Midway through a 400-kilometer journey from Lusaka, the calm capital of Zambia, and Livingstone, a well-known city replete with natural protectorate parks along the border of Zambia and Zimbabwe, I found myself struck by a miniature existential crisis.

The day had been spent wonderfully, with me sampling shoka nyama (grilled street meat) and bananas right from the streets, and pestering two officers from the Zambia Tourism Agency, Agatha and Martha, with a plethora of questions akin to a 5-year-old.

The weather in Zambia was perfect, a crisp 20 degrees that strongly contrasted with Egypt’s summer heat, and the company I was keeping was jovial.

How is it then, that I had been struck with one of my bouts, while I was 6,764.6 km kilometers away from home?

Even in the southern African country, I had found myself seeing my friends’ Instagram stories. Some were getting married, others were having their first child, and some were absolutely killing it at their jobs or have had the most wonderful, picture-perfect summer adventures.

The endless, joy-killing scrolling had left a bitter taste in my mouth and left me wondering, as many of my generation do, if I was doing enough of what I ought to be doing to survive in a fast-paced, visually-obsessed world where status and monetary gains propel individuals forward.

Yet, here I was, on a breathtaking trip to one of Africa’s pearls, with the utmost privilege of writing about it. I felt my bitterness laced with shame and regret that I had had a momentary trifle of vulnerability. And, while I studied the endless white butterflies as they zigzagged through the highways, my mind immediately traveled to the Choma museum we had earlier visited that day.

