on the shimmery banks of the Nile are a line of wooden houseboats – two-storey structures that constitute a safe space for their inhabitants and visitors alike – that are tethered to shore by ropes. They are unable to move on their own, but they stand as architectural visions akin to a gouache painting. These houseboats are a comfortable space to unwind; a tranquil escape from the clamorous city of Cairo.

Stretching along the banks of the Nile from Abbas Bridge down to Imbaba, and from the west side of the Rhoda and Zamalek islands, the houseboats that were once an eminent part of Egypt’s history, are threatened with demolition.

As the sounds of hammering and splintering continue, the residents and admirers of the houseboats have called the attention of the media, seen in the urgency of international and national news coverage, campaigns, and online petitions. Despite their best efforts to raise noises to halt the peremptory decision of destruction, the residents at risk of being evicted from their homes have experienced electricity and water shutdowns, leaving them to their last resort of emptying the only homes they know.

THE PAST: a cultural legacy on the brink of extinction

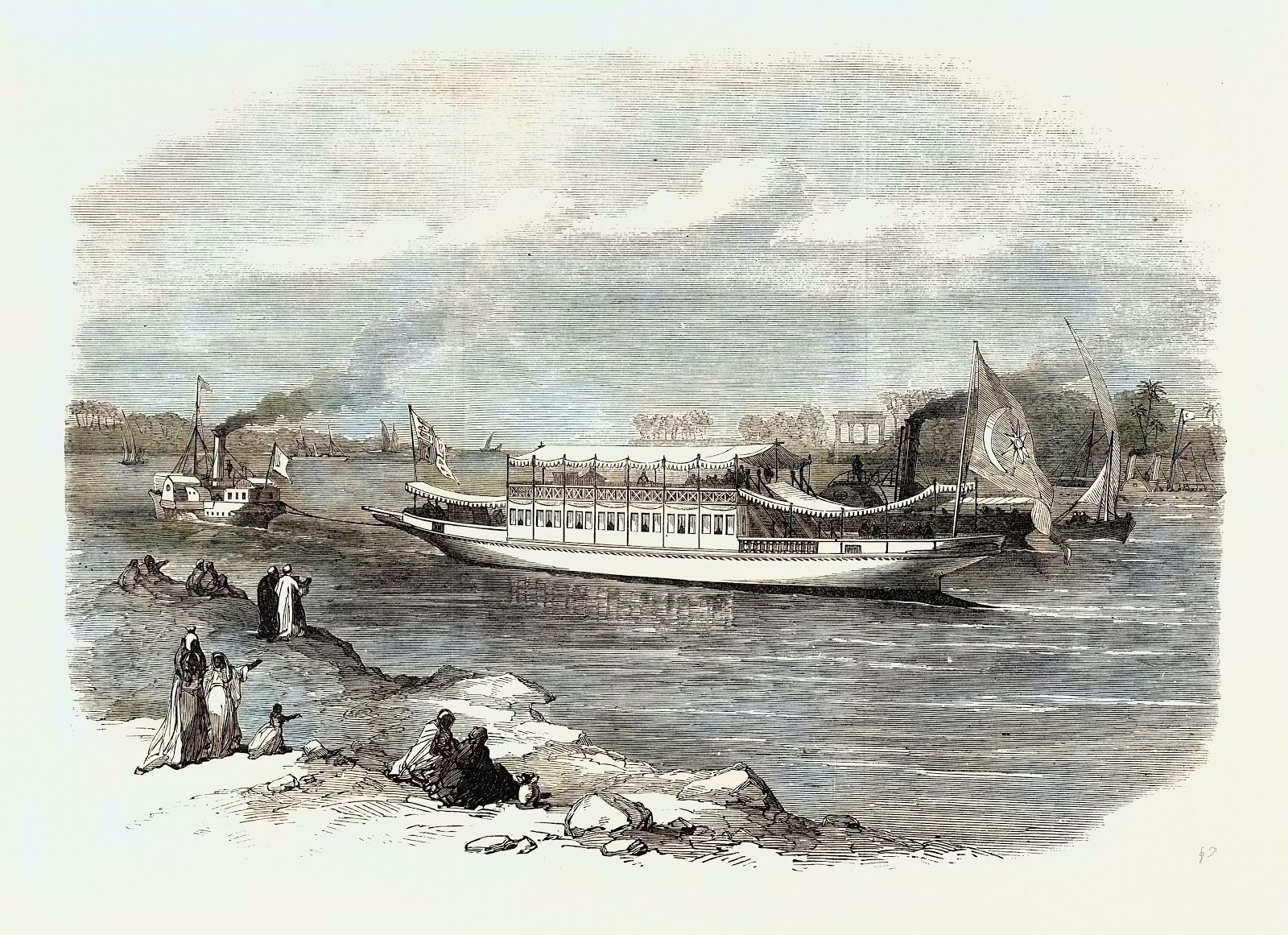

Houseboats, also known as dahabiehs (golden) or awamat (floater) in colloquial Arabic, have a curious, highly contested history. The first generation of houseboats was said to date back to ancient Egypt, belonging to ruling pharaohs and men of esteem. Centuries later in the 1800s, high-ranking Ottoman pashas used the boats as residences for entertainment and leisure. More recently, during the second world war, British forces lived within them.

Houseboats, it seems, are vessels etched into Egypt’s history.

To most Egyptians, these houseboats became famous as a result of Egyptian laureate Naguib Mahfouz’s work. His two novels, Sarsara Ala El Nil (Adrift on the Nile) in 1966 and Asr El Shouk (Palace of Desire) in 1957 – later turned into movies – beautifully depicted life on the Nile. Mahfouz is believed to have also lived on the houseboats, along with Egyptian icons including Abdel Halim Hafez, Egypt’s 1920 diva Mounira al-Mahdia, and singer Badia Masabni, also owned houseboats along Cairo’s banks.

“My father initially thought of buying our awama after being inspired by Naguib Mahfouz. He was fascinated by its presence in Abdel Halim’s movie Ayam w Layali [Days and Nights],” tells us Farah Helmy, 21, student at the American University in Cairo.

