There’s a long and winding staircase, its rails sanded mahogany and its steps slanted; at its landing is the crumpled body of a little girl.

Dorothy Eady was pronounced dead in her family’s London home at only three. She had been a lively child, bright-eyed and curious, born in January of 1904. Her fascination with life came to a brief, terrifying standstill that winter morning after suffering a fall down the stairwell. Only minutes after having been called in, the family doctor delivered the news to her parents: little Dorothy – a mess of birdbone limbs and youth – was dead.

Only she wasn’t, and an hour after her initial collapse, Eady was found upright and restless in her bed. Thankful and unquestioning, her parents dismissed the doctor; little did they know that the homemade miracle they’d witnessed was the onset of a new moon for reincarnation dialogues.

Eady would go on to become a modern colossus of controversy, notoriety, and interest – and she would do so by claiming herself a reborn ancient Egyptian priestess, Bentreshyt.

Galleries of Another World

On a trip to the British museum in 1908, Eady’s parents would notice a tangible shift in her behavior. Unlike the jaded and unimpressed children her age, Eady was noted to have a lit wick behind her eyes that burnt brighter when she set foot into the gallery of ancient Egyptian artifacts.

Without hesitation, she pressed hands up to glass displays and knelt to kiss the feet of statues. It was a bizarre sight for onlookers, more so when Eady took a seat by a preserved mummy, and insisted that she be left there. When her mother made to pick her up, Eady is quoted as having reiterated: “Leave me here, these are my people!”

According to a BBC TV documentary, after her trip, Eady’s dreams took her to saturated gardens and columns of limestone; she would rise in the middle of the night, tearful and heartbroken, insisting to her concerned parents that her home was elsewhere, and that they needed to take her there. Despite attempts to reassure her, their words fell on deaf ears, and Eady’s incessant dreams and breakdowns became a staple of their nights.

A few months later, Eady would come across glossy polaroids of Egypt: winding Nile banks and ibises, farmland and black mud, hieroglyphs that she expressed recognizing but not understanding. Buried within this stack was a picture of Abydos, in it, the Temple of Seti I.

“This is my home!” Eady ran to her father, desperate, “This is where I used to live!”

A Spirit Drifting to Cairo

Eady’s dreams had begun to make sense, and what were once dismissed as the ramblings of a child were only further solidified when Eady’s obsession with Egypt would continue on through her teenhood and well into her married years. She would cite a “spiritual connection” to ancient Egypt, intimate and unshakable. Over the years, she would dedicate her youth and early adulthood to the study of Egyptology and reincarnation, according to the fourth edition Journal of Egyptian Archaeology.

Although she was interested in the latter, Eady never found herself subscribing to the logic and present reincarnation narratives. She could not describe the process, but only that her dreams had been of Egypt as it had been.

“I had only one aim in life,” Eady is noted saying, “and that was to go to Abydos, to live in Abydos, and to be buried in Abydos.”

Cairo welcomed Eady in 1933, when she married an Egyptian man called Abdel Maguid and moved to Egypt. After giving birth to their first child, Eady insisted on naming them after Egypt’s 19th Dynasty ruler, Seti. As per Egyptian custom, Eady renounced her birth name and began going by Om Seti – mother of Seti.

Consciousness of A Priestess

Eady and Abdel Maguid’s marriage was a strained one, deteriorating rapidly as Eady became more and more infatuated with her studies. Unresponsive and trance-like, she would rise in the dead of night to write pages upon pages of hieroglyphics, sharp lines and quick thoughts scribbled down near-unintelligible to all else but Om Seti.

Abdel Maguid’s father would recall an anecdote, where he witnessed “a pharaoh” kneel at the foot of Eady’s bed, and soon after, Abdel Maguid himself would put an end to the marriage entirely. This allowed Eady to dedicate body and mind to her research: a 70-page manuscript she had written subconsciously. She would later refer to this as her spirit guide (Hor-Ra), as it delineated most of her past life, memories, and experiences.

According to her Hor-Ra, Om Seti had been an ancient Egyptian priestess named Bentreshyt. She lived in the Temple of Abydos during the reign of Pharaoh Seti I, and at the age of only 14, became his illicit paramour. Om Seti recalled having taken an oath of chastity and loyalism that was disrupted when the king took a liking to her. After falling pregnant, her need to protect Seti’s honour saw her taking her own life before birthing the child.

