On the morning of Wednesday 1 July 2020, posts started appearing on social media accusing an Egyptian man in his twenties of rape, sexual assault and sexual harassment. By nighttime, that man had been accused by more than 50 Egyptian and foreign women of numerous sexual crimes, the failures of institutions were exposed and two hashtags related to the allegations were the top trending in Egypt.

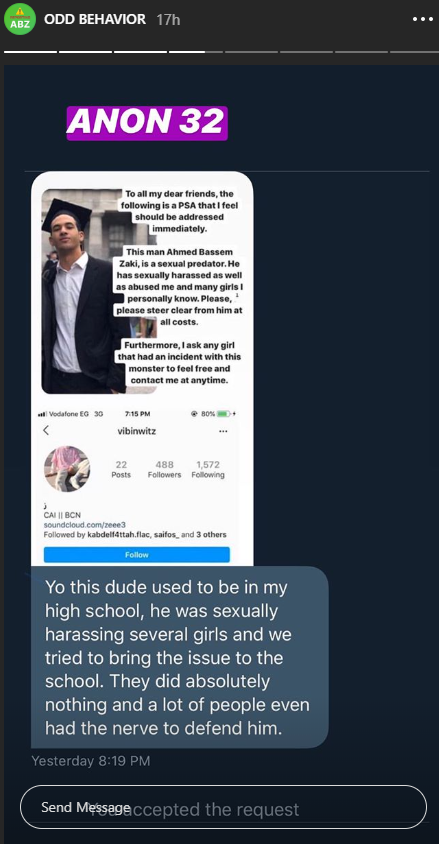

The allegations against Ahmed Bassam Zaki, an Egyptian who graduated from high-school in Cairo in 2016, were first shared by a female American University in Cairo (AUC) student in 2018. The woman, whose name Egyptian Streets has chosen not to disclose for her safety and privacy, accused Zaki of harassing her and her friends, posting an account of her experiences on the Facebook group “RATE AUC PROFESSORS”, a group that is not officially associated with the AUC or its administration.

The post on RATE AUC PROFESSORS attracted thousands of comments before suddenly being deleted by administrators of the group earlier this week – two years later.

Within the hours after the post’s deletion, dozens of women started coming forward, with their stories and experiences shared by two key profiles on Instagram that resulted in widespread attention: @skhodirr (writer and poet Sabah Khodir’s personal profile) and @assaultpolice.

His name, Ahmed Zaki, and #المتحرش_احمد_بسام_زكي (The Rapist Ahmed Bassam Zaki) remain trending on Twitter as at the date and time of publication, with stories and a petition being shared around.

What horrified many in Egypt and contributed to the wildfire spread of allegations against Zaki was the fact that these allegations dated back many years to at least as early as 2016 when Zaki was in high school.

TRIGGER WARNING: This article contains graphic details of incidents of rape and sexual attack. This article also includes language that may not be suitable for children. Reader discretion is advised.

The Beginning

According to information that has been made available online and to Egyptian Streets, the first public allegations against Zaki were made in 2016, when Zaki was a senior at the American International School (AIS) in Cairo, a school he had attended between 2015 and 2016 before his graduating and commencing studies at AUC.

There were several claims of Zaki making multiple social media accounts to privately message girls, repeatedly asking for their numbers and for inappropriate favours.

View this post on Instagram

Sources speaking to Egyptian Streets have confirmed AIS administration’s awareness of the allegations against Zaki. Despite investigating and verifying the claims, Egyptian Streets understands AIS chose to take no punitive action against Zaki as he was only days from graduation. Instead, Zaki was merely spoken to and given a warning, while girls at AIS were warned of the dangers of social media and sending photos of themselves and engaging in sexual contact. Many ex-students have spoken about USBs and folders containing private photos of girls being shared around (by those other than Zaki) and blackmailed for years to follow, also without any repercussion against the perpetrators.

The lack of more punitive action has been highlighted by social media users in Egypt, many of whom have sent messages and emails to AIS demanding an explanation. According to information received by Egyptian Streets, staff at AIS admitted their failure, recognising that in hindsight, these actions were not enough.

