Just before 11:30 A.M. on a warm spring day in late March (26th), train service 89 travelling from Luxor to Alexandria came to a standstill outside the town of Tahta, in the Sohag governorate in Upper Egypt. It was an unexplained stop, but one familiar to regular users of Egypt’s national rail system.

The crowded train sat for fifteen minutes in the heat. Then at 11:42 A.M. another train, service 2011, collided at speed into its back. Seventy-two ambulances were sent; 19 people ultimately died and 165 were injured. An investigation was announced, and the story made headlines across the world. On Twitter, President El Sisi wrote “The pain in our hearts today will only increase our determination to put an end to this type of disaster.”

تابعت عن كثب الحادث الأليم الذي شاهدناه اليوم بتصادم قطارين في محافظة سوهاج.

إن الألم الذي يعتصر قلوبنا اليوم، لن يزيدنا إلا إصرارا على إنهاء مثل هذا النمط من الكوارث

١/٣— Abdelfattah Elsisi (@AlsisiOfficial) March 26, 2021

Three weeks later, train 949 travelling from Cairo to Mansoura, derailed outside of Toukh, twenty miles north of Cairo, killing 23 people and injuring almost 140.

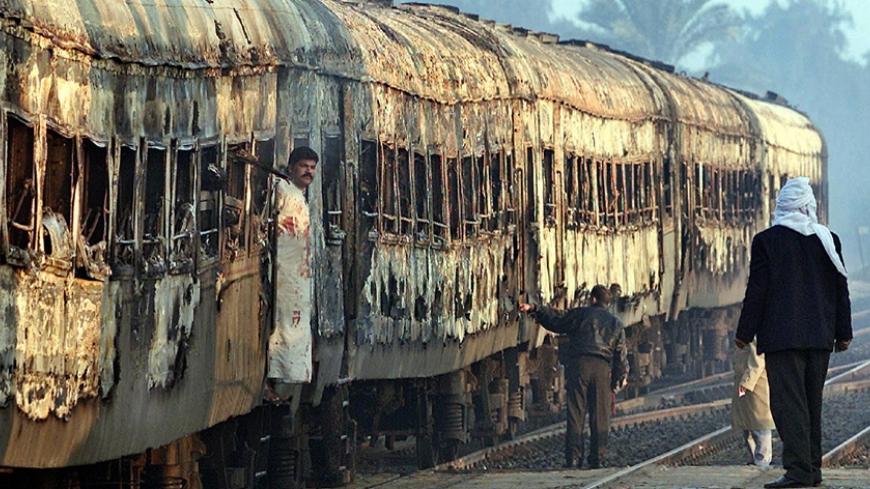

The Egyptian Railway Network has been hampered by safety concerns for some years now. Since 2000, over 700 people have died in train crashes in Egypt, more than 380 of them in 2002, when a sleeper train caught fire outside of Cairo. While there has been a complex and continuous blame game, little has been done to actually remedy Egypt’s behemoth of a railway network.

The oldest network in the Middle East

Egypt lays claim to one of the world’s oldest rail networks; construction started in 1848 with concessions to the British. The original rail network from Cairo to Alexandria was designed by British Engineer Robert Stevenson, with the first stretch completed in 1856, between Alexandria and Cairo. Under British and French control, the network expanded hugely in the latter half of the 19th century, largely at Egypt’s expense, according to historian Hugh Hughs.

It is now the biggest railway network in the Middle East and Africa. While it plays an important role in freight transportation, carrying over six million tonnes of goods each year, 90 percent of its work is carrying over 1.4 million passengers each day in a rolling stock of 35,000 cars.

Although the network has not been expanded since the occupation, it still serves as an economic and social lifeline that manages to reach a large proportion of the population. With tickets majorly subsidised by the government, it remains one of the most popular forms of transport in the country. The Institute for Developing Economies in Japan described it as playing “a significant role in the Egyptian economy.”

Yet, since its inception, the railways have been a financial burden. The entire system was built on debt to the European powers, and more than a century and a half later, the system remains in a financial ‘black hole’.

Ailing structure and infrastructure

As of 2020, Egyptian National Railways (ENR) was over EGP 250 billion in debt, both to the Central Bank of Egypt and in government loans. It was only last year that the government met to discuss a financial solution.

However, the adage ‘safety first’ may precede the financial issues faced by the organisation. ENR has one of the worst safety records for a railway of its size: in 2019, Germany had the worst rate of rail accidents in Europe with 298, according to Statistica. The previous year, the last year we have records for, Egypt recorded 2044.

As The Economist explains, the accidents’ repeated occurrences are due to a combination of outdated cars (the average age being 30 now), a lack of basic equipment training, and, perhaps most worryingly, rampant drug use amongst rail workers. Many of the network’s rails and signals have also not been renewed in decades, making it unstable and dangerous.

The task of tackling these monumental challenges is likely to require a combination of changes in policy and significant investment. However, many other countries have decided that prioritising a well-connected and well-maintained rail network has benefits that, down the line, outweigh the initial costs.

Stronger railway systems generally aid building strong economies. US President Joe Biden has made trains a part of his infrastructure plan, and in the UK, over GBP 100 billion is being spent on a controversial new high-speed rail link.

The road ahead

Egypt is looking to expand its network with projects for the 2030 Vision Plan. In January 2021, the government signed a major deal worth $23 billion with the German manufacturer Siemens for a new electric high speed line between the North Coast, the New Capital, and the East Coast, running from El Alamein through to Ain Sokhna, in a project that President El Sisi hailed as a “significant addition to the country’s transport network in terms of trade and passenger transport.”

Construction is also underway on a light-railway connecting Cairo with the New Capital and 6th October City after a deal with China Railway Group Ltd in 2017. Yet these projects could be seen as being built by foreign companies to serve the rich and foreigners without addressing the major problems that the majority of the population face day-to-day on the crumbling old system.

Yet, in late spring of 2021, it was announced that money was finally coming in to aid the pre-existing railway system as well. This money was not through agreements with foreign companies but loans from the African Development Bank and the Bank for Reconstruction and Development (part of the World Bank) totalling $540 million.

To put this in perspective, the UK spent $22.5 billion on its privatised rail network last year. Although the British rail network is about three times longer than its Egyptian counterpart, there is still a significant disparity in overall expenditure. However, this money could still benefit in terms of the old network’s renovation.

Egypt also has an example of effective mass transit hiding in plain sight in the very heart of the country: the Cairo metro system. Built in the 1980s, the network is yet to record a major accident, this despite carrying almost 1.3 billion passengers each year, the same level as the much longer and older London Underground system; and more than twice the total number of passengers on Egypt’s entire railway system.

Down in the Sohag governorate, as the camera crews move on to the next story and the dust settles from the crash in March, citizens are going about their daily lives. While a commission was set up to determine what went wrong on March 26, and money has been allocated to the families of the victims, people are still questioning what actually happened and why; and wondering when the next deadly accident may occur.

A video of a man inside one of the crumpled carriages circulated online after the accident in Tahta and was picked up by CNN. “Where is the help?” He screams, “people are dying here.”

Comments (4)

[…] Legu la kompletan artikolon en la originala lingvo : English […]

[…] End of Line: Egypt Struggles with Crumbling Rail System “Pervert from Cairo airport” got into criminal case […]