“My family and I stopped going to church because they would frequently get attacked, and the one we would normally go to [Saint Mary Church in Ard El Golf] was just recently threatened,” Kenzy Helmy* tells Egyptian Streets.

Helmy, a 20-year-old university student in the UK, opened up to Egyptian Streets about the public discrimination Christians in Egypt face on a regular basis. It is a feeling shared by many, that prejudicial actions are somehow protected in Egyptian society. Regardless of the laws implemented, Christians still feel the sectarian tensions from those around them, whether at work, schools, or in sports, and particularly during religious holidays – these tensions have become an unfortunate cultural regularity.

Discrimination, from past to present

Egypt is a country with a population of 104 million people, between 10 percent and 15 percent of which is made up of Christians – with the majority being Coptic Orthodox, and minorities of around one million Evangelical Christians and around 250,000 Catholics.

The Christian community has maintained a rich and deep-rooted 2,000-year history in Egypt since St. Mark the Evangelist arrived around 48 A.D. Despite Christians’ long and significant contributions to Egyptian culture and society, the community has been facing largely unprecedented levels of persecution and has been the target of violence and discrimination for decades.

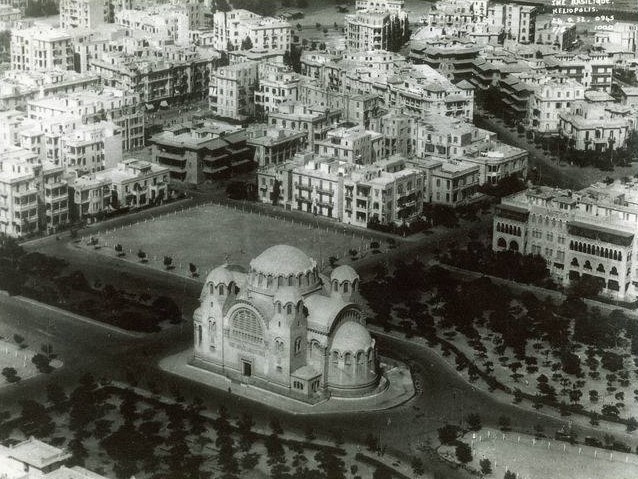

Christians in Egypt were not always subject to discrimination – in fact, Egypt’s religious discriminatory culture against Christians is relatively recent. Copts were prominently represented in the parliament and in Egyptian political life, particularly during the Liberal Age of the 1920s.

However, towards the beginning of the 1970s, violence, and sectarianism arose during the rule of President Anwar Al-Sadat, and were especially pronounced following the revolution of 2011.

During the period between 2011 and 2013, sectarian tensions grew particularly severe, as churches became target points for attacks with little intervention from security forces.

In 2020, the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) even recommended that Egypt be added to the State Department’s Special Watch List (SWL) – a list of countries whose governments tolerate and participate in severe religious freedom violations.

Unfortunately, this discrimination against Egypt’s Christians is also perpetrated in law and in practice.

Christians in Egypt suffer from multifarious types of discrimination including legal biases, biased implementation of laws, and social discriminatory acts.

A clear legal form of discrimination against Christians is, in cases of personal matters, if sharia law is implemented for a Muslim who wants to convert to Christianity; it is a serious dilemma as the state does not recognize conversions from Islam.

A highly publicized case of this particular issue occurred in 2007, when Mohamed Hegazy, a Muslim, wanted to convert to Christianity. The Cairo Administrative Court refused to rule on the case of Hegazy, who demanded his new religion be recognized by the Egyptian government. Hegazy spent two and a half years in unlawful detention before he issued a sudden public statement announcing his conversion back to Islam.

This prompted both human rights activists in Egypt and his attorney Karam Ghobrial to believe that Hegazy may have been forced to make the public act of conversion to get out of detention.

Church demolitions: a prevalent issue

While Egyptian law No. 80 of 2016 bans the closure of any church, security forces have repeatedly closed down and demolished churches in violation of this law. Article 235 of the Egyptian Constitution of 2014, states that “the House of Representatives shall issue a law to regulate constructing and renovating churches, in a manner that guarantees the freedom to practice religious rituals for Christians”. Yet, in 2017, there were several instances in which churches were closed – on the basis that they were illegally constructed.

