It is known that sexual harassment has long been a problematic topic for Egyptian women to talk about. There has always been social and domestic pressure in terms of whether or not women should speak up about these harassment incidents and report them. Although government initiatives have recently highlighted punitive measures for harassers and the significance of reporting, many are still reluctant to do so despite this phenomenon being prevalent.

Following the #Metoo movement that went viral in 2017 in which women across the world started to speak about their sexual harassment stories as well as speak up against it, many men also started to reveal their experiences as well. Men have taken to social media, particularly, to talk about sexual harassment more openly, debunking the myth that this act of aggression only happen to women.

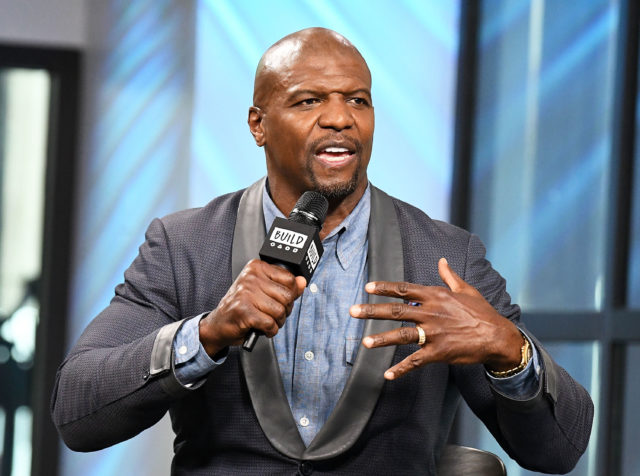

One of the most notable male advocates is American actor Terry Crews, who narrated how he was groped by a Hollywood agent, Adam Venit.

In an interview with New York radio station Hot 97, Crews spoke about how speaking up about the matter might weaken his well-known masculine and muscular image as well as make him the laugh of the industry, but he persisted to raise awareness on how men do get harassed as well.

However, what about the men of Egypt? Although the thought of this will perhaps raise eyebrows, it is an important phenomenon to acknowledge.

Defining harassment and transgressions

Even though Egyptian society has systematically punished women for speaking up against harassment as well as inflicting victim blaming, a lot of similar tactics that have been used to shun women have also been used on men in belittling their experiences.

There’s a significant distinction between sexually harassment and sexual assault. According to the Oxford Dictionary, the former is defined as “behaviour characterized by the making of unwelcome and inappropriate sexual remarks or physical advances in a workplace or other professional or social situation”, while the latter is defined as “The action or an act of forcing an un-consenting person to engage in sexual activity”.

There are various forms of harassment recognized by law in Egypt.

The second form of verbal sexual harassment is known as “Taharoush” which is when the predator uses provocative language or action towards the victim without physical contact. It can be a look, a word or a commonly understood inappropriate sign.

The harasser can then be imprisoned for a year or up to three years or pay a fine worth at least EGP 10,000 up to EGP 20,000.

In the case of physical harassment or assault, it is considered as “Hadf ‘Ard” under the Egyptian constitution Article 268. This is basically any form of unwanted physical contact between the predator and the victim. It is important to mention that forced sexual intercourse using foreign object or fingers is also considered “Hadf ‘Ard” rather than rape.

Legally, the harasser could receive a prison sentence between three to 15 years which could escalate to life imprisonment depending on the severity of the action.

Stigma laden with shame

Arab societies tend to emphasize men as hyper masculine, belittling emotion and sensitivity which are both seen as feminine traits.

‘’The very first time it happened, I was 16. I was waiting for the rehab bus and a person approached me; he asked me if I watched porn or if I masturbated. He was very freaky, and I was very young, so I didn’t know what to answer,’’ narrates 24-year-old Hussein Ali*.