Om Seti would describe visits of how the pharaoh would come to her in her sleep, promising her of an afterlife with him in Amentet, the ancient Egyptian afterlife.

The Temple Garden

Her stories, unsurprisingly, were met with wide disdain and skepticism. Om Seti would soon plant the ultimate doubt inside her detractors when she led Egyptian archaeologists to the central garden within the Temple of Seti I. It was the place she had dreamt of for decades, and although it’d been eroded and destroyed over time, Om Seti had pointed to the exact plot of land. After meticulous excavation, it was undeniable: there was once a garden, with her exact recollections of tree types and arrangement, in the unexplored spot.

She described images never disclosed to the public with startling accuracy, in pitch black darkness, and told other obscure yet accurate tales. Om Seti was accurate in her description of water canals and the height of columns that no longer stood, translating some of the more arcane hieroglyphs with relative ease.

Slowly, the locals had begun to fear her, for lack of a concrete psychological or spiritual explanation.

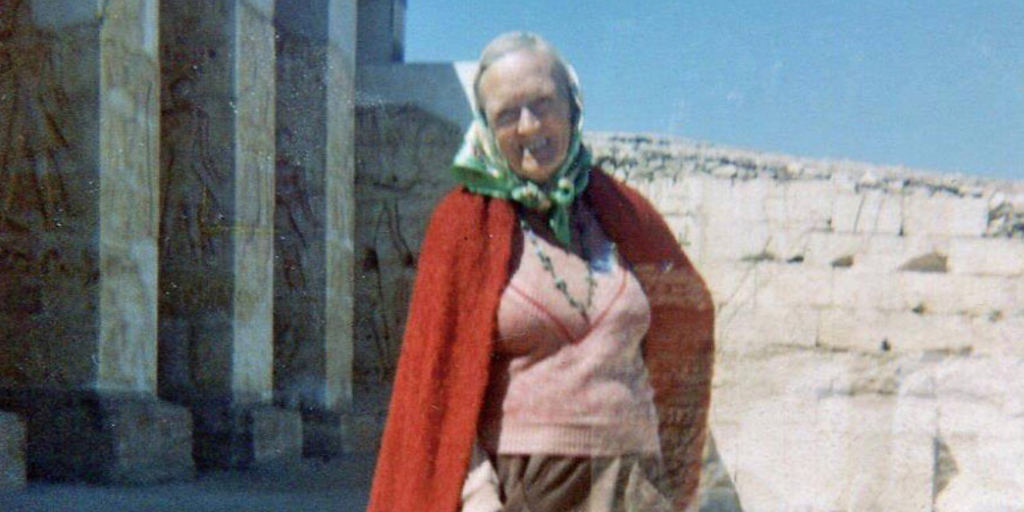

In 1956, she became the first woman to work in the Antiquities Department at Abydos, and took residence in the temple itself. She would also lead archaeologists to a tunnel, north of the temple, which had gone unnoticed for decades. According to Om Seti, her advice was a product of her memories of having lived there (per: Dictionary of Women Worldwide, 2007).

She would live the rest of her days at the Temple of Abydos, talking of an undiscovered library that sits under it – brimming with unseen religious texts and historical documents. Although no excavation has validated or dismissed her claims, Om Seti would pass on 21 April, 1981.

During her life and well after her death, Om Seti remains a point of contention among Egyptologists. Although strange and outlandish, her claims have confounded archeologists with direct truths and tangible findings. Some would describe Dorothy Eady as well-educated and well-spoken, far from the eccentric witch others have insisted she must have been. Nothing is certain, however, save the legacy of curiosity, confusion, and pure romanticism Dorothy Eady’s fateful fall brought into the world.

Comments (2)

[…] What about the story of the British woman, Dorothy Eady? She took a downstairs tumble at age 3, and was initially pronounced dead. Shortly thereafter, she awoke and believed she was a priestess named Omm Sety from Ancient Egypt. How could she have had such eerily accurate knowledge of hieroglyphics and long buried temples if she was not reincarnated? https://egyptianstreets.com/2021/09/13/from-london-to-ancient-egypt-the-reincarnation-of-dorothy-ead… […]

[…] المصدر by [author_name] كما تَجْدَرُ الأشارة بأن الموضوع الأصلي قد […]