Meanwhile, posts dated May 2016 on a private Facebook group created by AIS Class of 2016 students showed a number of Zaki’s classmates posting messages of support and solidarity. Egyptian Streets has chosen not to share these messages, which expressed support for Zaki.

Some of these classmates continued to support Zaki in messages seen by Egyptian Streets from an AIS Class of 2016 Whatsapp group. In these messages, which were sent yesterday, on Wednesday morning, when allegations against Zaki were made on social media, Zaki admitted to “having a problem” and that he is “getting help for it”, adding that he “never meant to hurt anyone”. Classmates, including both men and women, on the Whatsapp group responded with various messages of support, including asking how they can help him. As more stories came out against him, many classmates changed their perspective, expressing fear, disgust, and disbelief.

While this response may seem surprising, it has been the case for years – students dominating the group chat in defense of Zaki’s mental health and to not ruin his reputation. The way Zaki’s alleged actions were swiftly moved past is reflective of the culture which does not work in favor of victims, instead leaving them unsupported and feeling shame.

Blackmail and Assault

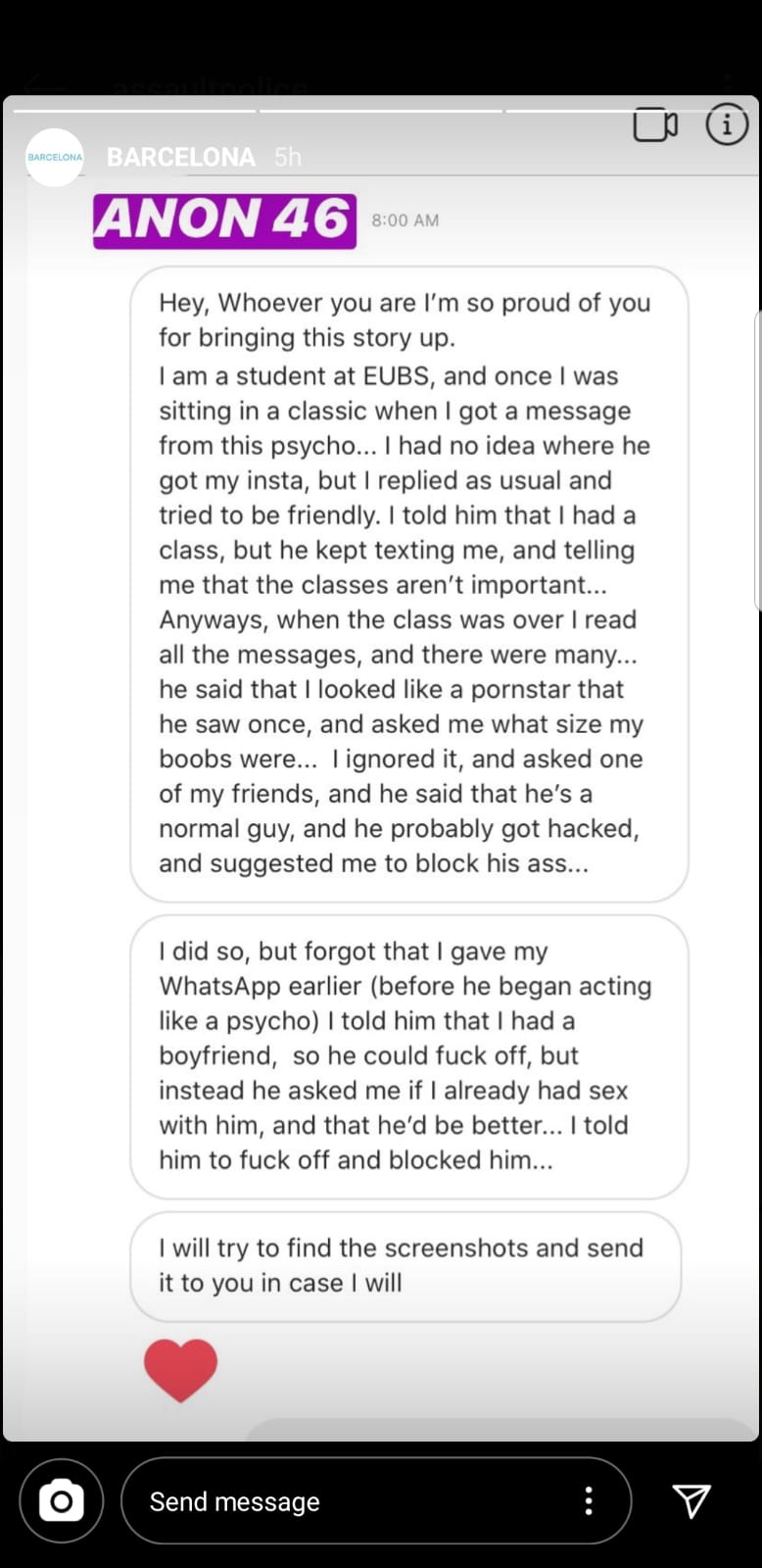

The bulk of allegations against Zaki relate to incidents of rape, sexual assault and sexual harassment that allegedly took place during his studies at AUC, between 2016 and 2018, and his further studies at the EU Business School Barcelona since 2018, which confirmed on Wednesday night that it had suspended Zaki’s enrollment pending further investigations.

Zaki has been accused of using various tactics to lure his victims or to otherwise force them to act against their will.

