Egyptian gentrification politics are devoid of nuance, and more often than not, also devoid of empathy. Though gentrification in and of itself is a two-pronged beast—a discussion of poverty and heritage in the same, thinned breath—it is not a dialogue often held in Egypt. Instead, in a gut-scraping hunger for modernity, Egyptians have overlooked the destruction of homes in favor of world-class status symbols; ghettos and mud-brick slums are seen as open wounds rather than a haven for millions.

Barring cases where safety is the prime driver for demolition, it seems that gentrification has become commonplace to the point of dismissal.

For nearly six decades, across the globe, gentrification has been “confused with other urban notions such as upgrading and renewal,” regardless of the economic consequences it may have. In order to re-energize the narrative, one needs to take a keener look at gentrification “geographies,” the most prominent of which are third world communities: locations forced to modernize, with no one accounting for their local cultures, socioeconomic intersectionality, or social mobility.

Egypt is no exception—rather, it is the example. As the world remains in awe of Japanese architecture and Singaporean fintech, Egypt has scrambled to innovate its infrastructure and reconstruct its global image as one suited for the future. This chronic need to change, however, has come with a cost; from lands reclaimed by the government or rendered obsolete due to superhighways tearing through them, to the leveling of whole communities to build glass towers, the question begs itself: who is this all for?

And more importantly: who can afford it?

A Game of Government ‘Simon Says’

Gentrification is a nonlinear process, and in the Egyptian context, becomes hard to define. Generally speaking, it is seen as the process by which an impoverished area is developed into a richer one by means of pricing out the community historically residing there. The reason this becomes difficult to tailor to Egypt is largely due to the pervasive nature of informal settlements across the country; many families have taken to living on land that does not, by law, belong to them.

Over 38 percent of Egypt’s urban cluster is considered informal, and with a 27.9 percent poverty rate, the risk of displacement is significantly high for the majority of Egypt’s poorer areas.

While there is an argument to be made that most slums are the product of illegality, there is still a very real counterargument rooted in their visceral poverty; people constructed these makeshift homes out of a necessity, not an insidious urge to capitalize on what was not rightfully theirs. Even so, other populations who own the right to land, such as those of Al-Warraq, have still been forced to flee demolition.

Best placed by Egyptian urban designer and architect Ahmed Zaazaa, “forced evictions have become synonymous to new urban development, city upgrading, and the construction of financial and business centers in Egypt.” Although modernity is not, in its own right, a taboo topic—it becomes such when new developments are “executed upon the remains of displaced communities without their consent.”

The government has, in recent years, attempted to compensate displaced populations. However, some still argue that the alternatives have not been up to snuff, particularly for those with the right to stay. “Why do we destroy what makes us?” asks New York Times journalist Yasmine el-Rashidi when discussing Maspero’s gentrification.

Between meager financial compensation for landowners, to middle-of-nowhere alternative housing, to conniving political conspiracy meant to erase revolution—it seems that Egypt has not quite been able to rebrand gentrification as social resilience quite yet.

Instead, gentrification serves to create social polarization and loss of identity.

That said, it’s worth looking at the core drivers of gentrification in Egypt, not simply the people most-impacted by it. Scholars Muhammed Eldaidamony, Ahmed A. Shetawy, Yehya Serag, and Abeer Elshater divide the modes of Egyptian gentrification two-fold: historical tourism gentrification and contracting/real estate gentrification.

The former, historical tourism gentrification, is most often associated with clearing out old residential areas in favor of creating touristic hubs around key heritage locations in Egypt; the latter, and perhaps the more controversial of the two, is the leveling of impoverished residential areas for commercial purposes: selling property.

While most of Egypt’s postmodern real estate is situated in new, avant-garde cities—from Al-Alamein to the New Administrative Capital—there is still a very real threat embodied in “reclaiming” downtown locations and older locales.

For Zaazaa, another worry lingers: the uncertainty of what exactly will replace these “lost homes and national history.” Most ideations and blueprints seek to establish investment projects, and financial business centers; it becomes a socioeconomic conflict between the right people have to the location and the vibrant future promised in their displacement. Zaazaa adds that another conflict is at play, an urban one: to gentrify the heart of Egypt’s cities, or to move into the desert with new ones?

In 2008, Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouly, announced the “Cairo 2050” project: an initiative which aimed to “transform the heart of Cairo into a financial and business center.”

Between 2008 and 2011, many experts opposed this on the grounds that it would “replace Cairo’s identity and sacrifice social values.” While the project was halted for a short amount of time, it has resumed as of 2014 onward, and is most embodied in the Maspero triangle.