While there are illegally built mosques in Egypt, they do not receive the same treatment. Perhaps the most well-known case of a demolished mosque was in 2019, when the state chose to demolish the mosque of Sufi Imam Abu al-Ikhlas al-Zarqani to complete the Mahmudiyah corridor project.

When the state was accused of demolishing mosques in 2020, the state authorities responded by saying: “We demolished 30 mosques, but we rebuilt them for the national interest and development — not because of what they had accused us of.”

Shukri al-Gundi, a member of the parliament, warned against these accusations saying that “Egypt would never remove mosques”.

The most recent case of a church demolition by security forces was in May of 2020, specifically a church in the Kom al-Farag village in Al-Beheira. The church was used for almost 15 years and needed expansion. Consequently, Muslims in the village protested the expansion, and contrary to law No. 80 of 2016, security forces did not wait for a court decision and proceeded with the demolition of the church.

Assaults and Social Discriminatory Acts Against Christians

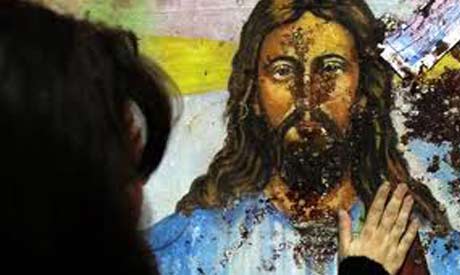

Apart from illegal, but government-sanctioned acts of discrimination, Christians in Egypt primarily endure discrimination on a day-to-day basis from other Egyptians. Assaults in Egypt are commonly in the form of church attacks.

In 2017, a gunman attacked a Coptic church and a Christian-owned shop that killed 11 people. There were also two other church bombings that killed 49 people, and finally, 29 people were killed by extremist attacks on their way to a monastery.

Besides church attacks and violent assaults, socially discriminatory acts are another dominant form of discrimination in Egypt, predominantly carried out in the form of hate speech and ill-treatment.

“Even if they aren’t direct attacks, I get a reminder of [the discrimination] whenever I see the national team’s lineup and not find a single Coptic player on there,” Mikhail Youssef* tells Egyptian Streets.

Hate speech and social discriminatory acts are usually exhibited during the month of holy Ramadan in Egypt.

“I mainly feel [the discrimination] during Ramadan. Walking with my sister in daylight, I hear every now and then, maseheyeen shaklhom (they look like Christians). We are not allowed to drink or eat, as well,” Youssef says.

While Christians are technically allowed to eat and drink, it is highly judged and frowned upon in society.

An unfortunate incident demonstrating this exact statement and exhibiting severe animosity towards Christians in Egyptian society occurred last April. During the holy month of Ramadan, the Egyptian daily newspaper Al-Masry Al-Youm published an article entitled: “What Is the Ruling on Selling Food to Infidels during the Daylight [Hours] of Ramadan?” The article essentially labeled any non-muslim an infidel and concluded that it is not permissible for a Muslim to sell food to “infidels” during Ramadan.

Following an uproar of disapproval and rage, a few hours later, the online newspaper deleted the article, suspended the journalist and issued an apology.

In another incident, in that same month of April, a branch of a famous koshary restaurant, Koshary El-Tahrir, was closed upon a complaint from a Christian woman, named Silvia Boutros, that staff refused to serve food to her and her child before iftar during the month of Ramadan.

Despite the newspaper’s public apology and the closure of the koshary branch, the published article and the restaurant’s refusal to serve the Christian family both demonstrate the commonly inflicted acts of discrimination against Christians in Egyptian society.

Many Christians in Egypt are afraid to speak up and take legal action against the personal discrimination cases they face, as they are frequently forced to give up their legal claims in order to avoid prosecution. Some do not feel safe to even discuss the topic.

“I had a friend who was rejected from piloting school and [the administration] literally told him it’s because “you’re Christian,” Lily Nasr*, a 20-year-old politics and business student in the UK states.

