Egyptians are more open to women in politics, but why are we seeing little evidence of that?

A survey published by Baseera, The Egyptian Centre For Public Opinion Research, stated that 83% of respondents agreed that women should have equal rights as men when it comes to political participation and equal opportunities as men when it comes to parliamentary elections.

This is a great indicator of the openness of Egyptian society to allowing an increased female role in the political sphere in Egypt. It bodes well not only the possible thousands of women hoping to have a seat in the upcoming parliament, but to women in general who wish to have a decisive role in government.

However, it is easy for people – especially men – to claim that they are open to the possibility but when it comes to actually applying it, what is Egypt doing to ensure women have a defining part to play in politics?

In order to truly accept women as having a pivotal role in politics, we must first give them the respect they deserve. This, of course, starts with decreasing the alarming amount of sexual harassments. According to the Egypt Human Development Report in 2010, over 50% of women who responded admitted to being subject to sexual harassment by strangers in public transport, in the streets or by colleagues at work. This has overwhelmingly doubled to virtually all women in Egypt stating that they have experienced some sort of sexual harassment according to a 2013 UN study.

The problem is that some men don’t realize that what they’re doing actually constitutes as sexual harassment. They see joking about a woman’s clothing, way of speaking or features as normal – whereas to the woman, it can be deeply bothersome and hurtful.

There were, however, many movements instigated by Egyptians to decrease the number of sexual harassments. One of those was Operation Anti Sexual Harassment who were first known for intervening and preventing sexual assaults in Tahrir during protests and then expanded beyond Tahrir to the streets of Cairo. Their aim is to publicly raise awareness and to patrol the various streets of the capital and other cities, also passing out hotline numbers for sexual harassment complaint.

There is obviously so much they can do, which is why in 2014, the government issued a sexual harassment law based on articles 306 (a) and 306 (b) of the Penal Code. The law states that any verbal, behavioral, phone and online sexual harassment will result in the person accused serving a prison sentence of 6 months to 5 years and up to 50,000 L.E in fines.

This hasn’t definitively decreased the number of complaints however. In 2015, many women in Egypt still felt they were not protected; women on Twitter instigated hashtags to raise awareness asking people to describe and publish stories and photos of sexual harassers to speed up their arrest.

Last December, a woman jumped into the Nile from Qasr El Nil Bridge and drowned escaping her harasser who was belligerently following her. He threatened to throw nitric acid on her. It is very encouraging though that the government is not standing idle and that it is actively pursuing to limit sexual harassments in Egypt through passing laws as the one passed last year. Hopefully in the near future, we will see sterner laws being issued to definitively decrease this problem.

Women must first feel protected in the streets and in their households in order to even contemplate holding a place in government or parliament. They need to have the confidence to campaign without fear of sexism, misogyny, assault and belittlement on every corner.

The majority of Egyptian men say that they wouldn’t mind an Egyptian woman in parliament but when it comes to analyzing the political participation of women, the numbers are disappointingly low.

In parliaments, women have rarely had a role in parliament that wasn’t enforced by the government. In Mubarak’s parliaments, there was always an allocation for minorities and women. In the last Mubarak parliament, women held 12% of seats – the highest ever in Egyptian history. But there were questions whether those numbers actually gave an accurate representation of women’s role in political sphere.

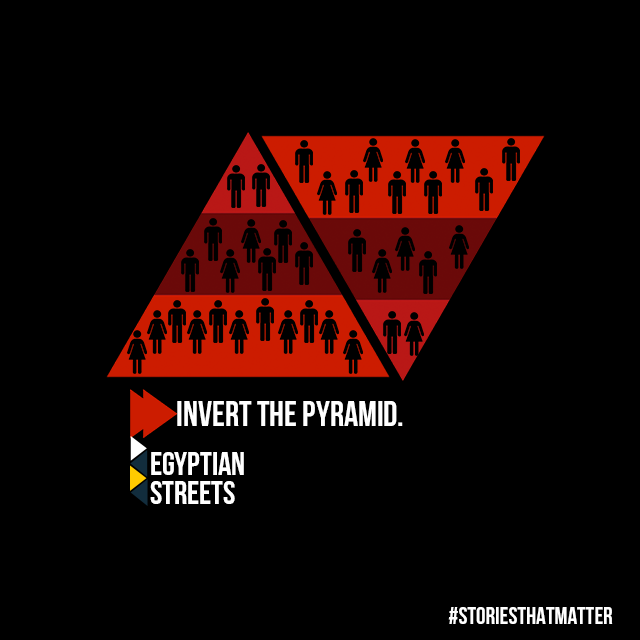

The government allocated seats for minorities in Egypt – which is absurd that women were considered a minority in the first place. In a country where women constitute over 49% of the general population, calling them a minority is representative of deeper lying issues. It’s representative of just how challenging it is for a woman to gain a foothold without the assistance of the government. The difficulty of this was proven in the 2011 parliament where the enforced quota was removed. As a result, the participation of women was a measly 2%.

This raises questions whether the upcoming parliament will issue quotas for women to ensure higher numbers and whether this really does anything for women at all. The fact that they need governmental assistance to be in parliament highlights just how tough it is for a woman to gather donations for her campaign, convince voters in their precincts and gain votes in a political community that is dominated by men and voters that categorically prefer a man as their representative.

In my opinion, the positive stance of men towards an increased role of in politics isn’t an indicator of openness, but an indicator of the dominant attitude men have over women. It’s easy to say one thing, but do another.

This is not just an event in Egypt, but a global phenomenon. Women have always been allocated under gender roles that have seen them marginalized in politics. Bar a few countries, most of the world’s leaders, government cabinets, parliaments are dominated by men leaving very little to women. It’s a profession that is unfortunately universally seen as masculine.

Men say that they would like for women to have a decisive role but based on previous elections – the last one just two years ago – is it really possible for women to gain an advantage without the government helping them? And if the government does help, is that not an indication of anything but the vulnerability of women in their struggle for political representation?

The government has taken the encouraging first step of that through the sexual harassment law and we will hopefully see more of these in the future. There needs to be more openness to allowing women in parliament and government – not just through opinion polls but the actual manifestation of those opinions in the ballot box, one without the help of the government. An encouraging note is Hala Shukrallah – who became the first Egyptian Coptic woman to head a political party in Egypt – the Dostour Party.

It is undeniable that women became more vocal after the revolution about the need for a more significant role for women in politics but in terms of ideological change in the minds of Egyptian, we see very little of that.

Edited by Marina Kilada and Enas El Masry

Comments (0)