One widely shared, and graphic, account was posted by @assaultpolice (an account dedicated to compiling evidence against Zaki) on Wednesday evening and details Zaki luring his victim to meet him under the pretense that it was a gathering with a larger friendship group of his: [Trigger warning – text in italics is graphic]

“This person has convinced me to go to a meeting with his friends called chillawy group. Then when I got there he said the group couldn’t come for some reason.

From the minute I was there he kept flirting with me although I said it didn’t make me comfortable. He kept seuxalizing my lips and my eyes. My favourite features of myself that stopped being my favorite as soon as those words left his mouth.

He kept finding excuses to touch me, although every time he did, I’d say I’m not comfortable with excess touchiness. He got angry and he said I was a prude, that I should be open minded…

Then he started asking me to kiss him, going back to the same flirting. I kept saying no. I didn’t want to. I had just had a bad breakup a couple of days ago, and something about this uncomfortableness broke me. I started crying. Instead of trying to see what’s wrong, he kisses me. We were alone in a compound and I was honestly scared for my life. I didn’t know what to do. I let him kiss me and continued crying. It didn’t stop there.

I was breaking down and crying, and he was making his way down my pants. I kept saying no and I tried to get out of his grasp, but I couldn’t. He fingered me. I bled. I cried louder. In my head I couldn’t believe it was happening. I didn’t think it was true.

I managed to push him and I told him off, he said he wants to continue until he comes so that he ‘doesn’t get blue balls’ and asked me – the f*****g audacity – to just stand still so that he could think about me while he masturbates.”