“[These boats] have been here for a hundred years,” adds houseboat owner and entrepreneur Jerome Geyer, 25, to Egyptian Streets. His own project, affectionately dubbed Houseboat 65, is one of the oldest on the Zamalek banks and plays host to various international visitors annually. “This home was bought by my family 30 years ago […] and before that it was owned by a Sudanese pasha. Most of the boats were owned by [established] pashas.”

Geyer goes on to delineate a past rich with heritage and royalty, citing names such as Princess Nazli Fazil—Egypt’s prized femminist princess and the late King Farouk’s wife—having owned their own floats in the area.

There were upwards of 200 houseboats on the Nile, prior to President Gamal Abdel Nasser, who cleared several to make way for water activities. From cultural paragons to symbolic movie shots, it comes as no surprise that many consider these structures part and parcel of the Cairene landscape.

Houseboat 65, Geyer describes, is something of a “palace” on the Nile: “Visitors feel like they’re living in a little space belonging to Egyptian heritage. Some cry when they’re leaving.”

Egypt’s history began on the Nile—and for Geyer, removing houseboats means negating that heritage.

“There were always rumors that they would [remove these boats], for the past 30 years maybe. [Most notably] during Sadat, when a minister wanted to remove them but got fired, because many influential people owned houseboats at the time. Now it’s happening again—and seems like they’ve got us for good this time.”

THE PRESENT: a race against time, and against decrees

Geyer, along with many others, received a notice earlier on in June 2022, describing how houseboats were “illegal” structures that needed removal per governmental dictat. The Ministry of Water and Irrigation posted pictures of impounded houseboats, noting that many others would be dealt with in the upcoming days as part of a program to reinvent the location.

The Egyptian government offered little to no information about its plans for houseboats, although commercial restaurants and floating cafes are set to remain in place. This falls in accordance with the government plans to modernize Cairo, building new roads, and bridges.

According to a source that spoke to Egyptian Streets, the houses won’t be demolished, but rather confiscated. The cost of relicensing the houseboats for commercial use amounts to nearly EGP900,000 (USD 47,855).