The Choma Museum: Celebrating the Tonga

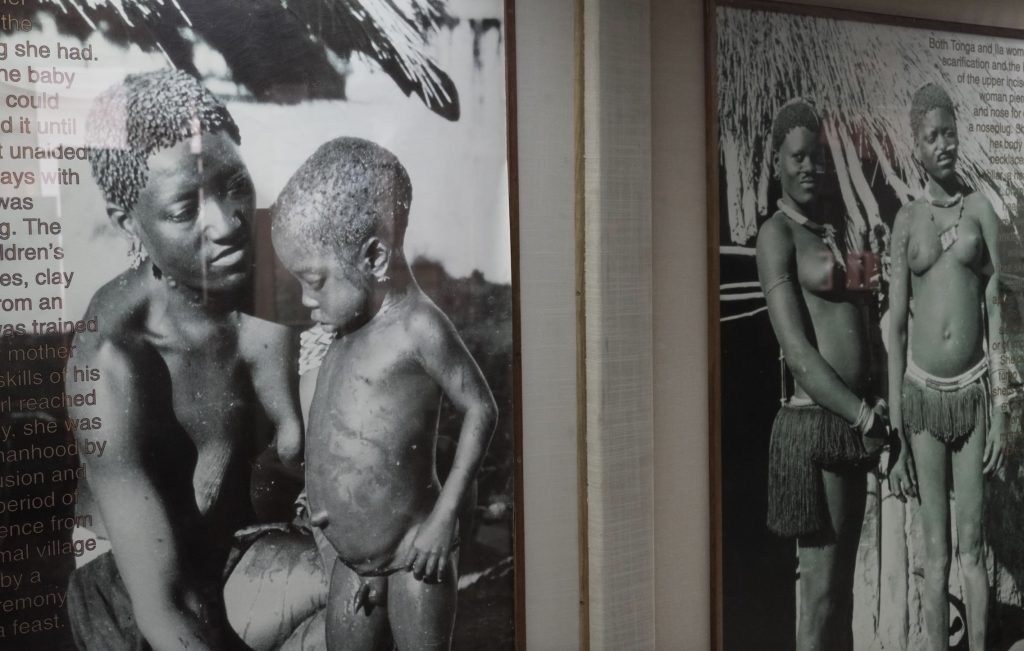

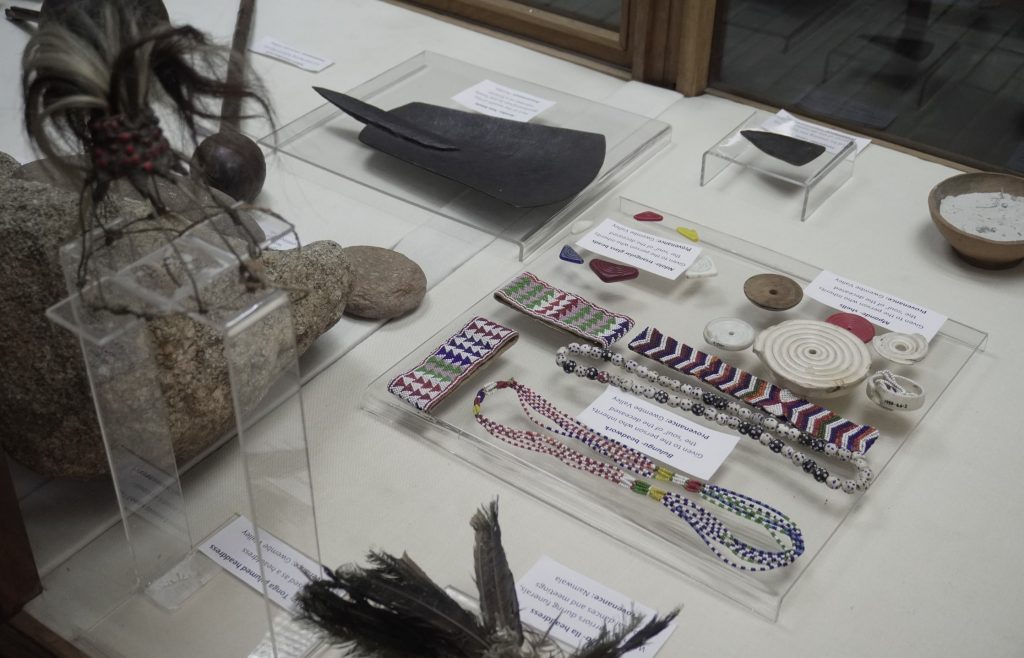

The Choma museum, one dedicated to ethnography, art, and crafts, in the quaint village of Choma (the Choma refers to a traditional drum) displayed the life and death cycle that every member of the Tonga, one of Zambia’s 72 tribes, goes through. In elaborate display cases of black wood and translucent glass: their beads, the women’s smoking gourds, human fat used for witchcraft, and many more everyday tools are left on display.

The Tonga are not unique to Zambia, indeed, the Bantu-speaking people live in both Zambia and Zimbabwe and have been the focus of much anthropological study, as they have maintained their knowledge system and both intangible and tangible heritage across generations.

The Tonga are known to have survived displacement due to the building of the Kariba Dam, significant changes to their landscape, and incorrigible Christian conversion. Yet, their ancestral spiritual values as well as veneration of the environment with which they harmoniously live with and draw sustainable natural resources from, lives on.

The museum and arts center is a modest establishment: while not many stop there, it should be on everyone’s travel list not for the modernity of its content, but because it is truly one of the few places in Zambia that gives visitors a peek into what it means to live culturally authentically, and differently, from the masses.

I couldn’t help but marvel at the collection, with many thoughts pirouetting in the crevices of my brain: did the Tonga people suffer from the same existential calamities we all did? Did they also feel regret and greed at watching others live their lives in specific ways? The answer must surely be yes.

How was it then, that they managed to survive and maintain their cultural distinctness over the years?

Zambia had previously been colonized by Britain, obtaining its independence in 1964, 42 years after Egypt. The country was not immune to internet influences and trends, and while many women still wore the chitenge (richly decorated patterned fabric) as skirts, there was a slow veering to fast fashion. International artists liked to make their way to Lusaka for large musical concerts and festivals; and restaurant chains from South Africa – such as Hungry Lion or Debonairs Pizza – slowly etched themselves into the country’s landscape.

It was upon talking to many Zambians during my trip that I understood that there was a deep reverence for roots that trumped the pervasive and popular influences slowly metastasizing from the West.

Zambians take great pride in their tribal roots, with Tonga men still offering their brides cattle as dowry. Similarly, cultural ceremonies and dances are practiced until today, safeguarding the country’s intangible heritage: Chiyada, Chingande, Vimbuza, and Chimbanda interlaced story-telling, rich fictional characters, and traditional dance.

Zambia’s unique tapestry of culture is mostly preserved through Traditional Cultural Expressions (TCEs) or ‘expressions of folklore’.