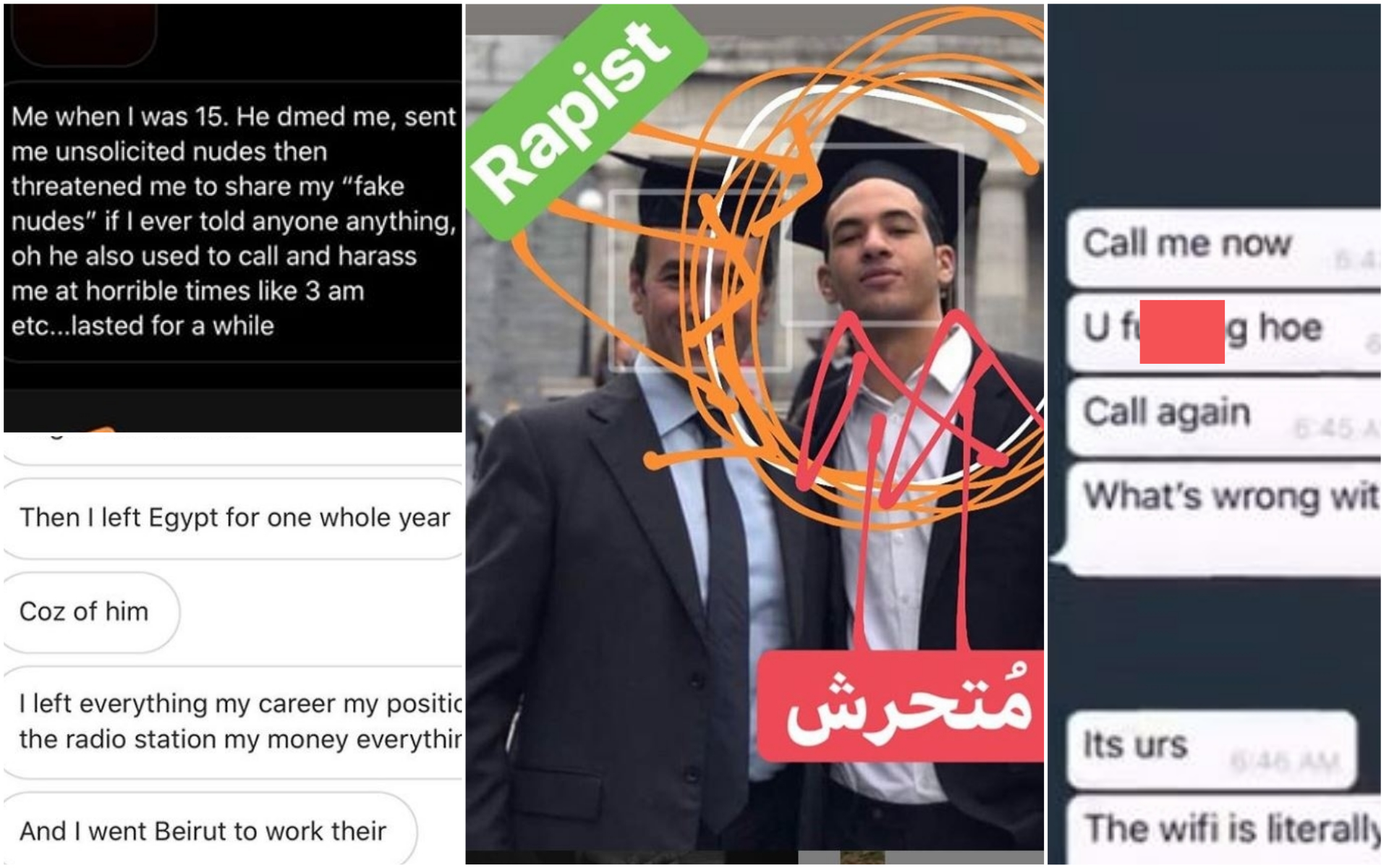

The account of the sexual assault continues, revealing that Zaki “contacted me again saying he had a video of the ‘makeout’ as he called it and that he wants to see me again”. Zaki allegedly continued blackmailing her for days.

The allegations of Zaki using blackmail have been corroborated by a number of other women sharing their experiences.

Voice recordings shared by one woman to @assaultpolice allegedly capture Zaki threatening to “go straight to her sister”: [Trigger warning – text in italics is graphic]

“If you didn’t answer this phone call I would’ve gone [sic] straight to your sister, be like, ‘yo, khaleeha tekalemni’ (let her call me), and if you don’t, I’ll be sending her shit 3alatool (right away). Like yo, take this.

I know I’m such a bitch. But you’re a whore. And you’re gonna get down on your knees and suck my c**k for me to shut up about it. So, are you gonna suck my c**k or should I tell your sister.

Alright, so think about it. Do you wanna be a sl*t again, or do you wanna be a f*****g outlaw? Think about coming.

Think about the whole proposition that I have for you. Right now it is 9:48. At 10:30, I want an answer. Peace?”

Numerous other women have claimed Zaki blackmailed them. This includes using both real and fake nudes of other people, with threats to share them with friends and family members, or otherwise threatening to tell family members stories of sexual contact.

Screenshots shared of separate conversations between a number of women and a person alleged to be Zaki show various threats and aggressive behavior.

“Call me now. U f*****g hoe,” reads one message allegedly from Zaki.

“Ana ghaltan en (I was wrong that) I didn’t tell ur sister.”

Zaki also allegedly used his mental state as a means of manipulation, threatening self-harm and suicide.

“You know what, let me send a broadcast to all my contacts, ill say ‘hey, i need you tonight, can u come to my compound and talk?’ And if any person whatsoever shows up i wont commit suicide, and if nobody at all shows up, ill do it tonight…deal?” writes a person alleged to be Zaki in one message.

