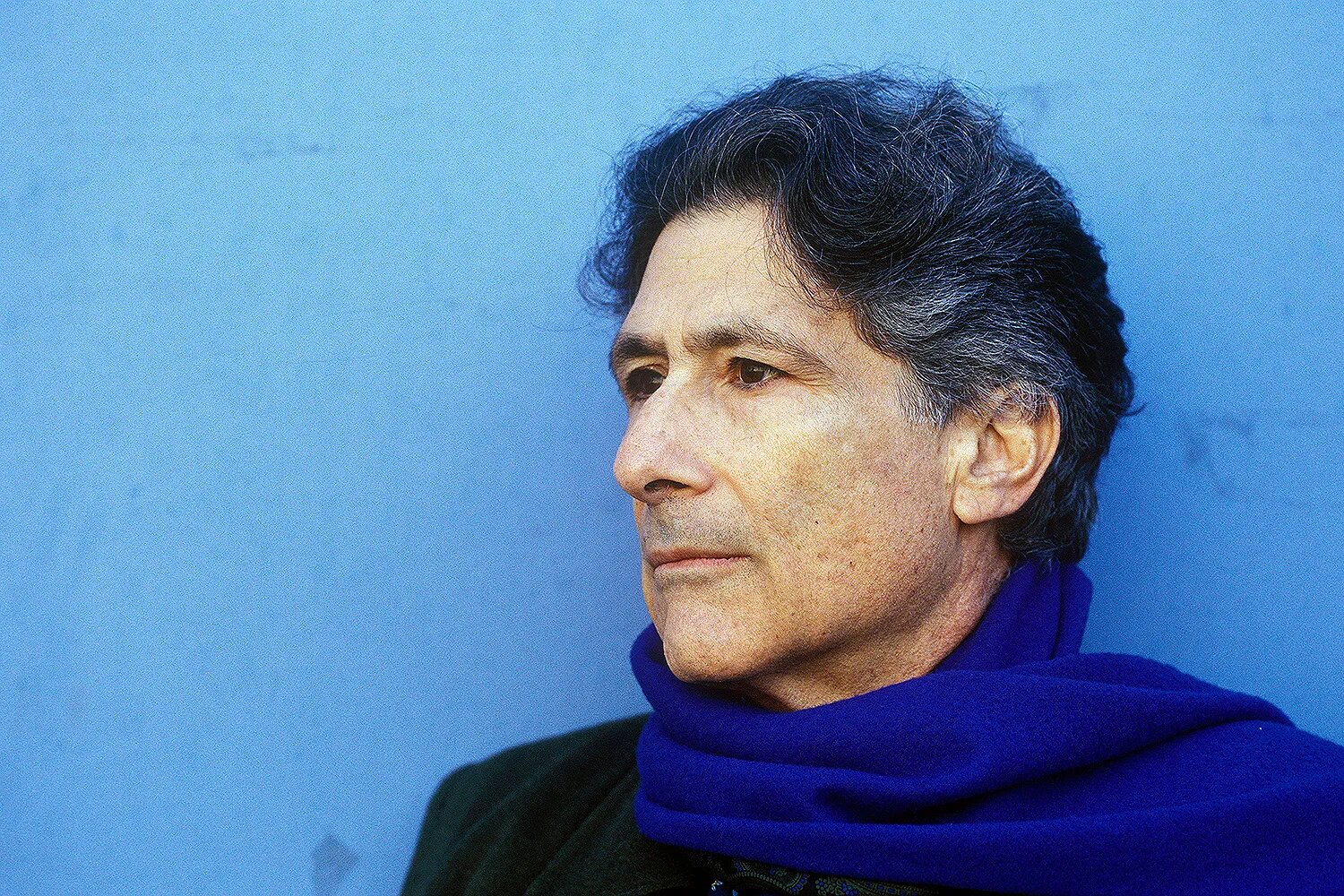

When Israeli officials routinely asked prominent Palestinian-American scholar Edward Said when exactly he left Israel after birth, since his US passport showed that he was born in Jerusalem, he responded by correcting them: he left Palestine, not Israel, in 1947.