Many Christians are less willing to pursue legal cases against organizations or individuals that discriminate against them, as this can put them at risk of personal safety, public criticism or even persecution.

Education plays an important role in tackling discrimination and ensuring a tolerant and accepting society. It can either prevent or prompt religious and racial discrimination.

“Something else that bothered us was during Arabic classes, we would have to learn and memorize Quran verses. It didn’t bother us to see the Quran verses, but they would never include translations from the Bible,” Nasr tells Egyptian Streets.

Several Christians feel a sense of exclusion from history classes and educational curriculums taught in Egypt – which would undoubtedly add to their perceived significance in Egyptian society and culture.

“The only modern Coptic figure mentioned in educational syllabuses is Boutros Ghaly. There aren’t any Coptic figures or history taught about Christians in Egypt. And it isn’t just for representation, there truly is a lot!” Youssef tells Egyptian Streets.

Civil society silenced?

There have been several instances in which the Egyptian government targeted people who reported on religious persecution and human rights violations present in Egyptian society, including the blocking of online publications such as Mada Masr, as well as the persecution of journalists, and human and political rights activists. Mada Masr, which has been operating since 2013, was blocked in 2017 when the government raided the outlet’s editorial offices in Cairo.

Whilst, another prominent case of arrest was that of Ramy Kamel, a Coptic activist who was arrested on November 23 in 2019 on the charges of forming and funding a terrorist organization, misusing social media, and spreading false information.

Kamel was cooperating with the United Nations, documenting the Church burnings and attacks that erupted in October and November 2019 before he was arrested. The activist was invited to the 2019 Forum on Minority Issues in Geneva but was arrested one day before his scheduled travel to talk about the rights of Copts in Egypt.

An extended detention of 45 days was ruled without him or his lawyer being present to appeal. Kamel’s lawyers were also banned from reaching his prosecution. During the course of his detention, Ramy was banned from receiving any books or newspapers, and since March 2020, he is not allowed to communicate with any family or lawyers.

Governmental efforts to assuage?

Despite many social and systemic injustices towards Egypt’s Christians, the government has recently been making efforts to improve the social and political conditions in which they live.

Due to the political marginalization Christians have been suffering from for years, President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi has been taking necessary measures to ensure that Christians are not left out politically or socially. He is, for instance, the first Egyptian president to attend Christmas celebrations at the Coptic Orthodox Church in Cairo every year.

Apart from social and personal ties with the Coptic Orthodox pope – Pope Tawadros II of Alexandria, Sisi has ordered authorities to build a new church in each of the 14 new cities being constructed to cope with the country’s population growth, such as the Cathedral of Milad al-Masih (Nativity).

In addition, due to the president’s current efforts, more Christian candidates have been running for parliamentary elections in Egypt. In fact, in 2018, Pope Tawadros II stated that Coptic members in the House of Representatives have increased to 39 members, compared to only one or two before 2011. In 2020, around 108 Christian candidates ran within all four party lists.

While asking the interviewees what social changes they want to see in Egyptian society, Youssef says that “there should be administered organizational policies and serious ramifications for discriminatory actions. There should also be investigations conducted for someone who has been rejected for his religion or just performance.”

Helmy also suggests a change in the educational system and the curriculums provided.

“It would really bother us to be constantly asked to memorize Quranic verses and have our Bible completely disregarded,” she says. “It makes us feel like there’s a superiority between the two faiths – even in their significance in education. I would definitely like to see a change in regards to the curriculums.”

Coptic Christians interviewed by Egyptian Streets said that, apart from legal and state efforts, Egyptian citizens need to make way for a more united and tolerant society.

Youssef, Helmy, and many others believe that it is time to relieve the Egyptian community from all sectarian tensions and advocate building a society accepting of different faiths and beliefs.

“Christians should not fear going to church in their own country in case of a sudden bombing, or hide in basements in fear of attacks, like some of my friends have, or walk on the streets overhearing snide comments about their faith,” says Nasr.

Comments (0)