“Why are you having these thoughts,” responds the woman, only to be shut down.

“STOP. I DONT WANNA TALK ABOUT IT. I JUST WANNA F**K YOU AND LEAVE. Do u finally understand that?”

Dozens of other similar stories and accounts have been shared by women in Egypt and in Spain, where Zaki is enrolled at EU Business School Barcelona.

These stories range from accounts of rape, sexual assault and sexual harassment, to instances of unwanted and uncomfortable advances and messages allegedly received from Zaki. Those Zaki allegedly assaulted or harassed range from girls under the age of 18 to women in their early and mid-twenties in Egypt and abroad.

As at the date of publication, Zaki has not publicly commented about the allegations made against him.

Blaming Women and Purity

The response to the dozens of allegations made against Zaki has, overwhelmingly, been in support of the victims. However, social media often does not reflect real life and certain segments of society.

Alleged threats by Zaki against various women to share fake nudes, messages or encounters with their family members and friends reveals the complex way in which rape and sexual behaviour are viewed in Egypt.

One account shared by a woman to @assaultpolice details how after allegedly being raped by Zaki when she was 19-years-old, she was dismissed by her mother and forced to move to another country, abandoning her family, friends and life: [Trigger warning – text in italics is graphic]

“So I was 19 and he was 20 and the dumbass naive me fell in love with him…

I was attached to him. He kept telling me personal things and he was sharing things with me I thought I was special so I did the same things and told him things I shouldn’t…

One day I was at a friend’s house…he called me told me to send him the location he will pick me up because he needs someone to talk to and he sounded like he was crying so of course I did what he asked.

Then he took me to his compound. I thought maybe we will just hang there like usual but he drove me to his house I asked him what are we doing here he said the house is empty only the maid is there and I can [sic] still hear his voice telling me ‘don’t worry princess, I won’t lay a hand on you’. I trusted him and went inside. He then started talking about an issue he been having and then he leaned in and kissed me, I kissed him back. He held me and took me to his room. I was really not thinking I was in love.

When I realized that we’re in his room I panicked and started breathing really hard and I told him I need to leave and managed to get out of his room. He grabbed my hair and threw me on the floor. He unbuttoned my pants and I was shaking and crying and I always get panic attacks. I tried to scream but nothing came out.

When he took what he wanted I saw blood on my clothes I panicked and all he had to say ‘go to your uncle now sl*t. You’re not different than the other girls. Whore. Sl*t’. I left and I called my mom, I told her everything.

She didn’t do anything. He then kept calling me and sending me messages, asking for a round 2 or else he would tell my family. I told him go for it. My mom knows.

He read the messages. Then my mom took my phone, laptop, made me delete all my social media accounts. And she made me move [location abroad] and now I’m all alone, without a family, my friends are mad at me because after the accident I pushed everyone away.

I see him everytime I look at myself in the mirror.”

Solidarity with Zaki among his AIS classmates in 2016 also reveals the pressures girls and women face when they go public with their experiences. Sabah Khodir, whose posts on her personal Instagram sparked stories related to Zaki being widely shared by tens of thousands of social media users, received a number of hateful messages and comments from various individuals.

“Look at what you’re wearing and you don’t want someone to come rape you?” read one message Khodir received on Instagram.

In statements to Egyptian Streets, Khodir said she expected to receive such hateful messages when her post started going viral.

“Once my post began receiving viral attention, my first instinct was to go on my Instagram and begin removing pictures of myself that may show any amount of skin that I know may be used to manipulate my image as a distraction to the case,” says Khodir to Egyptian Streets.

“I did not want anyone to take a picture of mine with my arms showing and to then say ‘of course! whores always stand up for whores!” which I have heard. And beyond my best efforts, I have still received comments and messages from men continuing to curse at me and call me a whore for spreading awareness,” continues Khodir.

“Which further proved my assumption that men like them and Ahmed Zaki have one thing in common: they think calling a girl a whore is the best way to scare her into doing what they want.”

The messages are similar to those seen in comments across social media after 17-year-old Menna Abdel Aziz shared a live Facebook video accusing a male friend of rape.