‘’When I went home that night, I told my mother; I didn’t feel like there was a barrier that I shouldn’t tell my mom. I was shaken and breaking down; I needed to tell her mainly for support and didn’t feel ashamed. I remember that she told me, in a very traditional Egyptian motherly way, that I was wearing very tight jeans and that I ought to lose weight,’’ adds Ali.

Ali further explains that he did and does not feel like he would report the incident. Although he is open about speaking against the phenomenon and sharing his stories, he believes that most people are unaware and tend to only focus on the act being committed by one man against another man in allusion to homosexuality than focusing on the harassment.

Ali also recounts times where he was grabbed in the metro, and even, to his dismay, stalked by other men.

Tariq Abdel Nasser, a lawyer that specializes in sexual harassment cases, highlights that the general consensus in the Egyptian society is men are often “pleased when a woman comes on to them.” This reinforces the stigma surrounding male harassment making it more difficult for men to talk about their experiences.

In a research article written by Heather Hlavka titled ‘Speaking of Stigma and the Silence Shame’, she says “sexual coercion and assault embodied threat to boys’ (hetero)gendered selves, as they described feelings of shame and embarrassment, disempowerment, and emasculation. These masks of masculinity create barriers to disclosure and help to explain the serious underreporting of male sexual victimization.”

In terms of the legality of the assault, the law has two penal codes that can help women and children victims, however, none seems to exist for men.

According to Nasser, theoretically speaking, the law isn’t necessarily gender-based when it comes to such cases, it pertains to both men and women. However, most cases that include sexual harassment or assault against men are for survivors that haven’t reached puberty yet.

While there are no reports or data on the topic, a report published in 2015 by The National Sexual Violence Resource Center (NSVRC), an American non-profit, has found that nine percent of men have been raped or sexually assaulted .

“I had a couple of friends over and a stranger came by. He’s supposed to be well-known person in the neighborhood; he’s old and married. He was sitting outside and the small garden talking and chatting with the friends. He asks where the restroom is and I take him to the bathroom inside the house. He comes to me and says that he wants to tell me something; he hugs me and starts to get really quirky. He was touching me inappropriately on my private areas”, 21-year-old Ahmed Ibrahim* told his story about how someone sexually assaulted him in his own home.

“He leans in and tries to kiss me. I ordered him to leave my house afterwards. He was shocked. Later on that night , I received a text from that person saying that I should’ve taken it more normally, should’ve let it happen. I was shocked.”

“I wasn’t in contact with anyone for a short period of time. I had major trust issues because of it. I spoke to my psychiatrist and my friend that invited him. I also had security issues when it came to strangers and my guard was all the way up”.

It is worth noting that upon writing this article, several sources were confused or being sarcastic about the topic male sexual harassment.

It would not be wrong to presume that men being sexually harassed or assaulted is not as common as it is for women, but its mere existence is overshadowed by the incapacity for victims to make the crime visible or heard of.

Society shunning victims for speaking up about these experiences further pushes the notion that these topics will forever be a taboo and that survivors will in fact not survive any longer, hence many of them turn to drug addiction and even suicide to end their suffering.

It is sometimes even expressed by male foreigners in Egypt who complain of harassment especially by Egyptian school girls.

However, in the last years, various initiatives have sprung up in Egypt to make this problem more visible.

One of these is SAFE, one of the few Egyptian non-governmental organizations aiming to combat child sexual abuse by rendering children, both boys and girls, aware of transgressions occurring at the hands of predators.

Another important, albeit indirect, method of spreading awareness on the issue is often times through the Busy Story. The latter being a ‘’performing arts project that documents and gives voice to censored untold stories about gender in different communities in Egypt.’’

Stories shared by both women and men concerning harassment, honor killing, rape, forced marriages as well as others are shared in public performances that ultimately aim to spread awareness.

*Names have been changed to protect the anonymity of sources.

Additional reporting was made by the Egyptian Streets staff.

Comments (3)

[…] the stigma associated with sexual violence, thousands of Egyptian women and girls are joining a rising call […]

[…] Source link […]