Maspero’s Bulaq neighborhood was demolished in 2018, and some still-standing buildings continue to fight for their right to remain in the area. The location has been sacrificed in favor of a sleeker skyline—one with high-rise residentials and business centers.

Bulaq residents were given three options in the wake of their “forced eviction”: a sum of money (EGP 60 thousand per family; USD 2,591), housing units in the Asmarat Project, or a housing unit after the area’s redevelopment. The last is a promising option, if not a beacon of hope for Maspero’s residents; still there is no clarity regarding the size, worth, and exact location of these units.

Around 12 percent of the residents opted for new apartments in the Asmarat Compound, while 80 percent chose financial compensation. Only eight percent insisted on returning to their home region post-development, given the uncertain nature. However, Zaazaa notes that since “strict stipulations on the treatment of redeveloped housing units are absent, it is expected that the new units will eventually be sold to reap the benefits of the new real estate value following their development;” in other words, far more value than what was used to compensate—with no clarity as to whether or not returning citizens will be asked to pay the difference out of pocket.

Between the sentimental, historic value held in Maspero—such as Egypt’s oldest watch shop meeting demolition—and the displacement of thousands of residents, many have begun to question if the gentrification of Egypt makes sense; if the general public cannot afford units in these sleek projects, if Egypt is already in mass debt, if displacement compensation causes strain on the financial treasury—then who is it for, really?

Bulaq is far from the most famous example, nor is it the most prominent. Other sites, such as the Arab al-Yasar neighborhood in old Cairo, are being primed for similar fates. Sections of Arab al-Yasar have already been leveled, this includes its historic cemeteries. The same compensation methods used for Maspero apply here, as well.

Though perhaps the most famous case is that of Gaziret Al-Warraq.

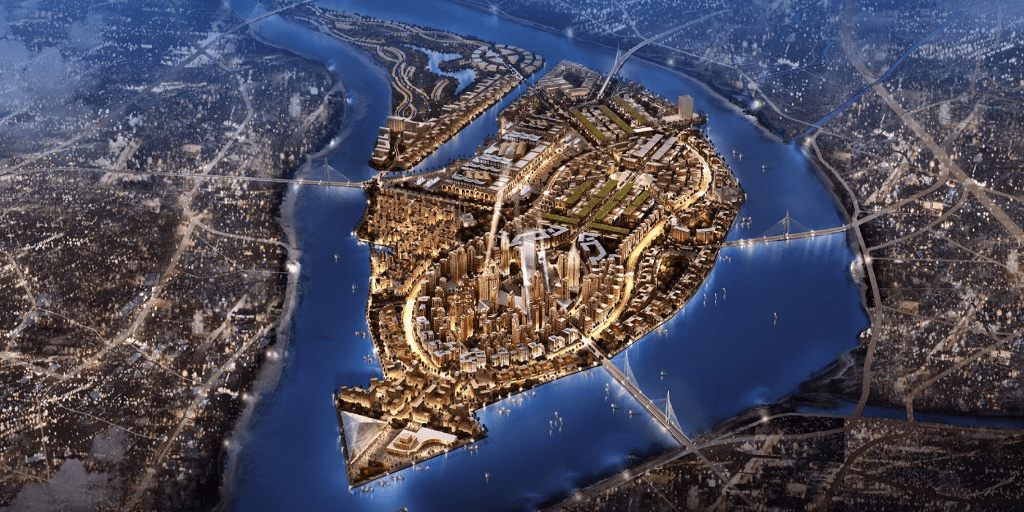

In audacious strides to modernize the location into the so-called ‘Horus City,’ a tongue-in-cheek allusion to the shape of the island, the government has been met with fierce protest. Police stormed the island to remove “encroachments” on state-owned land, and clashes rose between inhabitants of the informal settlements and the police. When security forces attempted to forcibly remove the buildings, the inhabitants of Al-Warraq rose in protes, firing bird shots and throwing stones, according to a statement released by the Ministry of Interior.

Though cloaked as “slum improvement,” the events of Al-Warraq leave many insecure about their housing.

The urge to modernize is not inherently bad, but one must take into account the sheer gravity of independent cases, and the socioeconomic divisions of Egypt as a country. Egypt struggles with finding its own brand of modernity, and given that most of its population reside in informal slums, some forms of modernity come at a grave cost.

While, over the years, leaders such as Gamal Abdel Nasser and current President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi have tried to develop sufficient government housing, those at risk are not only illegal, informal settlements but people with the right to land. That said, the legal and ethical gray area is impossible to divorce from Egyptian forms of gentrification.

The opinions and ideas expressed in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of Egyptian Streets’ editorial team. To submit an opinion article, please email [email protected].

Comments (0)