Abdel Aziz, whose rape was confirmed by police investigators, was arrested for “misusing social media networks, inciting debauchery and violating Egyptian family values” after her social media posts, which often showed her dancing and singing, went viral when she accused her friend of rape. A number of social media users, including the perpetrator Mazen Ibrahem, shared photos of Abdel Aziz deemed by those users as overtly sexual or inappropriate, with some commenting that she was ‘asking for it’.

“How could I rape her?” commented Ibrahem on one now-deleted photo on Facebook that showed Menna sitting on his lap.

Similarly, in 2018, an Egyptian woman released a video of a man who sexually harassed her in broad daylight in Cairo’s Fifth Settlement. The man had circled the woman with his car three times, making remarks that made her feel uncomfortable. He eventually parked his car near her and approached her, asking if she wanted to grab a coffee with him.

The sexual harassment incident, which ended up becoming the “Teegy neshrab coffee?” (let’s drink coffee?) meme, saw the woman delete her Facebook account after she was the subject of waves of abuse from other social media users. This included her private photos being shared by some who questioned whether what she was wearing could have “invited” the man’s advances.

While the woman was forced to disappear from public life in the aftermath of her video’s release, the man was turned into a meme and even praised by some. Photos from social media at the time even showed a night club in Egypt remixing the video, with the man attending the event and taking photos with attendees. Meanwhile, Dunkin’ Donut posted a photograph on Facebook alluding to the incident with the caption “Teegy neshrab coffee at DD?” (‘Let’s drink coffee at DD?’) to promote its brand.

While there has been significant movement since 2011 by authorities against sexual harassment, with stricter laws and punishment being introduced, it remains particularly difficult for women to publicly accuse men of rape, sexual assault or sexual harassment due to social and cultural views around sex and sexuality.

Equally troubling is the fact that premarital sexual contact continues to be widely frowned upon in public circles in Egypt and notions of purity are imposed on women and girls from a young age. Egyptian women are taught that sex and shame come hand in hand. The issue that arises here, is that when they are victims of assault or harassment, the shame and blame is still pointed towards them.

Purity culture, as explained by Egyptian feminist and activist, Mona El-Tahawy, is a “rhetoric that stresses virginity and modest as the way for women to attain ‘purity’”. This culture exists everywhere in Egypt, whether it’s in the home, public spaces, or institutions. The issue that emerges from purity culture is that it leaves women burdened with the responsibility of their own safety from sexual violence, that is, by ensuring they don’t “tempt” boys and men.

While this idea exists beyond Egypt, the rhetoric is especially present in the region as can be seen through the fact that many victims felt they couldn’t speak out for fear of being exiled or shamed by the community. Purity culture also manifests when we hear women being asked, “What were you wearing?” or “Why were you there in the first place?”.

Not only does it not matter what they were wearing, or why they were there as assault can happen to anyone in any situation, it is also unacceptable to discredit women’s assault based on their existing sexual history. This attitude contributes to rape culture by placing the blame on victims, rather than holding perpetrators accountable.

Power of Social Media

While social media can be used for nefarious purposes, including lately as evidence to arrest girls and women for posting videos on TikTok deemed to be against the morals of public society, the spread of allegations against Zaki show how it can also be used to facilitate justice.

Despite being accused of “asking for it” and being arrested for “debauchery” and “violation of public morals”, Abdel Aziz’s case also revealed the role social media backlash can play in achieving justice.

Prior to being arrested, and after her first video accusing Ibrahem of rape, Abdel Aziz released a follow up video seemingly denying that she was raped. With a man apparently directing her off camera, Abdel Aziz said “there was no rape”, that she was simply “beaten up” and that Ibrahem “is like an older brother”. Social media users were quick to question whether Abdel Aziz was forced to make the follow up video and a hashtag calling for justice for Abdel Aziz became the top trending hashtag in Egypt, with newspapers across the country reporting on it.

Within 24 hours, Ibrahem was arrested and police confirmed that investigations had revealed Abdel Aziz was indeed raped.