The word “Palestine” was still a stranger on the tongue in Said’s time, but to him it was a lifeline — the only tangible tether to memories of his displaced and stateless kin, scattered across the globe since 1948. His legacy as an architect of the meaning behind words such as displacement and the “Other” rests on his understanding of the power that a single word can wield.

Twenty years after his passing, Edward Said’s words echo louder than ever, reminding us of the weight of our words and language. In the midst of linguistic and physical displacement, he laid the intellectual foundation for the recognition of marginalized peoples on a global scale, cementing their historical right to representation and visibility.

Said, born in Jerusalem, Palestine, was displaced by the Nakba (1948) — the Arabic word that refers to the mass displacement and dispossession of Palestinians. He received his PhD in English literature from Harvard University in 1964, and later taught at Columbia University for the rest of his career. While his work is best known for revolutionizing our understanding of the East-West relationship, he was also a vocal critic of the persistent silencing of Palestinian voices in mainstream media and academia.

Identity Crisis: a paradox of power

Edward Said’s profound insight that language, itself, can make marginalized people feel more visible still rings today for many that struggle to verbalize the horrors they have gone through. “Everyone lives life in a given language,” he observed. Everyone encounters, absorbs, and remembers memories in that particular language.

The experiences we hold and carry within us guide our tongue, and the way we experience the world is also in parallel to the way we speak about it.

To liberate his identity, Edward Said first had to translate his own experience of displacement into phrases, expressions, and terms that could resonate with audiences who had never seen, witnessed, or observed what he had gone through.

In his acclaimed essay, ‘Reflections on Exile’ (2000), he elaborated more clearly the struggles of the Palestinian experience through dissecting the meaning behind the word ‘exile’. Palestinians were not just immigrants, but were permanently exiled. In his essay, Edward Said articulated exile as an inescapable rift between the self and its native place, a sadness that can never be fully overcome. He described it as a state of insecurity, solitude, rootlessness, and displacement, in which one is “always out of place.”

For Said, and for Palestinians, exile is not a choice, but rather a condition into which one is born or thrust. Said’s concept of exile is inextricably linked to the expression ‘between worlds’. He wrote that while most people are rooted in a single culture, setting, and home, exiles are aware of at least two, which gives rise to a “contrapuntal” consciousness, much like the simultaneous harmonies and rhythms of a musical composition.

Caught between two homelands, two tongues, two cultures, and two ways of seeing the world, Said’s work is an attempt to discover the contours of his Palestinian identity only to find it shifting like the sands beneath his feet. The simple feeling of being at home, a birthright for most, was for him elusive, if not entirely beyond grasp.

Edward Said also recognized that his identity crisis was a paradox of power: by speaking of his experiences as a stateless individual, and by selectively and purposefully using the words “exile” and “displacement,” he made his identity more visible, forcing the world to see him and his people.

Reflecting on his childhood years, he incisively observed: “Though indoctrinated to believe and think like an English schoolboy, I was also conditioned to internalize my status as an alien, a non-European Other, educated by my betters to know my place and not aspire to Britishness. The line separating Us from Them was linguistic, cultural, racial, and ethnic.”

Though his Palestinian identity goes unacknowledged and endlessly challenged, the paradox is that it is that very act of the erasure of his identity that lends more visibility to it. The more his identity became questioned, the more he spoke about it.

In the face of the harrowing war on Gaza, and as Palestinians face a rising tide of erasure and silencing, Edward Said’s work reminds us that there is more than one way to be visible: to linguistically anchor our lived experiences.

Comments (2)

[…] When Israeli officials routinely asked prominent Palestinian-American scholar Edward Said when exactly he left Israel after birth, since his US passport showed that he was born in Jerusalem, he responded by correcting them: he left Palestine, not Israel, in 1947. The word “Palestine” was still a stranger on the tongue in Said’s time…Read More […]

[…] post “I Left Palestine, Not Israel”: On Edward Said and the Power of Words first appeared on Egyptian […]