“[The Egyptian government] gave us the options of either removing our houseboat from its place or destroying it, but they’re keeping the commercial clubs, restaurants, and office houseboats. If the removal is defended by the ‘environmental well-being of the Nile,’ then it’s safe to say that commercial houseboats cause more pollution than our homes ever will,” tells Helmy to Egyptian Streets.

Despite this, officials have not yet specified what development is planned for the area that is now set to become bereft of its residents.

Their decision to demolish the houseboats is supported by a claim that the houseboats were built decades ago without the consent of the Egyptian government, and that the owners have failed to obtain the correct permits and licenses, which the residents contest.

Ayman Anwar, the head of the Central Administration for Nile Protection, was quick to support the claim “[The boats] are sitting there without any safety system. They do not have licenses from a single government authority.”

Owners have faced sharp and challenging increases in mooring fees over the past few years, but have continued to pay their taxes and fees in accordance with governmental regulations.

“We’ve always been legal,” Geyer insists. He describes a WhatsApp group where houseboat owners rallied together in an attempt to keep eviction from happening. Soliciting the best legal teams in the country, lobbying for assistance from high ranking officials, and petitioning to keep their homes intact: everything was done in an attempt to mitigate what seemed like an insurmountable reality.

Unfortunately for Geyer and his community, governmental powers seem decided.

“We got our notice only three days before its scheduled removal. It was devastating to know that we have to remove all of our belongings in a matter of 48 hours. We were robbed of our goodbyes to our home,” noted Helmy.

The Ministry of Water and Irrigation stated earlier this month that it will proceed with its plans to remove the houseboats, as they are “in clear violation of the law […] a clear message to those who transgress on the Nile,” Minister Mohamed Abdel Ati reported to BBC on 30 June. The government has also not offered compensation to those who are forced to flee their homes – for many, the only ones they have ever known, and own in a city of incredible living expenses.

“Even if you wanted to stop this legally, by court decision, you need 14 days,” Geyer explains. “The time frame they gave us didn’t allow [for that].”

Live during his call with Egyptian Streets, Geyer pauses—then scoffs. “There: they’re removing one now.”

According to Geyer, any structure more than 30 years old needs approval by the Egyptian Heritage Committee, but it seems that houseboats may not have been afforded that opportunity. Geyer, disappointed, adds: “There’s the law, and then there’s the practice of it.”

THE FUTURE: where to go?

There are [were] nearly 40 boats remaining from at least 200 over the decades near the Kit-Kat area, but its residents outcry as they find no solace for the tragedy happening.

“They’re destroying the past, they’re destroying the present, and they’re destroying the future, too,” said Neama Mohsen, 50, a theater instructor to the New York Times.

“We all talk about heritage,” Geyer states. “But there’s people that leave their jobs abroad—Egyptians, foreigners—that work to make their country great again and they get [screwed over].”

Geyer himself, as an Egyptian-French entrepreneur, left a steady job and a promising career in Switzerland in order to pursue his Egyptian inclinations here in Cairo. He describes Houseboat 65 as a labor of love: something he made from nothing, designed from nothing, and lives to see taken from him.

“Me, I had a good job in Switzerland. I was making good money. I was having fun. I quit everything to come back to my country, because it was always something I wanted to do. I renovated this thing which I thought was Egyptian heritage,” Geyer sighs. “And yalla, bye, bye: from one day to another. It doesn’t incentivise anyone to come back to the country.”

In a final note, he adds with heartbreaking cadence: “If I fail, and this [houseboat] goes away—one thing is for sure: I will definitely leave Egypt.”

Comments (5)

[…] The Cairene landscape recorded in the film is a distant cousin of the city we know today. In its opening moments, the camera pans across the western bank of the Nile, and rests upon the titular houseboat, home to our protagonist. The houseboats, paragons of Cairo’s heritage and once home to some of its most memorable film sets, now feel like relics of a different era, six months after their demolition. […]

[…] The Cairene landscape recorded in the film is a distant cousin of the city we know today. In its opening moments, the camera pans across the western bank of the Nile, and rests upon the titular houseboat, home to our protagonist. The houseboats, paragons of Cairo’s heritage and once home to some of its most memorable film sets, now feel like relics of a different era, six months after their demolition. […]