Similarly to Egypt’s folkloric tradition of belly-dance, tanoura or dance troupe, and extensive tradition of pottery making, many of Zambia’s tribes have prevailed due to a careful and routine re-production of cultural expressions. For instance, the Tonga are particularly well-known for their artistic creations, which include basketry, pottery, sculptures, and wood carvings. Tonga women in particular create intricately patterned baskets, from reed, palm trees, and bamboo, which are still made and sold at the Choma museum to this day.

While I did not have the pleasure of interviewing any of the Tonga tribe members, a glimmering realization came to mind: among the country’s almost 20 million inhabitants and this world’s 7.8 billion, there was a tribe that stood apart sheerly by being.

The women lived their lives according to the traditions of the tribe, pummeling corn into meal and inserting piercings into their noses, while the men focused on herding cattle and conducting witchcraft for power and virility… Here was a living, breathing tribe still residing in Africa that lived so differently from the westernization and globalization that had even pervaded the most remote areas of Egypt, and it continued to live on despite the pressure of the contemporary world.

Game Rangers International: the Wildlife Discovery Center

Zambia has taught me a lot about tenacity on top of authenticity: from the way its tribes live on, to the careful preservation and conservation of its wildlife, I am once more reminded of the importance of genuinely embracing uniqueness and cultivating a sense of resilience.

One stop that was essential to learning these lessons was the GRI Wildlife Discovery Center, a protected reserve not too far from Lusaka (about one hour’s drive away).

The Center is a safe haven for elephants. Not only does the center provide conservation education to up to 5,000 children each year, it has also recently – as of 2022 – opened the famed elephant nursery, which relocated entirely from Lilayi (south of Lusaka).

The baby elephants, some a few months old – and my favorite being the playful baby Matthia who liked to roll around in mud – were saved from poaching attempts by the country’s numerous wildlife rangers. Many of these elephants had lost their mothers in the poachers’ quests to obtain ivory, a most coveted white material stemming from elephant tusks which had been often-times used in the fashioning of jewelry and household trinkets.

The Wildlife Discovery Center was not just the home of the elephants, but it also provided a glimpse into community and governmental efforts to ensure that the country’s wildlife was protected for current and future generations.

One of the rangers’ pillars, adequately highlighted at the center, was that it took a village to safeguard the country’s natural heritage. Rangers, I was told by the center’s marketing officer, worked hand-in-hand with village communities.

When a baby elephant was left to ensure its own survival after the death of its mother, and had been seen trudging along the edges of their village, it was the village members that alerted the rangers that the animal was in need of rescue, rather than side with international poachers that could be spotted sometimes helicoptering over Zambia’s plethora of natural parks.

On cultural liminality

One study, from 2000, revealed that there were distinct ways a Tonga man made it clear he wanted to marry. One of these clever, yet possibly not too indirect, ways was to sing love songs and play the kalumbu (a single metal-stringed bow instrument) or kankobela (a thumb-piano) through the night.

Part of me wants to believe that in one of the Tonga’s many matrilineal or patrilineal clans, a smitten young man still brings his affections to his parents’ attention the same way. It might be hard to imagine, in this world of furtive WhatsApp texts and emojis, that such romantic innocence still lives on. Yet, Zambia’s rich culturalism expands one’s mind to the many ways human expression and palette of emotions could be expressed.

In these realizations, I found some solace in my crisis. I had acquired an understanding that the human journey was deeply personal and intricate. There was no need to pounce on joining the stream of the masses in terms of how to live, how to express oneself and experience life’s milestones. Rather, it made more sense to embrace uniqueness, acceptance, and diversity, as the Zambians do.

In a land where no McDonald’s could be spotted, and groups still gather in the village squares to gossip in the late afternoon – as the sun sets behind them – Zambia conjures the image of ancestral land, painted with vibrant practices still alive today.

Perhaps, in the not-too-far future, matters will evolve and younger generations will opt to attune themselves to the new ways of globalization, as they have begun to do in the bigger cities, but for now, it remains one of the few places where the soul of its tribes resiliently zigzags across the channels of cultural diversity.

This article is part of the Zambia Series, a series of articles and features aimed at highlighting unique aspects of Zambia’s heritage and tourism. The content is a byproduct of a familiarization trip undertaken under the auspices of the Zambia Tourism Agency.

Comments (0)