Meanwhile, earlier in June 2020, two other men were accused of sexual assault and harassment on social media by a number of women. The two men, Mohanad Ibrahim and a colleague of his whose name Egyptian Streets has chosen not to report pending further investigations, were both members of the student-run International Student Leadership Conference (ISLC). ISLC is a student club hosted by AUC that is open to other universities and is not managed, run or operated by AUC’s administration (Mohanad is not a student at AUC).

This is another victim of Mohanad’s. She does not wish to be named so do not ask me for her name.

يا رب يا مهند يا خول اللي عملته في كل البنات دي يطلع عليك بلى أزرق، يا رب تتعذب دنيا و آخرة و تفضل حاسس بوساختك كدة.@knowyatt عشان بس تشوف قذارتك و وساختك، أنت شخص مقرف ميستاهلش أي- pic.twitter.com/xq22zDb8hS— Hannah | blm (@hellishhan) June 23, 2020

After a couple accusations started spreading on social media, more women were emboldened to share their experiences of alleged sexual assault and sexual harassment experiences at the hands of Ibrahim and his colleague.

One account shared by a woman alleged that Ibrahim had told her he had raped someone in the past. Ibrahim, who had cultivated a social presence both virtually and among ISLC’s members as a progressive feminist, is alleged to have used this same reputation and presence to gaslight and invalidate the claims of women accusing him.

As the number of claims increased, Ibrahim rescinded his denials and tweeted an apology (which did not contain an explicit confession but alluded to the claims), before deactivating his Twitter account. Ibrahim was also fired from his job.

Events like this mirror many others around the world, where the platform and anonymity offered by social media emboldens women who may otherwise have been too intimidated or afraid of potential harm coming to them, to come forward.

Finding solidarity through social media, though certainly not limited to cases of sexual assault or rape, was a key driver behind the #MeToo movement, which did not gain as much traction in Egypt but set a precedent for using social media to expose the sexual misconduct of men in positions of power.

What remains to be seen is whether there will be a shift in culture in Egypt, where men who are accused of rape, sexual assault or other sexual misconduct on social media, will be held accountable under the courts of law and not just the court of public opinion.

Though Menna Abdel Aziz’s case shows that this is possible, and that police will act in some cases, it is arguable that this case was unique and linked more so to violation of public morals and family values through videos that had been shared, and later came to light, by Abdel Aziz and her rapist.

Amr Warda, an Egyptian footballer, was accused during the African Cup of Nations of sexual harassment. The sexual harassment claims against Warda were first sparked by Egyptian-British model Merhan Keller, who alleged that Warda had sent her inappropriate and aggressive messages.

Keller followed up on her claims by later sharing testimonies of a number of other women who contacted her saying they had received unwanted and inappropriate messages from the Egyptian footballer.

On Twitter, screenshots of messages and videos allegedly sent by Warda to women on Instagram spread quickly. Dozens of women claimed to have been victims of Warda’s cyber sexual harassment, with some messages allegedly showing Warda becoming aggressive when rejected by women.

Though Warda was initially, and swiftly, dismissed from the Egyptian national football team by the Egyptian Football Association (EFA), support from Warda’s teammates contributed to the EFA’s decision to reinstate Warda just days after his initial dismissal.

Meanwhile, no legal action was ever taken against Warda, despite his unwanted messages and cyber sexual harassment being a crime under Egyptian law.

There remains hope among social media users that Zaki and other men recently accused of sexual misconduct will be properly investigated by authorities. Whether such hope will amount to more is yet to be determined, and for many, Egypt’s recent history of dealing with sexual crimes exposed on social media does not provide much comfort.

[Update at 5:21PM Cairo Time: Shortly after the publication of this article, the National Council for Women released a statement regarding the allegations against Zaki.]

Egypt’s National Council for Women (NCW), presided by Dr. Maya Morsy, released a statement in Arabic on Thursday afternoon stating that the NCW is “monitoring closely and with great interest, the issue currently discussed on social media”. The statement recognises that evidence has been collected against Zaki and calls on all relevant authorities to investigate and take necessary measures.

The NCW also called on women to file official complaints against Zaki “so that he gets the punishment he deserves as per the law and becomes an example for whomever touches or harasses girls”.

Comments (65)

[…] is the best tl;dr I could make, original reduced by 97%. (I’m a […]

[…] is the best tl;dr I could make, original reduced by 97%. (I’m a […]